Contents

I struggled to come up with a title for this piece. The use of the term “kitchen gardens”, which implies growing for self-consumption, seemed obvious at first. However, as you will see from the following content list, I have included some areas that could arguably not be described as such, notably market gardens. “Common Ground: A Potted History of Productive Gardens” might perhaps have been a more appropriate title?

Dates. Please note that BCE (Before the Common Era) and CE (Common Era) are used in this piece, as opposed to BC and AD.

- In the Beginning

- Ancient Egypt

- The Roman Period

- The Open Field System

- Monasticism

- Market Gardens

- Walled Kitchen Gardens

- Allotments

- Appendix – Origins of Selected Vegetables

- Bibliography & Further Reading

- Acknowledgements

- Version History

In the Beginning

The Fertile Crescent in the Middle East is considered to have been the area where agriculture in Europe and the Near East began, somewhere around 9,000 BCE.

Horticulture originally developed in Egypt around 2000 BCE, and by 1500 BCE there is evidence of roses, lily of the valley, saffron, apples, dates, pomegranates, cucumbers, melons, gourds, onion and garlic plus various herbs and spices. Pears and nuts subsequently appeared in Persia around 500 BCE, while cabbage, asparagus, seakale, iris and narcissus are thought to be attributable to the Ancient Greeks around the same period.

Ancient Egypt

The River Nile and the connected canals provided the water that was necessary for successful cultivation. Initially, cultivation beds were encased in earthen walls which allowed the water to soak through.

Perhaps we can consider three broad categories of usage: temples, the affluent and tenant-farmers.

Medium to large temples had significant numbers of priests and supporting staff with the attendant need to feed them. The Temple of Amun-Re at Karnak had 26 kitchen gardens and a very early botanical garden, plus rows of trees such as fig sycamores along adjoining paths which helped to provide some shade. Meanwhile, the rich had their own kitchen gardens, albeit on a smaller scale, some of them walled.

Vegetables that were grown included onions, leeks, lentils, lettuce and cucumber; coriander and cumin; a range of herbs; along with fig, date, carob, tamarisk and other trees.

There were many tenant-farms that varied in size from small holdings where the emphasis was on feeding a farmer’s own family to larger holdings where the excess was sold. Cereal crops formed the major product.

The Roman Period

The Romans supplemented their native cultivation expertise by assimilating knowledge from peoples in various parts of their empire, principally in the eastern Mediterranean and the near Middle East where the longest pedigree was to be found.

Their experience led to works on cultivation that were written at various times, notably by Cato the Elder (2nd century BCE), Varro (1st century BCE), along with Columella and Pliny the Elder (both in the 1st century CE). The most comprehensive of these agricultural manuals was written by Columella, a native of a municipium in southern Spain (present-day Cádiz).

Cato the Elder described simple composting ideas in his work although the techniques were also known to the Ancient Chinese and the Greeks.

The Romans were also aware of forcing techniques. For example, the Emperor Tiberius was advised by his doctors to eat cucumbers every day. They were produced out of season by growing them in mobile containers of fermenting dung, covered with sheets of mica.

With respect to fruit, it is said that at the height of their power there were 22 varieties of apple, 36 of pear, 8 of cherry, 4 of peach, 3 of quince, many plums, medlars, grapes, olives and strawberries. With respect to vegetables, they grew carrot, parsnip, beet, chicory and mustard, while mushrooms were collected from the woods.

Archaeological evidence of kitchen gardens at the residences of the affluent has been found at Pompeii, the earliest being at the House of Pansa where there was a large garden with rectangular plots separated by paths which also acted as irrigation channels. Two kitchen gardens have also been found at Settefinestre (north of Rome).

In addition, various sites around the provinces suggest the probable presence of kitchen gardens at villas in places such as the Lower Rhine in Germany, Southern England and Voerendaal in the Netherlands, along with a corridor house at Carnuntum in modern Austria..

On a smaller scale, evidence has been found that Roman soldiers grew vegetables in modest gardens at Wallsend and Housesteads on Hadrian’s Wall, and at Croy Hill and Rough Castle on the Antonine Wall. These gardens were small irregular plots which were located outside the walls of the forts.

The Open Field System

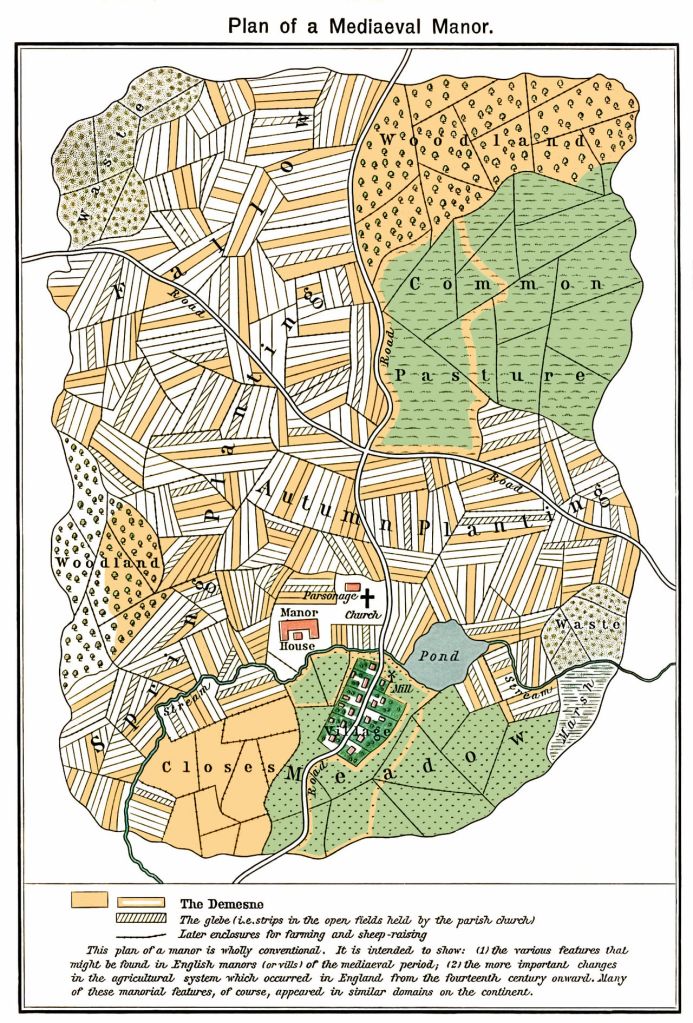

The rich naturally continued to produce their own food after the fall of the Western Roman Empire. However, the Open Field System gradually became popular in North Western Europe, including parts of England, from the 8th and 9th centuries to cater for the poor.

A village was surrounded by several large fields that were split into long narrow sections, typically one furlong (220 yards) by one chain (22 yards). The attraction of large fields was that it made ploughing easier when jointly undertaken. Heavy ploughs and largely clay-based soil made ploughing a difficult task for individuals on small pieces of land. Each furlong stretch was split into strips (called selions), typically of half an acre or less.

Each villager had a number of strips that were allocated to him at a public meeting at the start of the year. They were widely scattered to prevent one person getting all the good (or all the poor) land. Crop rotation was practised by field: a three-year rotation consisting of barley in one field in year 1, wheat in year 2, while it lay fallow in year 3. In addition to the “three” fields, there was common land for livestock to graze (fallow land and stubble were also used for this purpose) and common woodland for hunting and fuel collection. This system was evolved by communities who relied totally on the land, having few opportunities to barter and exchange. It slowly began to decline from the 15th century onwards.

Monasticism

During the Anglo-Saxon period when monasticism in Britain was in its infancy, it seems reasonable to assume that monks would have been largely responsible for working the land to feed themselves.

However, the situation changed from the Norman period when the number of monastic orders grew rapidly across Europe, resulting in a significant increase in the number of abbeys and monks. By the 13th century, rulers and the aristocracy had begun making bequests of land to abbeys, thinking that such gifts would smooth their eventual entry into Heaven. This produced a good number of wealthy abbeys with landowning running into thousands of acres. They were in essence businesses.

If we restrict the discussion to the Cistercian order which focused on self-sufficiency, it can be seen that the majority of hard agricultural work was carried out by conversi, lay brothers who had taken oaths of chastity, poverty and obedience. Mixed arable and pasture farms, often called granges, could be up to one day’s journey from an abbey.

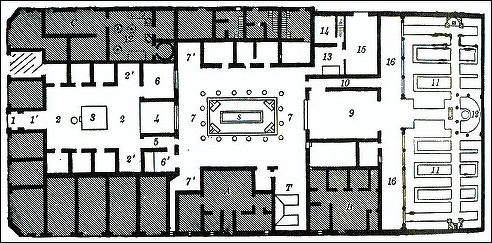

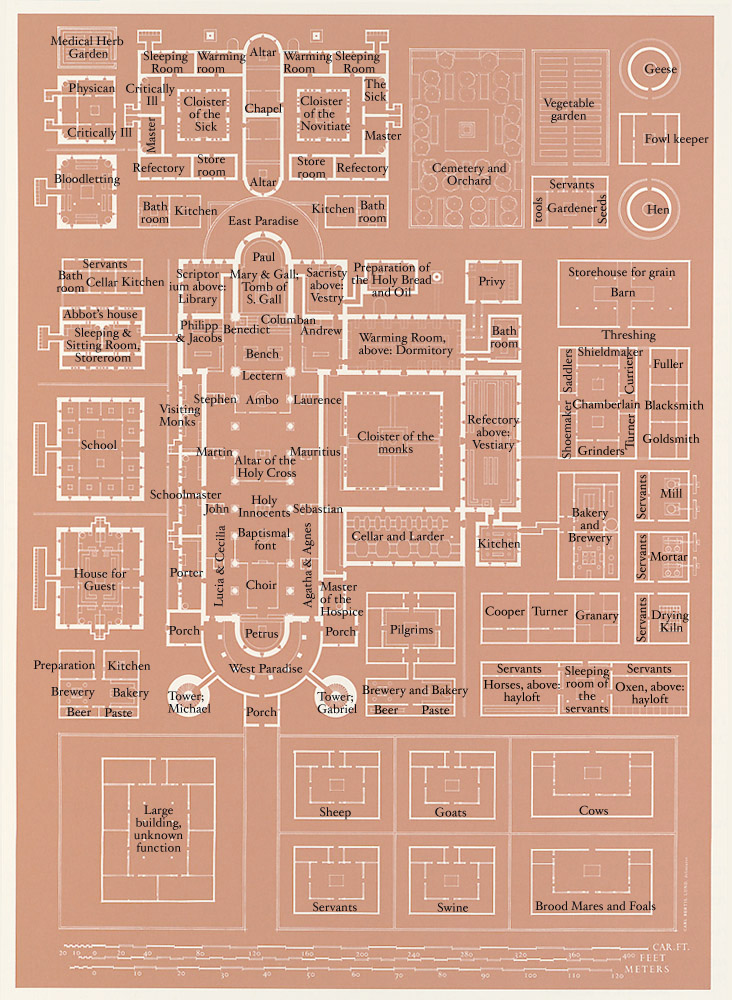

In this scenario, monks were typically limited to tending the herb, physic and fruit gardens that were sited with the grounds of the abbey itself. These gardens were based on classical designs, the concept of disparate gardens, and the beds within them, going back to ancient Egypt. Surviving documentation for the proposed Swiss Benedictine abbey of St. Gall in the 9th century describes three gardens: an orchard cum cemetery; a kitchen garden with 18 beds, each 20 feet long and 5 feet wide; and an infirmary garden with 16 beds, each half the size of the kitchen garden equivalent, which was used for growing culinary and medicinal herbs.

The appearance of the Black Death in the 14th century obviously had an adverse effect with the high death rate, possibly 35-40% of the entire population in England, resulting in severe labour shortages for abbeys and the need to sell some of the farms. And finally, the Dissolution of the Monasteries in the later reign of Henry VIII effectively saw the end of the monks and their need to grow food.

Market Gardens

Early markets were often used to sell surplus produce from the houses of the rich and from abbeys. In addition, there were some embryonic signs of individuals who grew fruit and vegetables for sale, subsequently to become known as market gardeners.

Increasing demand for vegetables by the 16th century led to the spread of markets and the beginnings of the market gardening business. Demand was in part stimulated among the poor by grain harvest failures, particularly those that occurred at the close of the 16th century (1595-1597), leading to the greater consumption of root crops. Meanwhile, at the top end of the market the growing popularity among the wealthy of French cuisine with its imaginative use of vegetables and a smaller emphasis on meat was an undoubted influence, leading market gardeners to seek to satisfy this taste.

There is significant information on the development of market gardening in the UK. London, unsurprisingly, was the initial centre of the trade in England, encouraged by immigrants from the Low Countries, particularly Holland, where market gardening was already well established. For example, the Dutch already had a thriving commercial root crop trade.

The Worshipful Company of Gardeners, a guild for those market gardeners who were operating within 6 miles of the City of London, received its royal charter in 1605. By 1649 a total of 1,500 labourers and 400 apprentices were employed within the guild, the average member of the company employing around six labourers plus one or two apprentices. The maximum permitted size of a member’s holding was 10 acres although some naturally circumvented this rule by acquiring additional holdings outside the area.

The City of London was surrounded by market gardens in the 17th century: in the west the alluvial soil around Chelsea, Fulham and Kensington was excellent for growing crops; while in the east, Hackney, Houndsditch and Mile End were established growing areas. Neat House Gardens in Pimlico was arguably the most famous area, eventually growing to 200 acres with a gross income of £200k per annum by the end of the 18th century. The area had been owned by the Abbots of Westminster until the Dissolution of the Monasteries in the 1530s.

The early market gardens were mostly congregated by the Thames where the best soil was to be found and transportation (by river) was easiest.

As development pressures increased, market gardeners were forced to move out to places such as Twickenham and Isleworth in the west, Plaistow and Barking in the east and the Lea Valley to the north.

Market gardens began to appear elsewhere across the country, in places such as Oxford, York, Bristol, Nottingham and Ipswich. The soil in the Evesham area (famous for asparagus) was exploited in the second half of the 17th century, followed by the Vale of Taunton Dean in Somerset, Exeter and Plymouth. Other market gardening areas included: places along the east coast where immigrants from the Low Countries settled, e.g. Sandwich, Norwich, Maidstone, Canterbury and Colchester.

In Scotland the Lothians was an important area with market gardens along the coast and by the side of rivers. The perennially popular leek variety, Musselburgh, was reputedly the result of crossing a cultivated leek from France or Holland with allium ampelsprasum which grew wild on the seashore near Musselburgh, just outside Edinburgh. Market gardeners were called mail gardeners in the Lothians because the produce went to Edinburgh and Glasgow by mail coach. By 1750 most large towns and quite a few smaller centres of population were being supplied.

A market garden was typically laid out in long narrow beds with paths between them. In fact, the paths, which were required to provide all year-round access to the beds, could take up as much as 20% of the land.

Walls were useful to retain heat, lessen wind damage and create a microclimate, although reed fence, plank fence or stout hedge could be used as alternatives.

Market gardeners needed lots of manure and fertiliser. They would take animal and human waste from nearby towns – London being the most obvious example where it was stored in laystalls at the edge of the city before being transported to the market gardens, often by barge. The manure was stored in heaps until fully rotted, although it was also used when fresh in hotbeds to produce a variety of early crops. Asparagus is a good example, although the plants would be spent after a single season.

Inter-cropping was a popular technique for making the best use of the available space. Here crops with different growing times would be sown or planted in the same bed; those crops with the shorter growing time, such as radish, could then be harvested, allowing the other crops, e.g. carrots or parsnips, more room and time to develop.

Great store was set by digging, 2 spades deep in winter. Further work was done in the spring to remove weeds and “open up the soil”. The soil was dug and prepared using spade, fork, hoe, rake, mattock and a stone roller. Tools were generally cheap at this time. Specialist tools included forks for harvesting asparagus and carrot, and for moving manure. Watering pots originally consisted of earthenware vessels with a narrow neck and a broad base, punctured with holes. They were replaced from the late 17th century by the watering can. Dung barrows and wheelbarrows were also in use at this time.

Glass, in the form of bell glass and flat glass which was used in cloches and frames, was expensive. The eventual invention of the sheet glass technique (1833) was a boon to the trade but glass remained expensive although the repeal of the glass tax in 1851 did help to make it more affordable.

The most common crops that were cultivated in market gardens included: parsnips, carrots, turnips, cabbage, cauliflower, peas & beans, cucumbers, radish and lettuce, plus some herbs, rhubarb and soft fruit. Some growers started to specialise in more profitable crops by the early 18th century: asparagus, celery, melons and mushrooms being typical examples.

In addition to market gardens there existed a hybrid called a farm-garden, part garden and part field. Farm-gardens varied in their similarity to market gardens. Places that were close to market gardens were likely to copy their techniques quite closely, e.g. Fulham, Putney, Barnes and Richmond. More remote farm-gardens were less likely to crop as intensively, employ the bed system or use large amounts of manure. These places would tend to concentrate on crops that would travel well, such as root vegetables, onions and cabbage.

Walled Kitchen Gardens

They were the preserve of large country houses, the first appearing in the late 16th century, although it was to be the 18th and 19th centuries when they became most popular.

Just as servants in a country house were meant to operate largely unseen, so the general idea of the walled kitchen garden was that it should be close to the house, but it should not spoil the view. High walls obviously helped in this respect. Having said that, they could be sited up to a mile away on larger estates, complete with a concealed service road as gardeners were also ordered to keep out of sight.

In general, this approach differed from in France and Italy where the potager garden was popular. It combined flowers with vegetables, fruit and herbs, all laid out in a pleasing, ornamental manner that was meant to be seen.

A walled kitchen garden was rectangular in shape with an east-west orientation. The wall helped to keep animals and thieves out, as well as providing a beneficial microclimate. Fruit such as peaches and nectarine were grown next to a south-facing wall, often trained in an espalier shape. The arrival of heated greenhouses in the 18th century allowed exotic items such as pineapple to be grown, while hotbeds for bringing on early crops might be sited in a melonry or frame yard, as they were unsightly.

Some rules of thumb that tended to be adopted included:

- one acre would feed 12 people

- Two or three gardeners were required for each acre

- and 1/3rd of the area would be occupied by glasshouses, frames and pits

Queen Victoria’s kitchen garden at Windsor was eventually 31 acres.

Walled kitchen gardens went out of fashion after World War II with the availability of relatively cheap fruit and vegetables which could be imported from all parts of the globe, inevitably leading to their decline with a significant number now in ruins.

Allotments

As mentioned, the Open Field System gradually started to disappear from the 15th century onwards as land was privatised via enclosure acts. 3,500 acts of Parliament went on the statute book between 1700 and 1860. The need for some form of replacement led slowly, very slowly, to the creation of allotments.

While the occasional site can be found from the 14th century, allotments as we know them date from the 1760s. They were mostly to be found in rural areas on plots rented from the landed gentry which could each be up to two acres in size. Growth in the number of plots was extremely slow for the next century, not helped by opposition from many farmers and some members of the aristocracy, which was a factor in delaying the passing of any meaningful legislation that might assist the increase in the number of plots.

A continued diet of bread, cheese and occasional meat among the poor meant that cereals were mainly grown on these allotments. Potatoes were relatively slow to catch on, it being well into the 19th century before they began to be accepted as a staple diet.

The Industrial Revolution led to a change from an agrarian population to a more urban populace as towns rapidly increased in size during the 19th century, which in turn led to a demand for urban allotments.

Various acts of parliament were passed from the 1880s through to 1907 to aid the growth in the number of plots, finally resulting in the Small Holdings & Allotments Act (1908) which was a general tidying up of these acts. It included a statement that councils must recover costs, i.e. they could not run allotments as a loss-making activity; and it required that notice to quit had to be given to plot holders. This act is still on the statute books today, and it tends to be the one that is most frequently referred to.

Urban plots, which were mostly provided by councils, were called allotment gardens and generally had a standard size of 10 poles (250 square metres).

The number of allotments grew from 243,000 in 1873, to 445,000 in 1890, and on up to 600,000 in 1913 just prior to the First World War. They subsequently peaked at 1.5m during the First World War and 1.75m during the Second World War. Reasons for this marked increase included: a higher political profile; changes in local government organisation; a rash of legislation; and most notably, food shortages during the two World Wars when parks, land beside railway lines and even bombed areas were put under the spade.

However, the demand for allotments declined after World War II, leading to a fairly rapid reduction in plot numbers. There are now currently estimated to be around 330,000. The average size of plot has also tended to decrease due to factors such as a lack of land plus an increasing demand for smaller plots as individuals have other calls on their time, be it job, family or other leisure activities

Up as far as the 1960s the typical urban plot holder might major on growing potatoes, brassicas, beans, onions, root crops, rhubarb and some soft fruit.

It was from the 1970s onwards that there was a gradual move to include more adventurous crops such as tomatoes, peppers, squashes, aubergines, et cetera.

Appendix – Origins of Selected Vegetables

| Vegetable | Notes re origins |

| Asparagus | Wild forms in Central & Southern Europe plus N. Africa. Ancient Greeks credited with the introduction of the cultivated form around 500 BCE. Although there are claims that it may be much older |

| Aubergine | Dates back to India in prehistory; first recorded cultivation in China in 6th century CE. |

| Beetroot | Middle East 2500 BCE – first written mention occurs around 8th century BCE. |

| Broad bean | Mediterranean and Middle East 3000 BCE, the common bean goes back earlier, possibly 6500BCE. |

| Brussels Sprouts | The forerunner of today’s sprout may be Roman in origin; the modern day sprout dates from c. 1200 CE in Belgium |

| Cabbage | China and Mediterranean area, known to the Ancient Greeks (500-1000 BCE). |

| Sweet Pepper | Americas – at least 2000 years old, possibly older. Brought to Europe by the Spaniards at the end of the 15th century. |

| Carrot | Afghanistan c. 3000 BCE. It was black and bitter. The modern day “sweet” red carrot was bred by the Dutch in the 16th century. |

| Cauliflower | Dates back to ancient times. Modern day version dates from the Mediterranean area around the 13th century |

| Celeriac | Originated around the Mediterranean area 1500-1000BCE |

| Celery | Asia Minor / Middle East c. 1500 BCE; main written evidence points to the Ancient Greeks introducing the cultivated version |

| Chilli Pepper | Americas 5200-3400 BCE, brought to Europe by the Spanish in the 16th century. |

| Cucumber | Native to India – has been cultivated for at least 3000 years |

| French Bean | Americas – at least 7000 years old – brought to Europe by the Spanish in the 16th century |

| Gherkin | Probably similar history to the cucumber viz. native to India – has been cultivated for at least 3000 years |

| Globe Artichoke | Middle East and North Africa 2000 BCE |

| Jerusalem Artichoke | Grown by native Americans, brought to Europe in the 16th century |

| Kohl Rabi | Known to the Romans; the modern type dates back to the late 18th century |

| Leek | Middle East 2000 BCE |

| Lettuce | Egypt 2000BCE |

| Mangel Wurzel | Developed in the German Rhineland in the early 1700s. Introduced into England in 1786 |

| Onion | Middle East 5000 BCE |

| Parsnip | Cultivated by the Romans, possibly around 500BCE |

| Pea | Middle East / Asia 7500 BCE, possibly earlier |

| Potato | Peru / Columbia 5000 BCE, brought to Europe by the Spanish in the 16th century |

| Radish | China or Asia Minor. Ancient Greeks cultivated them (1000-500 BCE) |

| Runner Bean | Americas – at least 2000 years old, probably older – brought to England in the 17th century |

| Squash | Americas (8000-6000 BCE), brought to Europe by the Spanish in the 16th century |

| Swede | N. Europe in the 17th century |

| Tomato | Peru or Mexico probably around 1000-500 BCE, brought to Europe by the Spanish in the 16th century |

| Turnip | Mediterranean area and Asia Minor; probably predates the Romans although they come to our notice at that time. |

Bibliography & Further Reading

A reasonable amount of the content in this article comes from two of my other more detailed pieces. Each includes its own Bibliography and Further Reading section.

A Brief History of Allotments in England

A Brief History of Cultivation in England prior to the Allotment Movement

In addition ..

Campbell,S., Walled Kitchen Gardens, Shire Library, Oxford, 2006

Kitchen Gardens – A Brief History and Where to Find One | Art Fund

Produce Gardens (Chapter 4) – Gardens of the Roman Empire

Gardens of ancient Egypt – Wikipedia

Gardens in Ancient Egypt | National Museums Liverpool

Farmers, Crops and Farm Work in Ancient Egypt | Middle East And North Africa — Facts and Details

Food in middle ages England | Food Unpacked

Monasteries | Travel Inspiration – Monastic Gardens: Cultivating the Soul Through the Centuries

What the St Gall Plan tells us about Medieval Monasteries – Medievalists.net

Codex_Sangallensis_1092_recto.jpg (2048×1409)

Exton Park’s walled kitchen garden – Glamping Hideaways

Acknowledgements

All images have been found on the Internet. The captions are links to the creators. Please contact me if you consider that I have infringed any copyright.

Version History

Version 0.1 – 16th Oct 2025 – initial draft

Version 1.0 – 17th Oct 2025 – official version

Version 1.1 – 10th Nov 2025 – several minor changes.