I hope that this relatively short potted history is suitable reading for those who want more than just a simple one or two-page overview, but who may be put off by full-blown books, scholarly works that are principally aimed at students and historians rather than general readers. My aim is to provide a modest piece which is both informative and readable.

Fill in and submit the form on the Contact Me page if you have any questions or feedback.

Contents

Asceticism

First Christian Hermit and Cenobites

First Appearances in the Western Roman Empire

Benedict of Nursia

Celtic Monks in Ireland, Iona and Northumbria

Arrival of Roman-led Christianity

Cuthbert

English Benedictine Reform

Arrival of the Normans

New Monastic Orders

English Benedictine Congregation

Mendicant Orders

Hospitals

Literacy and Learning

Manual Labour

The Start of the Decline

The Dissolution of the Monasteries

The Effects of the Dissolution

The Restoration of Religious Houses

The Rule of St. Benedict

Monastic Land

Monks’ Appearance

Brewing

Bibliography and Further Reading

Introduction

Please note that with regard to dates, BCE (Before the Common Era) and CE (the Common Era) are used in this document instead of BC and AD. Dates from 1000 CE onwards dispense with the CE suffix.

Ascetics (or hermits) predated monasteries, starting on the Indian subcontinent around the middle of the first millennium BCE. The first individual Christian hermits appeared in Egypt in the late 3rd century CE, subsequently leading to the establishment of communities. Monasticism then spread throughout the Eastern Roman Empire before emerging in the West, most notably with St. Benedict of Nursia who introduced his Rule for monastic life.

In the British Isles, Celtic monks appeared in Ireland in the early 6th century CE, extending to Iona in the Hebrides before being becoming established in Northumbria. Meanwhile, Augustine introduced Roman-led Christianity in southern England, moving northwards where the Celtic and Roman traditions clashed.

The Roman tradition gradually won out, and monasticism became popular until a mixture of abbey sackings by the Vikings from the late 8th century and a general moral decline took place. The English Benedictine Reform from the middle of the 10th century helped to improve matters, although it was to be the influence of the reforms on the Continent which had a greater impact in England after the Normans arrived. They led to the formation of new monastic orders that observed a strict version of the Rule of Benedict. However, they also suffered something of a decline in due course, leading to further attempts at reform with the introduction of the friars in the 13th century.

Monasticism in England began to decline in the 14th century, the appearance of the Black Death being a major factor. However, it was the Dissolution of the Monasteries during Henry VIII’s reign, after his break with the Catholic Church in Rome, that signalled the end.

It was to be the Victorian era before the movement was resurrected, principally after the passing of the Catholic Emancipation Act (1829). Catholic monasteries and convents were established, soon accompanied by Anglican Religious Communities, albeit the overall movement was on a much smaller scale than had been found in medieval times.

Asceticism

Ascetic – characterized by severe self-discipline and abstention from all forms of indulgence, typically for religious reasons.

Oxford Languages

Dictionary definitions of the word ascetic invariably use the adjective “severe” (or similar). The majority of religions accommodate some form of asceticism although the degree of severity may vary from “lite” to very severe. An ascetic may have a desire to get away from the rest of humanity, although perversely that can attract followers who are keen to understand how he manages to exist.

The first known ascetics are thought to have appeared around the same period (500-600 BCE) in Jainism, Buddhism and Hinduism on the Indian subcontinent. Subsequently, around the third and fourth centuries BCE, the Stoics, Plato and other Greek philosophers discussed and promoted the ideas of self-discipline and abstention.

First Christian Hermits and Cenobites

The first ascetics in the Christian world were known as hermits (or eremites), and they appeared in Egypt. St. Paul of Thebes is traditionally regarded as the first hermit to retreat to the desert. St. Anthony the Great (251?-356 CE) subsequently retreated into the Scetes desert around 270 CE, a fact which brought him renown and attracted disciples. These hermits generally came to be known as the Desert Fathers.

St. Pachomius, a Roman army conscript who had managed to avoid any fighting, was responsible for founding the first cenobitic (or communal) monastery, also in Egypt, around 318 CE, while his sister subsequently became the abbess of a monastery for women. Double monasteries, that is institutions which catered for separate communities of males and females, also date back to this period.

Monasteries then spread throughout the eastern half of the Roman Empire. It was St. Basil the Great, bishop of Caesarea in Asia Minor, who formulated rules for communal living in monasteries in the middle of the 4th century CE, covering topics such as obedience, times for liturgical prayer, along with thoughts on manual and mental labour. Pachomius and Basil are both regarded as the fathers of communal monasticism in Eastern Christianity.

First Appearances in the Western Roman Empire

In the Western Roman Empire, St. Martin of Tours founded a monastery at Ligugé in Gaul in 361 CE where the monks initially followed the ways of the Desert Fathers of Egypt, each living in a separate hut. He subsequently also founded Marmoutier Abbey, outside Tours, in 372 CE.

St. John Cassian who was based in Constantinople left after being involved in a theological dispute, and he moved to Rome to plead his case with pope Innocent I. Around 420 CE he accepted an invitation from the pontiff to found a monastery at Marseille which would cater for both men and women. Cassian is generally renowned for his role in bringing the ideas and practices of monasticism in the eastern empire to the west, and writing a series of rules which laid out recommendations for daily life in a monastery.

Benedict of Nursia

In the following century, St. Benedict of Nursia in Italy was another hermit who attracted disciples. He went on to establish twelve communities for monks at Subiaco, Lazio near Rome, before leaving to found the celebrated monastery at Monte Cassino in 530 CE.

He is most noted for writing his Rule which was based on the work of St. John Cassian. It is composed of 73 short chapters that map out the monastic day which is to include periods of: communal and private prayer, sleep, spiritual reading and manual labour. It also discusses how to run a monastery efficiently. Benedict’s Rule became popular because it was considered to be moderate in tone, not overly zealous.

Celtic Monks in Ireland, Iona and Northumbria

Monasticism appeared in Ireland in the early 6th century CE. Although he was not the first monk, St. Finnian of Clonard is regarded as the father of the monastic movement on that island. He is thought to have studied at Tours, before spending time as a monk in Wales. His monastery at Clonard in County Meath, founded in 520 CE, was based on the principles of the Desert Fathers in Egypt, coupled with his own experiences in Wales. He was an eminent teacher, and a number of his pupils subsequently became the founding fathers of other monasteries across Ireland.

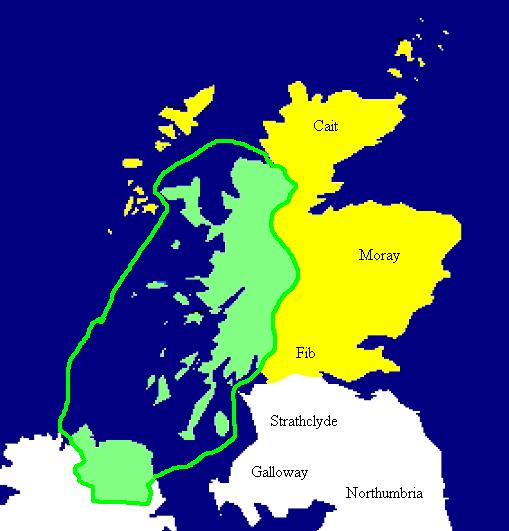

St. Columba, one such pupil at Clonard, is said to have been exiled after a dispute. He went on to found the abbey at Iona in the Hebrides in 563 CE. The Hebrides were part of the Gaelic kingdom of Dál Riata at that time, which encompassed areas of Northern Ireland and Western Scotland.

Æthelfrith, the ruler of Bernicia and Deira (Northumbria) was killed in 616 CE, resulting in his young son Oswald fleeing to Dál Riata where he converted to Christianity. He returned in 633 CE, and after becoming overlord of Northumbria, one of his first tasks was to ask Iona to send someone to establish Christianity in Northumbria. Lindisfarne, on Holy Island not far from Bamburgh Castle, was subsequently founded around 634 CE by St. Aidan.

Other Celtic monasteries followed in the north east of England, including: Whitby Abbey, a double monastery which was founded in 657 CE; and Monkwearmouth-Jarrow Abbey, the former house being established around 674 CE and the latter ten years later.

Arrival of Roman-led Christianity

While there had previously been some embryonic signs of Christianity in Southern England during the early 4th century CE after the Roman Emperor, Constantine the Great, had legitimised the religion, it is considered that it returned to being pagan after the Romans left these shores in 410 CE.

Pope Gregory I sent Augustine to Britain in 597 CE to convert the Anglo Saxons. He landed in Kent where Æthelberht gave him land, which he used to set up a diocesan see at Canterbury. Æthelberht became the first Anglo Saxon ruler to be baptised in 601 CE. However, it was not until the middle of the 7th century that East Anglian, Mercian and Wessex rulers were baptised, followed by Sussex in 681 CE.

This Roman-led conversion gradually spread northwards, reaching Northumbria where it almost inevitably clashed with the incumbent clergy who followed the Celtic traditions that had come from Ireland and Dál Riata. Note that we are talking about relatively minor differences between the two factions, not any fundamental theological issues. King Oswiu of Northumbria summoned representatives of the Celtic and Roman traditions to listen to a debate on their respective differences, known as the Synod of Whitby (664 CE). After listening to the debate, Oswiu decided that his kingdom would adopt the Roman traditions, which included the method of calculating Easter, the specifics of the baptismal ceremony and the style of monastic tonsure.

An equally important event in the history of the English Church around this time was the work of Theodore of Tarsus. He was appointed Archbishop of Canterbury in 668 CE, and quickly instituted a systematic review of the nascent English Church. He eventually summoned the Synod of Hertford in 673 CE when he laid out a whole series of reforms. With respect to monasteries, he said that bishops should not interfere with them, and that monks should not be itinerant.

Cuthbert

Mention should be made of St. Cuthbert, a renowned hermit who had grown up in the Celtic tradition and had subsequently become prior and then bishop at Lindisfarne. He seems to have accepted the result of the Synod of Whitby, although the majority of his monks at Lindisfarne did not. It is said that, feeling the approach of death, he returned to the life of a hermit on the remote island of Inner Farne.

A cult was subsequently established around Cuthbert when various healing miracles were attributed to him after his death. His status was arguably magnified by claims that his body was still showing no signs of decay even as far ahead as the Dissolution of the Monasteries in the 16th century.

English Benedictine Reform

While monasticism, generally adhering to a range of rules, was initially popular, it had gradually began to decline by the beginning of the 9th century. Viking raids were a major contributory factor, wealthy monasteries being seen as easy targets for the Danes. The sacking of Lindisfarne in 793 CE is generally recognised as the official start of these raids. Nearby Whitby and Monkwearmouth-Jarrow were also sacked, the former being subsequently deserted for 200 years, while the latter was briefly revived after the Norman Conquest. Other factors included a general moral decline which saw situations where many monks owned property, were married, and did not actually live in a monastery.

Attempts to arrest this decline of the monasteries were started from the middle of 10th century, led by Dunstan, Archbishop of Canterbury, Æthelwold, Bishop of Winchester and Oswald, Archbishop of York. All three were members of the aristocracy, and both Dunstan and Æthelwold had spells as advisors to the king of England. King Edgar (959 to 975 CE) was particularly supportive of the reforms, which included the promotion of celibacy, life in enclosed monasteries, and a daily routine according to the Rule of Benedict.

Unfortunately, the reform stalled somewhat from the late 10th century, due in parts to: renewed Viking attacks; higher taxation; disputes over land; and the reign of the Danish king Cnut. From a monastic viewpoint, Edward the Confessor’s subsequent support of monasteries might be regarded as mixed. While he tended to appoint secular bishops rather than monastic ones, he did endow the monastery of St. Peter, better known to us as Westminster Abbey.

Arrival of the Normans

At the time of the Norman Conquest, it is estimated that 50% of the clergy were regular, that is they lived in monasteries, while the other 50% were secular, that is they lived among the general populace. Benedictine reforms had also taken place on the Continent, arguably to greater effect than in Britain. By 1135, under the influence of the Normans, there had been a 4-5 fold increase in the numbers of monks and monasteries, while 10 out of 19 cathedrals now had monasteries attached to them.

New Monastic Orders

The monastic reforms that had been in progress on the Continent led to the establishment of new monastic orders which eventually found their way to Britain. They included the Cluniacs, Cistercians, Augustinians and Carthusians.

Cluny Abbey had been founded by William I, the Duke of Aquitaine, in 910 CE. It introduced a stricter observance of Benedict’s Rule, and arguably influenced those reforms which were introduced in England 50 years later by Dunstan and co. Lewes Priory was the first Cluniac house in England in 1081, leading to a total of 35 monasteries by the time of the Dissolution.

The Cistercians were established at Citeaux, near Dijon, in 1098. They also implemented a strict observance of Benedict’s Rule, along with ideas which were formulated by St. Bernard of Clairvaux, a strong intellectual member of the order who sometimes came to be called “the conscience of Christendom”, probably due to his strong advocacy of the crusades.

The Cistercians, also known as the White Monks due to the colour of their cowl, quickly overtook the Cluniacs as the most powerful monastic order. Waverley Abbey in Surrey was their first house in England, founded in 1128. Rievaulx in Yorkshire followed in 1131. Seven further abbeys had been established in that county by 1150, and these eight houses formed the hub of Cistercian life in Britain. Over 100 abbeys were eventually to be founded in this country. Their ideas on self-sufficiency, which we will cover later, tended to attract them to rural settings.

The Augustinian Canons regular, also known as the Black Canons, can be dated back to the 4th century CE, principally in Italy. Although they were influenced by Augustine of Hippo, they were not founded by him. Moral decline eventually led to reform in the 11th century, principally instigated by Hildebrand, later pope Gregory VII. They became known for hospitality, caring for the sick and other charitable works plus active spiritual care of the local population. Their first house in England was at Colchester in 1096, followed by Holy Trinity at Aldgate in London in 1108. By the time of the death of Henry II in 1189, there were 54 houses in this country.

The Carthusians were founded by Bruno of Cologne in 1084. They lived by their own rules, called Statutes, which included a more profound vow of silence and greater amounts of solitude. They had 10 houses in Britain by the time of the Dissolution, the first being Witham Abbey in Somerset which was founded by Henry II in 1181 as penance for the murder of Thomas Becket. The London Charterhouse, built on the site of a Black Death burial ground in 1371, was the largest Carthusian monastery in the world. Charterhouse is the English word for a Carthusian monastery.

English Benedictine Congregation

These new monastic orders all had some form of leadership, be it an abbot general or a motherhouse. This was not so for Benedictine monasteries which were autonomous institutions. This changed in 1216 when the Holy See called for the setting up of an English Benedictine Congregation, effectively a loose-coupling of Benedictine monasteries.

The Congregation remained in existence until the Dissolution of the Monasteries (1535-1540). The idea was resurrected around Europe from the early 17th century. Multiple congregations subsequently appeared which are nowadays affiliated to the international Benedictine Confederation.

Mendicant Orders

Religious orders such as the Cistercians and Cluniacs which were established to reform the monastic movement, eventually fell from grace, much as their predecessors had done. For example, while the individual monks may have taken vows of poverty, the monasteries had become immensely wealthy organisations through the land that they came to own.

This led to the establishment of mendicant orders, evangelists really, but typically known as friars. They had minimal property, preached among the community and relied on charitable donations from the local populace. Pope Innocent III, who had recognised the need for further reform, gave his blessing to the formation of the Franciscan and Dominican orders, although mendicant orders were not to be officially recognised by the Church until the Second Council of Lyon in 1274. The Franciscans, often known as the Greyfriars, had been founded by Francis of Assisi in 1209, while the Dominicans, the Blackfriars, were founded by the Spaniard, Dominic de Guzman, in 1216. Francis of Assisi also went on to found the Poor Clares, a contemplative order of nuns, and the Third Order, a lay fraternity which adhered to the principles of Franciscan life without taking vows or retreating from the world.

Other mendicant orders included the Carmelites, the Whitefriars, who had probably been founded during the 12th century, and the Austin friars or Augustinians in 1244.

The Dominicans and Franciscans both put heavy emphasis on the education of future members of their orders. The Dominicans set up studiums, initially in university towns such as Paris, Bologna, Montpelier and Oxford. The Italian Dominican Thomas Aquinas and the English Franciscan William Ockham were among the foremost philosophers of the 13th and 14th centuries. On the darker side, members of the Dominican order who taught theology in the universities were often appointed to carry out the various Inquisitions which took place across Europe times from the 1250s right through to the 19th century, although never in England.

Hospitals

Moving on to a brief discussion of monastic activities, let us start with hospitals, covering hospitality, as well as various forms of care for the elderly and sick.

The Latin word hospes means visitor or guest and leads to hospitium (hospitality). Many monasteries provided shelter and hospitality for pilgrims and travellers. They would typically be located in or near major towns, London naturally, or along major routes, for example Reading Abbey. The degree of hospitality varied: for example, guests may be fed in their rooms; or they may eat with the monks, especially if they were monks or members of other religious orders.

Some monasteries were responsible for almshouses which provided accommodation for the poor and the elderly. It is thought that the oldest almshouse foundation in England was the Hospital of St Oswald in Worcester which dates back to c. 990 CE. A bede-house was an almshouse where the residents were frequently called to prayer for the souls of the founder or benefactors.

Leper hospitals (leprosaria) were mostly founded in the 12th and 13th centuries, an indication that leprosy was rife at that time. In 1175, the English Church Council ordered that lepers should not live among the healthy. There were in excess of 300 leper hospitals dotted around the country, situated on the outskirts of towns. Early examples included Harbledown outside Canterbury (1084), St. Giles-in-the-Fields in Holborn, London (1108) and Norwich (1119).

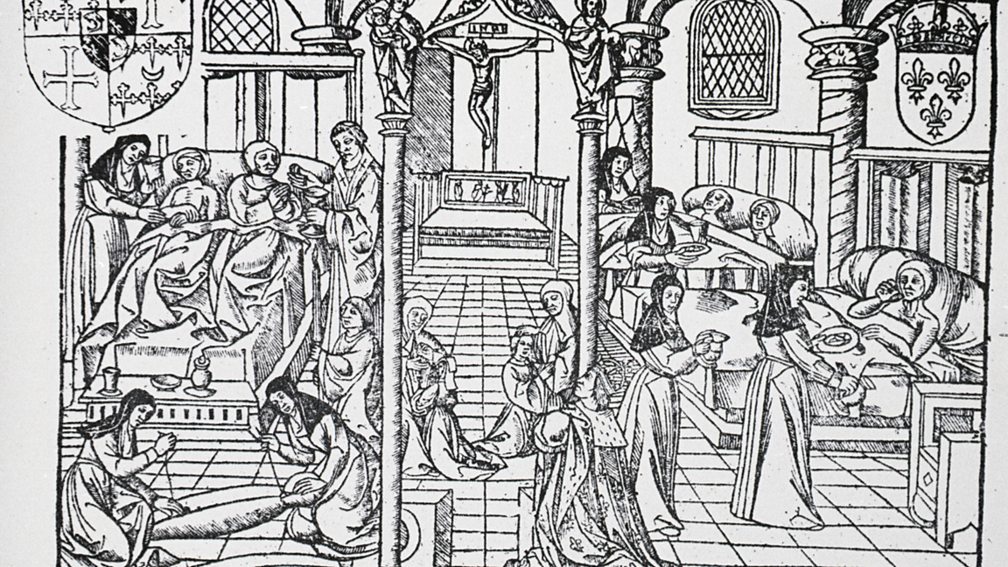

Monasteries would typically have an infirmary to treat the monks when they were sick. It might be a monastery within a monastery, that is it could include its own chapel, dormitory, refectory and toilets. It was also a place where elderly monks could retire to.

Any facilities to treat the local population may have resided within the monastery, or more typically outside it. While these hospitals were run by monks, actual care was more likely to be the job of lay brothers and sisters. St. Leonard’s in York, established in 1137 and run by Augustinian monks / nuns, was the largest hospital in England with over 200 beds. Although there are no figures, St. Bartholomew’s in Smithfield (1123), St. Thomas’s in Southwark (1170s?) and St. John’s Oxford (1231 on the site of the future Magdalen College) are all thought to have been sizeable hospitals which were run by Augustinians. They will have catered for the elderly, as well as the sick. It is unclear to what degree medieval hospitals provided any medical care in the modern sense of that term. They will certainly have ensured that patients were comfortable, warm, clean and fed. These hospitals will also have tended to individuals who arrived on the door-step in need of attention, to clean and dress a wound possibly, outpatients in our terminology.

Literacy and Learning

Monasteries and cathedrals were effectively the sole sources of literacy and learning in England from the late 6th century up to the 12th century. Even afterwards, the so-called secular schools were run by the Church.

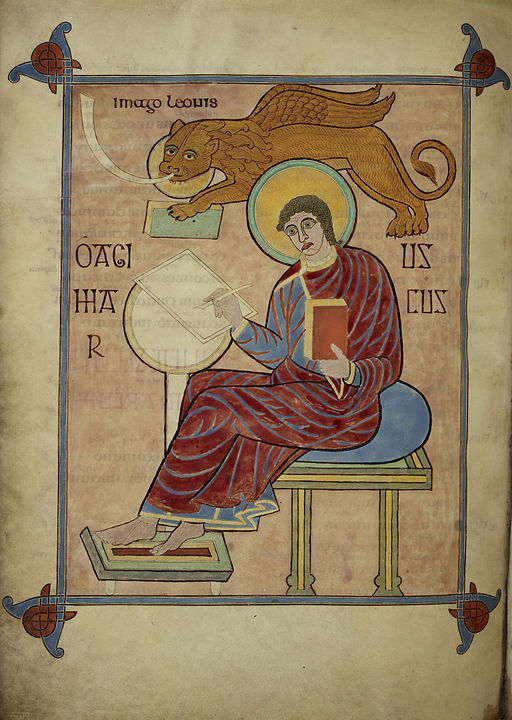

Monasteries were responsible for copying documents and producing illuminated manuscripts, the most notable being the Lindisfarne Gospels which were produced in the early 8th century. The scriptorium was the room where such work was undertaken. It is thought that young monks, possibly even teenagers, made the best scribes, as they were likely to have steadier hands, better eyesight, greater stamina and the ability to withstand extremes of temperature for longer periods.

After Augustine arrived in 597 CE, he quickly needed to train priests, and so he set up two schools in Canterbury, one in the cathedral and one in a monastery, initially known as Saints Peter and Paul. Other schools which were founded in the following century included Winchester (648 CE), Hexham (678 CE) and Malmesbury (709 CE).

Two types of school were developed: grammar schools which provided a general education, naturally slanted towards meeting the needs of the Church; and song schools, more likely to be found in cathedrals, which trained choristers for services.

In the late 8th century, Alcuin’s school at York expanded its curriculum. It taught grammar, rhetoric, law, poetry, astronomy, natural history, arithmetic, geometry, music, and the Scriptures. Alcuin went on to become one of the major intellectual influences on the Carolingian Renaissance, when he was based at Charlemagne’s court in Aachen.

Universities began to appear in the 12th century in places such as Bologna, Paris and Oxford, all under the aegis of the Church, thus providing another source of education.

Few monasteries were founded after 1300, leading to the establishment of secular colleges to fill the gap in the provision of education. They were still Church-based, and their primary aim was typically to train individuals for the priesthood. Over 100 were founded before the Dissolution of the Monasteries, including Arundel (1380), Winchester (1382), Fotheringhay (1430) and Eton (1440).

Outside the Church, a general education was a prerequisite for statesmen and occupations such as lawyers, civil servants and clerks. It is not surprising to find that the vast majority of the Lord Chancellors of England were senior churchmen right through to Cardinal Wolsey in 1529. In addition, clerks in the Royal Chancery were mostly churchmen in minor orders, holding office but not acting as priests, that is they did not administer the sacraments. This continued to be the norm until at least the middle of the 15th century.

Finally, the Church offered a career for those sons who were not likely to inherit the estates of their fathers. This may have been a contributory factor towards the moral decline in monasteries and other religious orders, as some may not have had much of a spiritual calling.

Manual Labour

This section deals principally with agriculture, and in particular the work of the Cistercians.

Many of us probably have a romantic view of monks spending their days alternating between prayer, meditation and working the land. While this modus operandi may have been adopted before the 10th century, it had largely fallen out of favour by the time of the Cistercian and Benedictine orders, except for a small number of monks who may have been responsible for looking after the herb, physic and fruit gardens which were sited within the grounds of an abbey.

The Cistercians and Benedictines allowed illiterate or barely literate individuals to join their orders, not as religious monks but as lay brothers, initially called conversi by the Cistercians. After taking vows of chastity, poverty and obedience, it was these lay brothers who performed manual tasks such as working in the fields, occasionally supplemented by hired labour at peak times such as harvesting.

Although they may have had some land in the immediate vicinity of the abbey the majority of an abbey’s holdings were likely to be disparate farms, called granges, which were meant to be within one day’s journey of the abbey. Granges were typically mixed arable and pasture farms although some were devoted to other purposes such as iron production. A cornerstone of Cistercian economic policy was the exemption, granted by Pope Innocent II in 1132, from the payment of tithes on land which monks cultivated. Other landowners naturally objected to this privilege and it was eventually restricted in 1215 to lands newly brought into cultivation.

Start of the Decline

The height of monastic power in England ran through to the end of the 13th century. Robert Bartlett estimates that by the middle of that century there were 550 religious houses for men and 150 for women.

The decline started in the 14th century which saw the effects of diseases, notably the Black Death which is thought to have killed at least 33% of Europe’s population. This obviously affected monasteries, not least in terms of the ability to recruit monks and good quality lay brothers and sisters.

Other factors included economic depression, political instability and weather problems (a mini-ice age). In the case of the Cistercians, some abbeys may have been forced to lease possessions, even entire granges, to lay tenants. In extreme cases, they had to sell granges.

The Dissolution of the Monasteries

The vast wealth of monastic houses made them an easy target for Henry VIII in his role as head of the English Church after his break with Rome. It is estimated that they owned 25% of the landed wealth in England and Wales. Thomas Cromwell, the king’s chief minister, set about discrediting them and seizing their assets in the period from 1535 up to 1541.

This started with the Suppression of Religious Houses Act (1535) which saw the dissolution of the smaller monasteries. This led to the Pilgrimage of Grace (1536), a popular protest in the north of England against the act, against Henry’s break with Rome, in addition to various economic grievances. It is estimated that 200 individuals were executed after the protest had been put down. The subsequent Suppression of Religious Houses Act (1539) provided for the further dissolution of 552 monasteries and religious houses across the country.

Taking London as an example, twenty-three major religious houses occupying large sites in and around the City were sold off between 1543 and 1547, some falling into the hands of the aristocracy, including the Duke of Norfolk (never mind the historical Catholic credentials of that family!) who inherited the mansion on the site of Holy Trinity Priory and Charterhouse in London. The large London houses (or inns as they were known) of abbots and priors in the Fleet Street, Holborn and Strand areas were also seized, some being turned into large inns for travellers. Somerset House, commissioned by Protector Somerset, replaced the residences of the bishops of Chester, Llandaff and Worcester.

The Effects of the Dissolution

Continuing with London as an example, former monastic areas retained their immunity from City jurisdiction, taxation and trade regulations, which made them appealing to theatres, industry and to criminals. Some were much restricted after James I’s second charter of 1608 but others, such as St. Martin’s Le Grand, lasted in a modified form until 1815, while the Inner and Middle Temple both still claim to be Liberties at the present day.

In general across the country, all abbey treasures were confiscated; libraries were broken up and books destroyed, including illuminated manuscripts. Buildings might be destroyed and the stones used elsewhere, e.g. to build mansion houses in the neighbourhood. Rievaulx and Fountains are classic examples of abbey ruins Alternatively, buildings might be reused for agricultural or industrial purposes.

With regards to individuals, it is claimed that 6,500 out of 8,000 monks and friars managed to find alternative employment, mostly as priests, but it is thought that 2,000 nuns were left destitute.

The education system, such as it was, and hospital care, both of which had largely relied on religious communities, naturally suffered from the Dissolution. In London, this led to the mayor and aldermen appealing to the Crown for assistance, albeit with limited success, certainly not sufficient for London’s needs: Greyfriars, St. Bartholomew’s and Bethlem were granted to the City; St. Thomas’s was eventually reopened; while Christ’s hospital was created in Greyfriars; and St. Katharine’s managed to survive; while Edward VI subsequently relinquished the Bridewell Palace for use as a workhouse / prison.

The Restoration of Religious Houses

There were short-lived signs of a reprieve during the brief reign of the Catholic Mary Tudor (1553-1558), but they just as quickly disappeared with the accession of Elizabeth I.

Catholicism was banned for over 200 years, as were religious communities. There was in fact one small Anglican community at Little Gidding in the 1630s and 1640s which managed to exist on the basis that it was not a formal community, as it had no official Rule, no vows were required and there was no enclosure.

It was to be 1791 when the Catholic Relief Act of that year allowed members of that faith freedom of worship, along with the removal of various other restrictions. Also around this time, in the aftermath of the French Revolution, the British Government allowed some French monks to settle here, leading to the construction of a modest building to house Trappist monks in Dorset. The first monastic building of any size was Downside Abbey, the Benedictine monastery in Somerset, which was erected in the early 1820s.

The Catholic Emancipation Act (1829) effectively withdrew all restrictions which had been placed on Catholics. This led to the significant building of churches, monasteries and convents right through the Victorian era. The architect Augustus Pugin’s gothic revival style was deployed in many of these new monasteries and convents. His convents were designed for a new order, the Sisters of Mercy, which had houses in places such as Bermondsey in London, Handsworth in Birmingham and Mount Vernon in Liverpool.

The surge in religious building was not limited to Catholics, as other faiths, most notably the Church of England, fought to attract worshippers. Anglican Religious Communities began to appear around the middle of the century, kickstarted by the Tractarians, High Anglicans who were part of the Oxford Movement. A community was established in Wantage, Oxfordshire, starting in 1848, followed in the same location by a community for the Sisterhood of St. Mary the Virgin. The Society of Saint Margaret, founded in 1855 with its first convent in East Grinstead, was another early Anglican religious order for women. There are currently over 80 communities across the Anglican Communion.

By the 20th century, there had been reasonable growth in the number of religious communities within both the Anglican and Catholic faiths, although the numbers of monks and nuns were only a fraction of those that were to be found in the High and Later Middle Ages. And even these relatively modest numbers had begun to subside by the beginning of the current century, women arguably being more likely than men to continue to be attracted to a spiritual life.

Odds and Sods

The Rule of Saint Benedict

The Rule of St Benedict consists of a Prologue and seventy-three chapters, ranging from a few lines to several pages. They provide teaching about the basic monastic virtues of humility, silence, and obedience as well as directives for daily living. The Rule prescribes times for common prayer, meditative reading, and manual work; it legislates for the details of common living such as clothing, sleeping arrangements, food and drink, care of the sick, reception of guests, recruitment of new members, journeys away from the monastery, etc. While the Rule does not shun minute instructions, it allows the abbot to determine the particulars of common living according to his wise discretion.

osb.org

A more detailed overview of the Rule can be found in this Wikipedia article.

Monastic Land

Coupar in Perthshire, Scotland provides a good example of the growth of an abbey. It was granted various pieces of land plus the use of forest and stream (for fishing) by the Scottish king, Malcolm IV (1161); later, 60 acres for the abbey plus various lands and wastes from William the Lion (1172-78); subsequently exempted from all tolls, market and ferry charges; additional forest lands from Alexander II (1233); and other bequests from landed families during the 13th century. By 1225 Coupar had 9 granges. It then subsequently rented 400 acres from the Bishop of Moray for sheep farming … and so it went on. By 1304, Coupar had approximately 8 thousand acres.

The Cistercians were particularly strong on self-sufficiency. One of the main ideals of the order was individual poverty and with it the need to be self-sufficient. Of course, they needed land to be self-sufficient and relied on bequests, which became a popular activity among the landed elite as a perceived means of ensuring that they did not go to Hell when they died. Some people suffered as these abbeys acquired land. Peasants were sometimes moved off the land that they had previously cultivated, while others lost the use of what had previously been common land. On the positive side, monks needed labour and would frequently employ these self-same local peasants.

Another example near to where I live was Broomhall Priory for Benedictine nuns which was first mentioned in 1157. It was a wooden construction and nothing remains of the building which is thought to have been close to the Broomhall Farmhouse in present day Sunningdale on the Berkshire / Surrey border. It enjoyed significant royal patronage, particularly during the 13th century, and acquired lands in Egham, Chertsey, Chobham, Winkfield, Sunninghill and Bagshot. However, its fortunes waned and the Priory was closed in 1524. All its possessions were granted to St. John’s College, Cambridge.

Monks’ Appearance

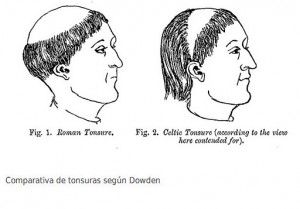

Tonsure involves the cutting or shaving of hair on the scalp as a means of showing religious humility. Many religions have used it. Celtic and Roman tonsures differed although it is not clear what precise form the Celtic version employed. One possibility is shown on the right-hand side of the image below.

The colour of certain items of clothing has been used to differentiate religious orders:

- Benedictine cowl is black (Black Monks)

- Cistercian cowl is white (White Monks)

- Dominican friars wear a black cape over a white habit (Blackfriars)

- Franciscan friars originally wore grey habits (Greyfriars)

- Carmelite friars wear a white cape (Whitefriars)

- Augustinian canons wear black cloaks (Black Canons).

Brewing

Trappist monks, a branch of the Cistercians who were principally situated in the Low Countries, and Benedictine monasteries in Czechoslovakia became the most noted beermakers.

It is claimed that beer was being made in monasteries across Europe from the 5th century. This sounds very credible, especially as people often drank a weak form of beer because the purity of water could not be relied upon. The Cistercians, with their aims of self-sufficiency, are particularly likely to have made beer for passing pilgrims and guests, as well as for their own consumption.

Bibliography and Further Reading

Knowles, D., The Monastic Order in England (940-1216) 2nd ed., Cambridge University Press, 1963

Platt, C., The Monastic Grange in Mediaeval England: A Reassessment, Macmillan, London, 1969

Bartlett, R., England under the Norman and Angevin Kings: 1075-1225 (new Oxford History of England), 2003

Inwood, S., A History of London, 1998, Macmillan

Sargent, A., The Story of the Thames, 2009 and 2013, Amberley Publishing, Stroud

Web Links

The problem with providing links is understanding how long they may be in existence. Apart from simply disappearing, a site may be reorganised, possibly due to the use of different software to create and maintain it, and so the individual URLs may change. It is for this reason that I tend to stick with well-known sites such as Wikipedia where there is a choice on a given topic.

General

History of Monasticism | Monasteries.com

Who’s Who in Monasticism | Monasteries

THE MONKS: Category 5 (The Prayer Foundation)

Early Ascetics, hermits and monasteries

Hindu and Buddhist Asceticism | Encyclopedia.com

Pachomius the Great – Wikipedia

Rule of Saint Benedict – Wikipedia

Irish monasticism (earlychristianireland.net)

Anglo Saxon Period

History of Lindisfarne Priory | English Heritage (english-heritage.org.uk)

Religion in the Anglo-Saxon Kingdoms | The British Library (bl.uk)

Category:Anglo-Saxon monastic houses – Wikipedia

English Benedictine Reform – Wikipedia

11th– 13th Centuries

Monastic Reform under the Normans

United Kingdom – The church and the monastic revival | Britannica

The Cluniac and Cistercian Reforms to Benedictine Monasticism (wondriumdaily.com)

HISTORY OF THE MENDICANT FRIARS (historyworld.net)

Francis of Assisi / The Franciscan Rule – Britannica

The Third Order, Society of St. Francis

Rule of St. Francis – Wikipedia

Hospitals

History of hospitals – Wikipedia

Medieval Hospitals of England | History Today

Monastic Contribution to Medieval Health Care

Medieval England: The Hospital Experience | HistoryExtra

https://blog.nationalarchives.gov.uk/living-with-leprosy-in-late-medieval-england/

Literacy and Learning

The Medieval Scribe and the Art of Writing – The Ultimate History Project

Chancery Clerks – Medieval Londoners (fordham.edu)

The Church in Medieval Europe: Its Role and Importance | TimeMaps

Normans – Monasticism and Education (turton.uk.com)

Education in England: a history – Chapter 1 (educationengland.org.uk)

Dissolution of the Monasteries

Teacher’s Notes – Dissolution of the Monasteries – Historice England

Dissolution of the monasteries – Wikipedia

19th and 20th Centuries

19th and 20th century convents and monasteries – historic England

Odds and Sods

Acknowledgements

Thanks yet again to Janet King and Peter Jackson, regular reviewers of my early drafts, for their feedback. Thanks also to Rona Duncan for her thoughts, notably on the Franciscans. All errors in this document are mine.

All images have been found on the Internet. The captions are links to the creators. Please contact me if you consider that I have infringed any copyright.

Note that this is not a commercial website. All content is freely available and there are no advertisements.

Version History

Version 0.1 January 25th, 2023 – extremely drafty

Version 0.2 January 29th, 2023 – less drafty

Version 0.3 February 1st, 2023 – added material on the Benedictine Congregation, the Rule of Benedict and brewing

Version 1.0 February 7th, 2023 – various minor changes, including information on the Franciscans.