I hope that this potted history is suitable reading for those who want more than just a simple one- or two-page overview, but who may be put off by full blown books, scholarly works that are principally aimed at students and historians rather than general readers. My aim is to provide a modest piece which is both informative and readable.

Fill in and submit the form on the Contact Me page if you have any questions or feedback.

Contents

Britain

Ancient Celtic Culture

Trade with the Continent

British Tribes

Julius Caesar visits Britain

The Roman Invasion of 43 CE

Client Kingdoms

The Roman Army

Early Expansion

Major Roman Positions in Britain

Boudica

After Boudica (60s and 70s CE)

Into Scotland

The Five Good Emperors

Hadrian’s Wall and the Antonine Wall

The Roman Road Network

Towns

Buildings

Local Government

Public Baths

Water Supply

Entertainment and Sporting Venues

Town Walls

London

Mining

Salt

Pottery

Stone

Timber

Bricks and Tiles

Commerce

Merchants

Britain and the Empire from the Third Century

Britannia Superior and Inferior

Military Anarchy and the Tetrarchy

Diocese of Britain

The Great Conspiracy

The Final Years

After 410 CE

Selected Place Names

Legions

Peoples of Scotland

Coinage

Population Size

Slavery

Taxation

Writing Tablets

Sport

Visiting Roman Remains

Bibliography and Further Reading

Introduction

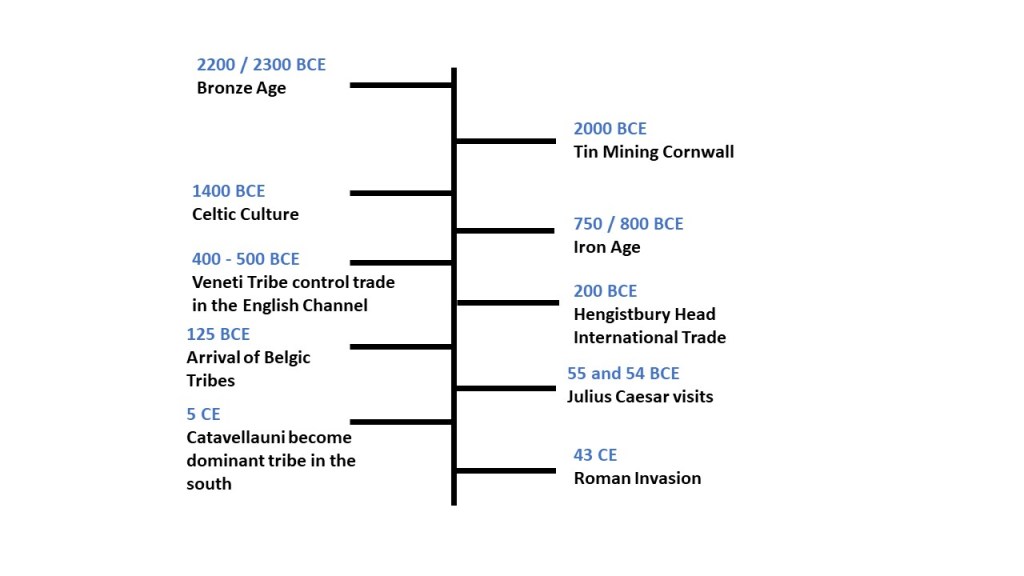

This potted history covers the period from the late Iron Age through to the end of the Roman occupation of Britain at the beginning of the fifth century.

In the south, the late Bronze Age and the Iron Age saw the arrival of various peoples of Belgic origin and the beginnings of significant trade with the Continent. As we rely mainly on the writings of Roman historians for information, not a great deal is known of the north although there is some archaeological evidence of trade with the Continent.

Julius Caesar, in the middle of his conquest of Gaul, flirted briefly with Britain in 55 and 54 BCE, but it was to be the Emperor Claudius who decided on a full-blown invasion in 43 CE.

By 70 CE, after various uprisings, most notably that led by Boudica, the Romans had largely established themselves in the south and had begun to build an urban infrastructure, something which Britain did not have. This consisted of a road network, towns and local government. They also built on the existing industries, bringing their engineering expertise and organisational skills to improve them, as well as introducing many new technologies.

They then moved northwards, to an area that they never managed to fully subdue. It was always regarded as a military zone, the place where the majority of the army tended to be deployed and where frontier walls were eventually built.

Arguably the benefits which accrued from the Roman presence in Britain peaked somewhere between 150 CE and 200 CE. While life and business carried on thereafter, the empire itself began a long and slow decline which culminated in the Romans officially leaving Britain in 410 CE, although the Western Roman Empire staggered on until 476 CE.

Note that modern place names are used throughout the main section of this potted history, although a table showing the modern names alongside their Roman equivalents can be found in the Odds and Sods section.

Finally, you will have seen above that, with respect to dates, I am using BCE (Before the Common Era) and CE (Common Era), rather than BC and AD.

Sources

Modern historians rely on the archaeological record and on the various annals which have been penned by Roman historians, including the following.

Julius Caesar is notable for the commentaries on his Gallic Wars. However, his impartiality is, needless to say, somewhat questionable.

Gaius Cornelius Tacitus (56-122 CE) tends to be the most quoted historian. His Annals and Histories cover the period from the death of the Emperor Augustus in 14 CE to that of Domitian in 96 CE. He also wrote a biography of Agricola, his father-in-law, who served in a military capacity in Britain from 58 CE to 62 CE, returning as governor in 77 CE, a position which he retained until 84 CE.

Strabo (65 BCE–24 CE) was a Greek philosopher and historian who covered the period prior to, and including, Julius Caesar.

Pliny the Elder (23/24 CE-79 CE) principally concentrated on natural history and geography.

Gaius Suetonius Tranquillus, known simply as Suetonius (69–122 CE) wrote biographies of rulers from Julius Caesar through to Domitian.

Lucius Cassius Dio (155–235 CE), originally of Greek origin, wrote The Histories of Rome (80 volumes).

Claudius Ptolemy (c. 100 CE–170 CE), originally of Greco-Egyptian ethnicity, was a polymath, notable in this potted history for his work in the field of cartography.

Up to the Time of the Romans

Britain

Britain was seldom referred to in other parts of the known world before the Bronze Age, and even then it somehow managed to acquire a reputation for being a barbarous place.

From around the 4th century BCE, the Ancient Greeks initially called it Albion, meaning “whiteness”, possibly referring to the white chalk cliffs on the south coast. The reference may be attributable to Pytheas of Massilia (Marseille) who is said to have sailed around these islands at that time. However, the Greeks subsequently began to call it Prettannia or Brettannia.

Ancient Celtic Culture

Diverse tribes across Europe came to share a common culture during the late Bronze Age and the Iron Age. It is thought that the main drivers, or influencers, were three closely related groups, starting with the Urnfield culture in the Upper Danube from around 1300 BCE, although little is known about them.

They were followed by the Hallstatt culture, the name of a site in Southern Austria, which existed from c. 1200 BCE to c. 450 BCE. The area was rich in resources such as salt, iron and copper, and trade along waterways was probably the primary means by which their culture spread. Although it extended to both the east and the west, it was to the west that the ancient Celtic culture would develop.

And finally, the third influencer was the La Tene culture, named after a site on the shores of Lake Neuchâtel, which dates from c. 450 BCE to c. 50 BCE. It also spread across much of Europe, from Ireland in the west to Romania in the east, once again initially via trade. Their culture is arguably best known for its art which included spirals and repeating geometrical patterns.

Language was a key component of the Ancient Celtic culture. It is thought that Proto-Celtic was spoken between 1300 and 800 BCE, after which it split into different groups which are categorised as Insular Celtic and Continental Celtic. Insular Celtic was composed of two groups: Brittonic and Goidelic. Brittonic was spoken across Britain at the time of the Romans before being restricted to the west after the later arrival in the east of Germanic tribes such as the Saxons. This group of languages included Welsh, Breton and Cornish, while the Goidelic branch included Scottish Gaelic, Irish Gaelic and Manx.

Apart from language, other significant identifying aspects of the Ancient Celtic culture include religion and artwork.

Trade with the Continent

Tin was being mined in Cornwall from around 2,000 BCE, and it was subsequently traded with the Phoenicians. There is a debate as to whether the Phoenicians actually sailed to Cornwall, or whether the tin was shipped to the near Continent and transported overland to the Mediterranean where the Phoenicians picked it up.

From around 500 BCE the Veneti tribe, based in Armorica (modern day Brittany), began to establish a reputation as a sea-faring tribe which came to dominate trade in the English Channel.

On the south coast, Hengistbury Head, near Christchurch in Dorset, had become a seaport during the Bronze Age, increasing in significance by the late Iron Age when it was arguably the main port on these islands. Indeed, it had become a trading settlement, complete with service industries such as metalworks. The amounts of Armorican coins which have been found in the area indicate trade with the Veneti, while the sheer volume of amphorae, typically used to hold wine and olive oil, provides evidence for trade with Italy. Amphorae have also been found in north Kent and Essex, indicating maritime trade in these areas.

Archaeological finds indicate that Poole Harbour, 25 miles to the west of Hengistbury Head, was also a port in the late Iron Age.

British Tribes

Increases in the population led to pressure for the available land, leading to friction and violence between groups.

It is a matter of some debate where individual tribes came from and when they formed what might be described as political units. Theories relating to the reasons for the movement of peoples from the Continent which have found favour at different times include invasion, migration and cultural diffusion. Some articles limit themselves to using the word “indigenous” where they have no evidence on the subject.

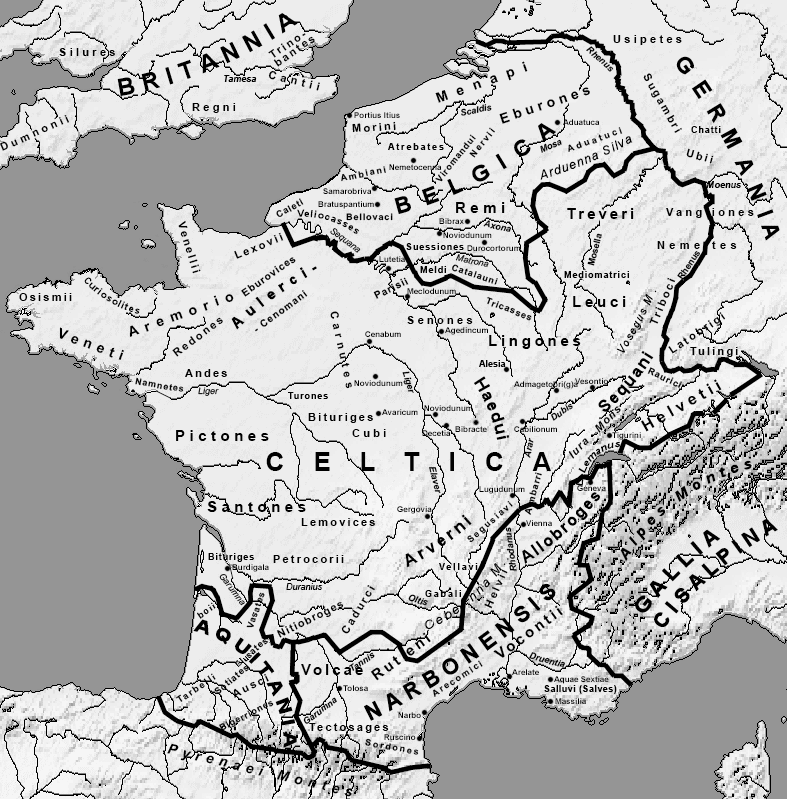

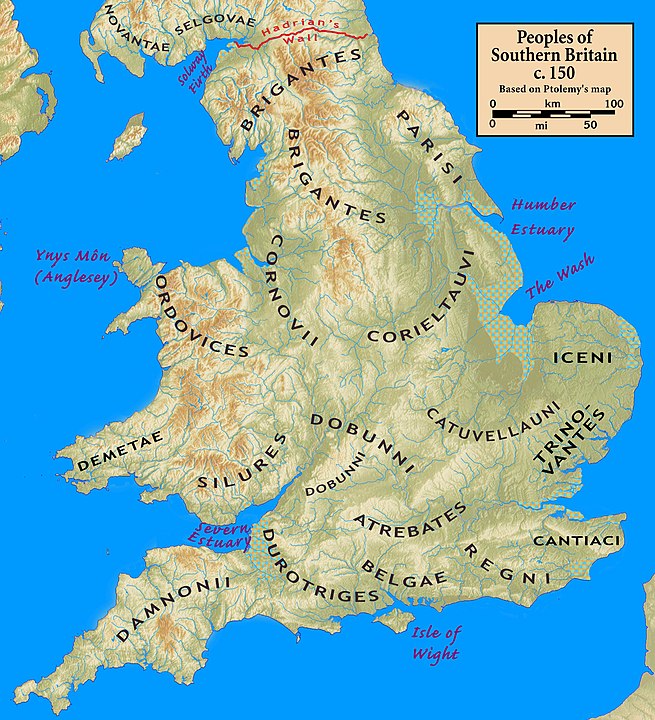

I will limit myself to mentioning a selection of tribes that existed around the time of the Roman invasion. As you will see, people of Belgic origin are frequently mentioned. They were a confederation of tribes which were roughly located in Northern Gaul between the Seine and the Rhine, according to Julius Caesar. However, some had originally migrated from areas to the east of the Rhine, including modern-day Poland.

- The Durotriges were based in modern Dorset and included adjoining parts of Devon, Somerset, Wiltshire and possibly the western side of the Isle of Wight. Hengistbury Head and Poole are to be found in their territory.

- It is claimed that the Belgae invaded from Northern Gaul somewhere around 100 BCE. The tribe was centred on Winchester in Hampshire, becoming the eastern neighbours of the Durotriges. It is suggested that they subsequently became part of the Atrebates domain around 20 BCE.

- The Atrebates could be found to the north and east of the Belgae, occupying parts of Berkshire, Hampshire and Sussex. They were another Belgic tribe that first became notable around the time of Julius Caesar’s visits. They came to be based in Silchester, near Reading.

- The Regninses were a little-known tribe centred on Chichester that may have become vassals of the Atrebates.

- The Cantiaci were another Belgic tribe, possibly hailing originally from the North Sea or Baltic coastline. Their territory was centred on Kent, and Julius Caesar wrote that they had four kings.

- The Catavellauni occupied the territory to the north of the Thames, eventually establishing a settlement at Colchester. They were a Belgic tribe, possibly emanating from Northern Germany, Poland or Bohemia. By the time of Julius Caesar, they were the dominant tribe in southern England

- The Trinovantes, centred on Essex, was a Belgic tribe which may have originally hailed from the same areas as the Cantiaci.

- The Iceni, situated in Norfolk along with parts of Suffolk and Cambridgeshire, were probably yet another Belgic tribe from the North Sea or Baltic coastline.

- The Brigantes occupied the majority of Northern England, an area which was so large that it may well have been a loose confederation of tribes rather than a single political entity. Various sub-tribes have been mentioned, including the Setantii in Lancashire and the Gabrantovices on the North Yorkshire coast.

- The Votadini, little known before the arrival of the Romans, occupied the territory on the east coast from the Firth of Forth down to the River Tyne.

- Finally, Caledonii was the name generally given by the Romans to peoples in Northern Scotland.

Invasion and Conquest

Julius Caesar Visits Britain

The Roman Republic dates from 510 BCE. However, from around 133 BCE it had begun to decay, experiencing periods of political instability, and in 59 BCE three prominent individuals entered into an informal alliance, which is known to us as the First Triumvirate. Julius Caesar was joined by Crassus, primarily known for his great wealth, and Pompey the Great, a military superstar. Arguably the principal reason for the alliance was defence; none wanted one of the others to gain a significant political advantage, and the thought of two of them acting against a single aggressor helped to contain the ambitions of all three.

This pact did help Caesar to be given responsibility for Gaul and Illyria as proconsul (governor) for a period of five years, allowing him to start his conquest of Gaul in 58 BCE, a territory which included modern-day France, Belgium, Luxembourg, parts of Switzerland and Germany, west of the Rhine. The Gallic Wars eventually continued through to 50 BCE. It is generally agreed that there were two principal reasons for his desire to conquer: to further his personal career ambitions; and to relieve his heavy debts of the time.

As mentioned, the Veneti effectively controlled commercial maritime trade in the English Channel. However, as Roman influence grew across Gaul, the Veneti made the mistake of taking on the Roman fleet who they considered to be inferior sailors. They lost the sea battle of Morbihan Gulf in 56 BCE, and the Romans subsequently took control of commercial traffic in the Channel.

Recent archaeological work has confirmed the presence of a Roman fort and neighbouring community in Longy Bay on Alderney in the Channel Islands.

This success over the Veneti may have helped to encourage Caesar to invade Britain. He already had the excuse that some of the Britons had provided military assistance to Gaulish tribes in their battles with the Romans. Other factors probably included: the need to maintain his military momentum; and to further increase his own prestige.

Whatever the reasons, he arrived in 55 BCE on August 26th, somewhat late in the season, for a short and somewhat disastrous visit. He had previously defeated the Gaulish Atrebates and installed Commios as a client king. Caesar sent him ahead to convince the Britons to “seek the protection of Rome”. This ploy failed. The Britons were waiting for Caesar’s forces and prevented the Roman fleet from landing in the Dover area. It is speculated that it was forced to continue on to an area somewhere between Deal and Sandwich.

The Romans were unable to beach their ships, and their relatively small force, consisting of two legions with cavalry, had to wade ashore. The Britons generally harried them, but they were not keen to engage in a pitched battle. Meanwhile, some of the ships were damaged in the high tides. A stalemate ensued, and although Caesar managed victory in one battle, he was forced to accept the fact that he was under-prepared, and so he returned to Gaul after his ships had been repaired.

He returned in the following year, better prepared with five legions and an estimated 2,000 cavalry. It is thought that the fleet landed in Pegwell Bay in Kent, unopposed. Initially, the various tribes in the south-east allied themselves with Cassivellaunus, the probable king of the Catuvellauni. The Roman army, although continually harassed by the Britons, made its way through Kent, crossed the Thames, possibly at Brentford, and reached the headquarters of Cassivellaunus, which it put under siege. Without going into detail, the Romans fought off attempts to relieve their siege, and that, coupled with the fracturing of the precarious alliance among the British tribes, caused Cassivellaunus to surrender. Caesar declared at this point and returned to Gaul, probably having considered that he had saved face after the relative debacle of the previous year.

Although southern Britain gradually came more under the influence of the Roman world, it was to be another 97 years before the Romans returned. Meanwhile, Crassus died in 53 BCE and in 49 BCE Caesar and Pompey fell out, leading to a civil war when Caesar triumphed. He became dictator, a position which he occupied until the Ides of March in 44 BCE when he was assassinated in Rome by Brutus et al.

The Roman Invasion of 43 CE

After Caesar’s “visits”, Britain’s trading and diplomatic relations with the Roman Empire increased, most notably in the south. The volume of artefacts which have been found point to strong trading links, while the Atrebates had definitely established friendly relations with Rome.

After Caligula’s assassination in 41 CE by the Praetorian Guard, Claudius was appointed emperor by the self-same Praetorian Guard during the chaos that ensued. As the Senate should have rubber-stamped the appointment, his position was initially somewhat precarious.

Extending the empire was one way for him to shore up his political position. In the east, Thrace, Lycia and Judaea were annexed, while in the west Claudius set his sights on Britain. Excuses for invasion included: the presence of materials, notably metals; access to more slaves; and the reinstatement of Verica, king of the Atrebates, who had fled to Rome after he had been ousted by Caratacus of the Catavellauni.

It is not clear where the Romans landed, although Richborough and Fishbourne are among the possible candidates. The former is closer to the Thames, while the latter offered a more secure location with the friendly Atrebates close at hand. Of course, other sites may have been involved.

The size of the initial invading force is unknown. It may have been as many as four legions, although it may have been limited to a number of detachments from these, and possibly other, legions.

The Britons were led by Togodumnus, king of the Catavellauni, along with his brother Caratacus. There is some debate on the initial battles. One speculation is that there were two battles, the first being a two-day encounter which was fought near Rochester on the River Medway and the second by the Thames; while the second conjecture is that there was in fact only a single battle.

Further debate surrounds where the Romans crossed the Thames in their pursuit of the Britons, with one possibility being that the river might have been fordable near the Houses of Parliament at the time, but it is of course entirely possible that they crossed the river at several points.

Two things now happened: Togodumnus died suddenly, while Plautius, the general who was leading the Romans, decided to wait for Claudius to arrive, as the emperor wanted to be present for the final victory.

Claudius arrived around late autumn but there was to be no pitched battle. British opposition effectively melted away with eleven kings surrendering in the face of superior forces which now included war elephants that the emperor had brought with him, while Caratacus retreated to the west where he formed an alliance with Welsh tribes. The Romans marched into Colchester which they made their military headquarters and subsequently the administrative capital. After 16 days in Britain, and with the south-east under control, Claudius returned to Rome for his victory parade.

Client Kingdoms

The Romans simply did not have the resources to directly govern conquered kingdoms across the empire and the communities within them. It made sense for them to delegate power to the locals.

At the tribal level, they would ideally appoint one of the warrior elite as king, subsequently to be known as rex sociusque et amicus (king, ally and friend). From the client king’s perspective, he saw it as a means of protecting his position from rivals and from other tribes. From the Roman perspective, they were the senior partner and could always annex a client kingdom if circumstances required it. The Iceni was an example of an early client kingdom after the invasion.

Client kingdoms were also useful in buffer states that adjoined the empire. In Britain, the Atrebates had in fact become a client kingdom from the time of Caesar’s visits, while the Votadini in the north east followed suit in the second century after the Romans had fallen back to Hadrian’s Wall.

At a more local level, there had been no history of urbanisation in Britain, and the Romans created regional administrative units, known as civitates, which were roughly based along the lines of tribal territory. They were governed from a civitas capital. The native aristocracy would come to measure their prestige according to their status within a civitas. We will discuss urbanisation later.

The Roman Army

Before covering their continuing conquest of Britain, let us briefly describe the Romans’ military setup.

The army was composed of legions and auxiliaries. Legions may be thought of as the heavy infantry and auxiliaries as the light infantry. The size of a legion varied, notably over time. For example, in the first century CE a legion might have consisted of between 5,500 and 6,000 men, but by the third century it could have been as little as 1,000 to 1,500 men. The basic unit within a legion was a century, nominally 100 men commanded by a centurion, which were grouped into cohorts, tactical military units which might be described as the equivalent of a modern-day battalion. Legionaries were Roman citizens, originally recruited from areas around Rome. However, as the empire expanded, they were recruited from other parts of Italy and eventually from conquered provinces. By the rule of Trajan in the early second century, it is claimed that between four and five legionaries came from the provinces for every one Italian legionary.

There were typically four legions in Britain during the first century CE, of which II Augusta, IX Hispana and XX Valeria Victrix were constant. By the end of the first century, they were stationed at Caerleon, York and Chester, respectively.

Vexillations were detachments of legionaries that could be dispatched, as the need arose. Apart from war, they may be required for special duties such as building, or they may be sent to the Continent to aid legions there.

Auxiliaries, who had particular skills in regional fighting / techniques, were not Roman citizens. They could be locals or recruited anywhere from across the empire. They were often to be found at the forefront of any fighting, and they typically occupied Roman forts, frequently on the northern frontier.

There is debate over the number of auxiliaries in Britain. One claim states that there were double the number of legionaries, that is some 40,000 in the first century CE. Consisting of infantry, cavalry or a mixture of the two, individual units of auxiliaries were of variable size, although 500 is thought to be a representative number.

Legionary fortresses were necessarily large and required significant building / maintenance effort with large works-depots. Caerleon, a 50-acre site, used massive amounts of timber and manufactured roof and floor tiles on an industrial scale.

Other forts came and went. In the south the only permanent forts were in London and Dover. Elsewhere, major forts may be succeeded by the establishment of towns, such as Cirencester. Alternatively, they could be temporary affairs, notable in the north and in Scotland. They were often timber and turf constructions, for example at Inchtuthil and Strageath. Some might be dismantled and possibly rebuilt at some later period, Birrens in South-West Scotland going through four such iterations.

Finally, marching camps were bivouacs for the army. The Romans used them from around 300 BCE up to 300 CE. A team went ahead and scouted for suitable ground. When one had been identified, each man in the army had a specific task to perform in order to establish a camp, for example digging a ditch, with ramparts being made from the spoil. Camps would provide places where the army could retreat to, if necessary. There is evidence for over 200 such camps in Scotland, some of which have been identified from the air.

Early Expansion

In the year after the invasion, individual Roman legions began the process of conquering other areas.

Vespasian, a future emperor, headed in the direction of the south-west with II Augusta, fighting many battles, capturing twenty settlements, and establishing a fortress at Exeter c. 50 CE. Meanwhile, IX Hispana went northwards, reaching Lincoln, which was closer to the sea than it is today. Ermine Street was built to connect London with Lincoln, while the Fosse Way was developed to link Exeter and Lincoln.

London quickly became the centre of the growing Roman road network. A bridge was built across the Thames, circa. thirty metres downstream from today’s London Bridge, to connect the Kent and Sussex coast with the rest of its territory. Initially, it may have just been a pontoon bridge. Whatever, London’s position as a transport hub for both road and sea traffic, allowed it to quickly develop into the main trading centre in the province.

By 47 CE, the area to the south of the Fosse Way was theoretically under Roman control. However, it was not all plain sailing. Roman plans periodically had to be delayed while they dealt with sporadic uprisings, such as one by the Iceni in East Anglia in that same year. A common reason for unrest was the insistence of the Romans on disarming the tribes.

XIV Gemina headed for the Welsh Marches, basing itself in Wroxeter (Shrewsbury). Caratacus and the Silures tribe successfully used guerrilla tactics to harry the Romans in mid-Wales until he made the mistake of engaging them in a pitched battle in 50 CE, one that he lost. Once again, he managed to escape, fleeing to the north where the Romans were in the process of negotiating with the Brigantes tribe to get them to peacefully accept their patronage and become a client kingdom. Caratacus asked Cartimandua, queen of the Brigantes, to shelter him, but she promptly handed him over to the Romans. He was dispatched to Rome where he lived out the rest of his life after Claudius had spared it.

Although Caratacus was out of the way, Wales continued to be a problem with the Silures tribe successfully continuing to carry out guerrilla raids. Meanwhile in the north, Cartimandua and Venutius, her husband, divorced, leading to a civil war among the Brigantes. She was, as we have seen, pro-Roman, whereas Venutius was definitely not.

The Druids in Britain and Gaul were a concern to the Romans, principally because they operated outside and above the tribal system. Given the propensity for perpetual squabbling between tribes, they were responsible for law and order, in addition to their roles as religious leaders and political advisors. Suetonius Paulinus, governor of Britain at the time, ordered the destruction of their stronghold in Anglesey in 60 or 61 CE.

Major Roman Positions in Britain

Britain was regarded as a military province which meant that the governor (legatus Augusti) normally came from the senatorial rank and had previously served as a consul in Rome. He usually had property worth over 1m sestertii.

The procurator (procurator Augusti) was responsible for finance. He typically came from the equestrian rank, had property worth over 400k sestertii, and had previously filled various imperial administrative positions. It appears that on occasions there may have been more than one Procurator. It should also be noted that the term procurator was used in other contexts, possibly to describe a person who was responsible for an imperial estate.

Occasionally, a Judicial Legate (legatus Augusti iuridicus) was appointed to relieve the load on the governor, and he may also have stood in for him, when required. This position could be regarded as a stepping-stone towards a future appointment as a governor.

Finally, legatus legionis was the commander of a legion.

Boudica

The various problems in Wales and in the north meant that the Roman forces were stretched, and the Iceni took the opportunity to revolt in the south-east in 60/61 CE.

Prasutagus, king of the Iceni, a client kingdom, had died, leaving half of his territory to his daughters and half to the emperor in his will. This upset the Romans, as it should legally have been left solely to Nero, the current emperor. However, the Roman response was totally over the top. The local Romans ransacked the kingdom, flogged Boudica, the widow, and raped her daughters. In addition, they demanded the return of cash donations which the Iceni had previously received from the emperor Claudius and the repayment of loans which had come from Seneca.

This was all too much for the Iceni, who came out of East Anglia, led it is said by Boudica, and destroyed Colchester, London, including the bridge across the Thames, and St. Albans, latterly aided by some of the Trinovantes.

Eventually, Paulinus, the governor, with a full army, tracked them down and defeated them in a set-piece battle which may have taken place somewhere in the Midlands. Although the Romans were heavily outnumbered, the rebels were ill-prepared and the victory was decisive. Tacitus, the historian, claimed that 80,000 Britons were killed, but only 400 Romans. He and Dio, another historian, both stated that Boudica was the principal leader of the revolt, although it is unclear precisely what her role was. They may simply have been wanting to stress how inept Nero et al had been to have allowed a major revolt which had been led by a woman.

After Boudica (60s and 70s)

Until the late 60s Britain was relatively peaceful, there being no attempt by the Romans to conquer other areas. However, the peace in the territory of the Brigantes was disturbed when Cartimandua, the queen, divorced her husband and took his aide as a lover, leading to civil war in the territory. The Romans managed to evacuate her, but they were then faced with the rebellious ex-husband, Venutius.

During the 70s they moved into the territory of the Brigantes, experiencing a number of battles. They eventually managed to establish a framework which allowed them to take overall control of the area, while the Brigantes’ forces hid in the remoter hills and were limited to using guerrilla tactics. Forts were built at Castleford and York to supplement those at Rossington Bridge and Templeborough which both dated back to the 60s. In addition, military installations began to appear further north at Carlisle.

Meanwhile in Wales, Sextus Julius Frontinus, governor of Britain from 73/74 to 77/78 CE, started a successful campaign to defeat the Silures. It was around this time that legionary fortresses were built at Caerleon in South Wales and at Chester.

Into Scotland

During the governorship of Agricola (77/78-84 CE), Tacitus’s father-in-law, the Romans pushed further north into present day Scotland, reaching the Clyde / Forth around 80 / 81 CE, and establishing various forts on the way, including Newstead near Melrose in the Borders.

After continual guerrilla activities, the Caledonii were forced into a pitched battle at Mons Graupius after the Romans had threatened their granaries. The location of this battle is unknown, but according to Tacitus, 10,000 Caledonii were slain, as opposed to only 360 Romans.

A legionary fortress was established at Inchtituthil (Perthshire) around the same time as the victory at Mons Graupius. It was to be the centre of a network of forts which were intended to contain the tribes of the Scottish Highlands. However, it was short-lived, being demolished in 87 / 88 CE.

After the mid-80s, the network of roads and forts in southern Scotland suggests fairly comprehensive control of that area, whereas the Roman hold was much more tenuous further north.

The Five Good Emperors

A brief summary at this point of events across the empire may help to put the building of Hadrian’s Wall and the Antonine Wall into some context.

After Claudius, Nero’s somewhat erratic reign as emperor, which included the Great Fire of Rome, came to a not unexpected end in 68 CE when he committed suicide before the sentence of death by beating, which the Roman Senate had passed, could be carried out. A struggle for the vacant imperial throne ensued, which was eventually won by Vespasian in 69 CE. A period of relative calm followed through to the end of the reign of Domitian in 96 CE, which is not to say that it was trouble-free.

Various modern historians, including Edward Gibbon, the author of The Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire, have called the next five emperors “the good emperors”, considering that they reflect the height of the empire. They were: Nerva (96-98 CE), Trajan (98-117 CE), Hadrian (117-138 CE), Antoninus Pius (138-161 CE) and Marcus Aurelius (161-180 CE). The empire reached its greatest extent during Trajan’s reign. However, his wars in the east (Parthia and Dacia) had stretched the empire too far, and Hadrian subsequently decided to consolidate frontiers and bring an end to expansion.

Pressure on the German frontier began around 150 CE, due principally to population growth, and some towns began to build fortifications. Because Britain was an island, it was of less concern / interest to the Romans than the Rhine / Danube frontiers, because if the latter were breached then Rome would be vulnerable.

Hadrian’s Wall and the Antonine Wall

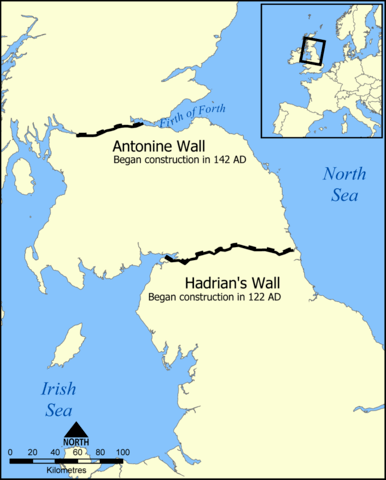

As part of his plan to consolidate frontiers, Hadrian arrived in Britain in 122 CE and ordered the construction of a frontier wall in the north. The Stanegate, or stone road, had been built several decades earlier to link various forts, including Corbridge on the River Tyne and Carlisle on the River Eden. Hadrian’s Wall, 74 miles long, was sited just to the north of this road. It allowed supervised movement between north and south, although the locals considered that it got in the way of doing normal business.

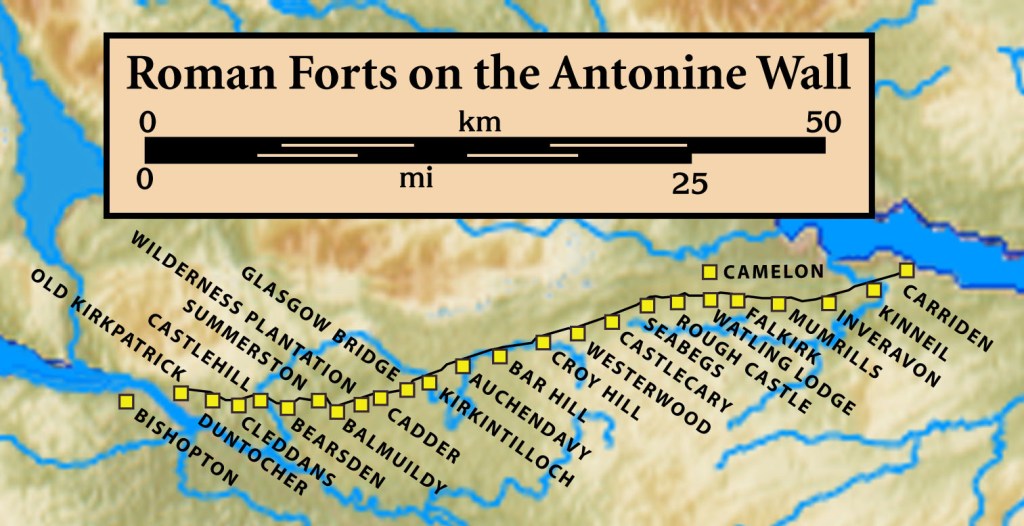

It was probably subsequent pressure from the Caledonii which persuaded the Romans to move their frontier wall further north, resulting in the Antonine Wall that linked the Clyde and the Forth. Started in 142 CE, it was made of wood and turf, built on stone foundations, and was only 39 miles long. It is thought that the wall was protected by 19 forts. However, by the 160s it was given up and the frontier reverted to Hadrian’s Wall.

The Romans experienced significant trouble from the Caledonii in the 170s and early 180s, with the wall being crossed around 180 CE and considerable military casualties being sustained. Ulpius Marcellus, a newly appointed general, managed to bring the situation under control in 184 CE.

Urban Infrastructure

Roman Road Network

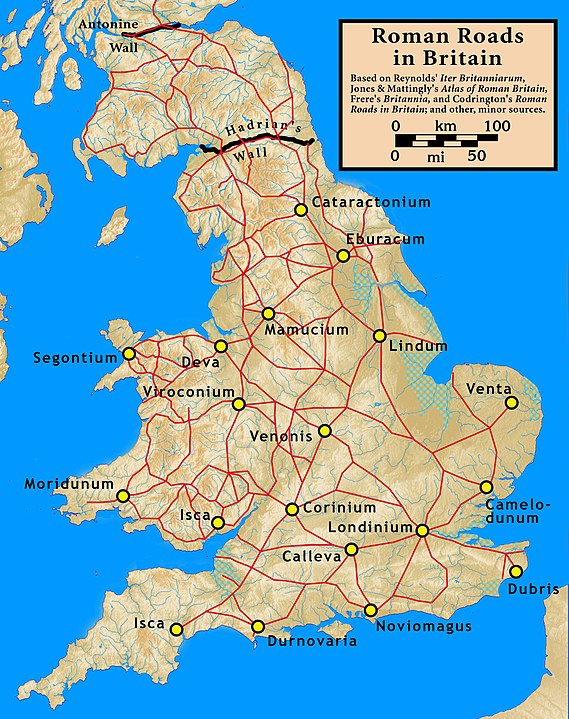

Built from 300 BCE onwards, Roman roads were critical to the success of the empire. Their scope is in part known to us through the following map and register.

The Peutinger Table is an illustrated map of the empire, showing the main routes. Covering twelve sheets of parchment, it was actually produced by a 13th century monk, although it is assumed to be a copy of a Roman original. Eleven of the sheets are to be found in the Nationalbibliothek in Vienna.

The Antonine Itinerary is a register of roads across the empire. The section called Iter Britanniarum contains 15 itineraries which show the settlements along the roads in Britain and the distances between them.

Estimates on the distance covered by Roman-built roads in Britain vary. In the region of 2,000 miles appears to be a common figure for main roads that connected towns. However, other minor roads may account for up to a further 8,000 miles. Most of the major routes must be pre-Roman, even if their alignments were adjusted to make them straighter and wider. The Roman roads had milestones that gave the distance to a destination.

While the Roman names of roads in Italy and Western Europe are known to us, those in Britain are not. The names that we know them by are typically Anglo Saxon: Watling Street (Dover to Wroxeter) may have had multiple names as it was built in discrete sections over a significant period of time; the Fosse Way (Exeter to Lincoln); Ermine Street (London to York via Lincoln); and Dere Street (York to at least as far north as the Antonine Wall).

Roads consisted of a sequence of layers that produced a solid, durable, cambered surface. Widths varied, witness the range of figures that are given by different publications: English Heritage says 20 feet (pedes); Wikipedia mentions 16-26 feet with 23 feet being common. Other figures include: Watling Street at 33 feet; Silchester to Chichester 37 feet; but the Fosse Way was only just over half as wide as Watling Street.

Towns

Before the Romans, there were no towns in Britain, a town arguably being signified by the presence of some public buildings and a form of local government. One possible exception is Silchester, the centre of the Atrebates tribe. They had been on friendly terms with Rome since the time of Julius Caesar, and had been open to Roman influences. The beginnings of a Roman-style town, notably in terms of street planning, possibly date back to 25 BCE, that is prior to the invasion.

Otherwise, the nearest to a town was a large, fortified settlement, called an oppidum by the Romans They were to be found across Britain and the rest of Europe in the Late Iron Age, Colchester being an obvious example.

The Romans had a hierarchy of towns in the provinces, starting with the provincial capital. It was followed by coloniae, colonies of Roman citizens who were often military veterans that had been pensioned off with grants of land. Colchester was initially the site of a legionary fortress which was subsequently converted into the first colonia in Britain. By 60 CE it had a senate house, theatre and temple. Others followed at Lincoln (71 CE), Gloucester (97 CE) and York (sometime in the third century), all places where legions had been based.

Roman Britain was split into civitates, administrative areas which were roughly based on the tribal territories, and which were controlled from the civitas capital. For example, Cirencester became the capital of the Dobunni and Silchester of the Atrebates. The local aristocracy were invited to administer a civitas under the general supervision of the Romans in the provincial capital.

A municipium stood below a colonia but above a civitas in the hierarchy. Whereas a colonia was populated by Roman citizens, a municipium contained “Latin citizens”, a sort of halfway-house which held out the promise of future Roman citizenship after a lifetime of good service. It is thought that St. Albans was the only municipium in Britain.

London’s legal status is unknown, although it became the de facto provincial capital of Britain after Boudica’s revolt.

Civitates were slow to get fully up and running. Even in the south, where Romanisation was more likely to have been accepted, it was well into the second century before they began to mature.

The far South West of England, Central and North Wales plus much of the north remained remote and undeveloped. In the north, the only civitas capital was at Aldborough in North Yorkshire, although military establishments at Carlisle and Corbridge probably helped to fill the administration gap.

In addition, small towns, which had no legal status, would tend to appear in places such as river crossings, road junctions and in close proximity to forts, their presence being naturally dictated by economic and societal needs. They had become particularly noticeable by the fourth century. Most did not have a street grid, strip development along the main road being more usual, or fortifications. There were exceptions. For example, Alchester (Oxfordshire) had a street grid and Water Newton (Cambridgeshire) had a walled section.

Buildings

The forum / basilica complex formed the centre of a town. The forum was a piazza with a covered portico on three sides, behind which might be commercial properties, while the basilica was a multi-purpose public building on the fourth side. London’s complex, the largest in Britain, took 25 years to build. It was 27,772 square metres in area and the basilica was 28 metres high.

The piazza in the forum acted as an open-air market and a general meeting place. It could be supplemented by an indoor market (macellum), examples of which have been found at Leicester, Wroxeter and St. Albans.

Mansiones, large buildings with accommodation for horses, functioned as inns / staging posts, catering mainly for those who were travelling on government business.

Warehouses were to be found. In London for example, they have been located at Regis House near London Bridge and in Southwark on the other side of the Thames.

Streets were laid out on a grid system, and townhouses could have narrow frontages onto a street where various sorts of commercial businesses might be found. Such houses were often made of timber initially, but fire was an obvious danger, and by the second century stone constructions that were not as tightly packed together had begun to replace them. Mosaic floors began to appear in some of these stone buildings, notable examples having been found at Cirencester and St. Albans.

Local Government

The town senate or council (ordo) had 100 representatives who each had to satisfy property qualifications to serve as a councillor (decurion), which meant that we are essentially talking about the wealthy or well-to-do, middle-class individuals. The council met in the curia, a room within the basilica.

Magistrates were elected officials who were appointed in pairs (duoviri iuridicundo) to avoid corruption. They were responsible for the operation of the council, dispensing local justice and organising religious festivals. Other positions included: the aediles who maintained public services and buildings and were responsible for entertainment; and the quaestores who looked after local taxation and expenditure.

To qualify for election to these various positions, a candidate had to be at least 25 years old, and in the case of the duoviri, had not held that position for at least five years.

The wealthy were encouraged, in line with the ideas of Roman civic patronage which had originally been promoted by the emperor Augustus, to endow their communities with facilities such as theatres, temples and entertainments. This would allow them to curry favour and enhance their status. However, there seems to have been fewer examples of philanthropy in Britain than in other parts of Europe.

By the fourth century, public building had largely ceased, apart from defensive works, with the well-to-do now spending their surplus wealth on extravagant extensions to their rural villas.

Public Baths

Public bathing was an important custom in Roman culture, although it was a bit of a novelty in Britain where it was seen as less of a priority. However, Silchester, St. Albans and Bath had installed them by the late first century. They were expensive to operate, needing a continuous supply of clean water and lots of fuel to maintain the necessary temperatures in the different rooms (hot, warm and cold).

The settlement at Bath, which had no official status, was developed in the first century as a very popular religious, healing and leisure complex. It was known to the Romans as Aquae Sulis (the Waters of Sulis) or Aquae Calidae (Hot Springs). The Roman goddess Minerva came to be associated with the Celtic goddess Sulis, and the term Sulis-Minerva was often used. A considerable temple and baths complex surrounded the hot springs.

Water Supply

The typical Roman approach was to locate a water source at a higher level than the town and bring water in via architected aqueducts or by digging conduits into the ground. Magnificent examples of surviving aqueduct bridges can be found at the Pont du Gard in southern France and at Segovia in Spain.

Limited examples of conduits have been found in Britain, including a section on Poundbury Hill which supplied water to Dorchester.

Large wooden water mains have been found at Vindolanda, with other plumbing remains at Carlisle and Cirencester. Waste water was dealt with in a variety of ways, from masonry sewers at York to open channels in the streets at Silchester.

Water supplies to rural villas varied. Siting properties near a river was naturally popular, while wells were another possibility. Wells have also been found in towns, for example chain-driven buckets have been located in Gresham Street, London.

Entertainment and Sporting Venues

Ampitheatres were used for gladiatorial contests and public games. They were oval-shaped auditoria, surrounding a sunken arena, the Colosseum in Rome being the most famous example. In Britain, they were usually built with raised earth banks contained within timber or stone revetments. Canterbury and Colchester had fairly superior examples in Britain.

Theatres with a stage were much less common than amphitheatres. St. Albans is thought to have had the only one in Britain.

Stadia were typically used for chariot racing, an extremely popular sport across the empire. They were typically 250-500 metres in length with a dividing barrier (spina) separating the two sides of the track. The most famous example was the Circus Maximus in Rome which is said to have had room for 250,000 spectators during Trajan’s rule. Given the evidence of chariot warfare in Britain before the Romans, it seems reasonable to suppose that it would also have been popular here. However, the only direct evidence of them in Britain, has been found at Colchester, where remains were recently identified in 2004.

Town Walls

Historians seem unclear as to why the Romans started to build town walls in Britain from around the start of the third century. While a case may possibly be made for towns on coasts or rivers if there was a general fear of invasion by pirates or barbarian tribes, it seems unlikely for inland towns such as Cirencester. Notable walled towns were London, York and Chester.

London

This content has been taken from my potted history of London – part 1.

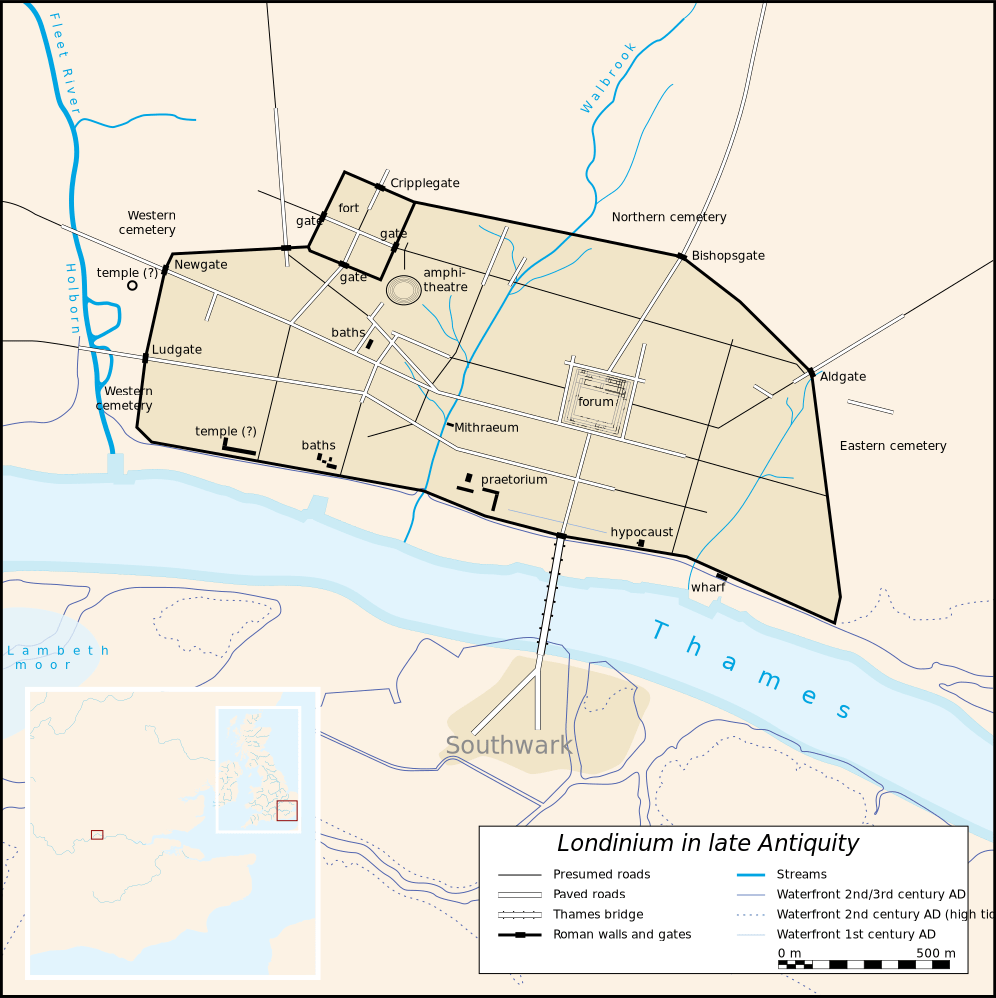

Around 50 CE the Romans constructed a bridge across the Thames where Londinium, as they called it, would come to be situated. It may have been a military pontoon bridge initially, being replaced by a timber bridge around 55 CE.

Situated around 30 metres downstream from the present-day London Bridge, it was a simple crossing point, but it soon attracted private traders who saw the business opportunities that would be presented by the military and other travellers. The tidal range at this period was a modest 1.5 metres, presenting a relatively benign environment for the vessels and port facilities of the age. Within a couple of years, the foreshore near the bridge had been protected by wooden revetments (retaining walls).

The area by the river was generally marshy and hence unsuitable for a settlement. However, two flat-topped gravel hills, now Ludgate Hill and Cornhill, rose 15 metres above the marshes and provided a site for Londinium, which became the central hub of the Roman transport network in southern England.

Progress was halted when London, and its bridge, was razed to the ground by Boudica in 60 or 61 CE. After the uprising had been quelled, London and its bridge was rebuilt. It superseded Colchester as the administrative capital around this time. While the original site has been described as being akin to a frontier town, the new town had the appearance of being planned, with a forum and basilica, remains of which have been located in the area of Leadenhall Market. In addition, a stone amphitheatre, the remains of which have been found in the Guildhall Yard, replaced a timber version early in the second century.

Other buildings in the late first and early second century included: government offices on a 5-acre site in what is now Cannon Street station; a large 12-acre fort in the northwest corner of the town which possibly housed up to 1,500 soldiers, as well as the governor; and a large public bathhouse at the corner of Upper Thames Street and Huggin Hill. There were no deep-water facilities, and it is thought that vessels which used the port were therefore probably on the small side. Evidence of quays and warehouses has been found in Billingsgate.

It is considered that London’s fortunes peaked in the second century when the population may possibly have grown to fifty thousand, but it then went into a decline with a loss of population and a general downturn in the condition of the buildings according to archaeological evidence. It could be that the end of the Roman empire’s expansion resulted in general stagnation and an eventual reduction in trade. A defensive wall was built around 200 CE, an indication of the perceived dangers which might be posed by pirates and barbarian tribes. The wall survived, largely intact, until the 18th century.

Subsequently, internal squabbles among Roman dynastic families led to the empire’s inexorable decline and the inevitable dangers that the raids of various barbarian tribes brought to its stability. A defensive riverside wall which stretched from Blackfriars to the Tower of London was added in the late fourth century.

Industry and Trade

While some of the basic industries were already in place, the Romans brought their organisational and engineering skills, along with the ability to produce on a large scale. Importantly, they also introduced many new technologies, glassmaking and brickmaking being examples.

Mining

It is claimed that Britain’s metal reserves were one reason behind the Roman invasion. This is unlikely to be true, as modern-day Spain and Portugal were the richest places for mineral ore. However, more was obviously useful, particularly for local use.

Lead was mined in the Mendips, Derbyshire, Flintshire, Durham and Northumberland. It was used for plumbing, waterproofing material on roofs and tanks, in the making of pewter (with tin) and bronze (with copper). Silver, often found with lead in an ore called galena, was in part used to mint coins. The Romans also managed to locate gold soon after the invasion at the Dolaucothi mine in Carmarthen.

Iron was much in demand for weaponry, armour, vehicle fittings et cetera. The ore was found in many places, but most notably in the Weald and the Forest of Dean.

Salt

The salt industry had been in existence long before the Romans arrived. Sea water, especially along the Lincolnshire and East Anglian coasts, and brine from inland springs in places such as Middlewich and Nantwich, were evaporated in vessels to produce lumps of salt.

The Romans introduced lead salt pans that were roughly one metre square and 15cm deep. Salt was very important, particularly as a food preservative. Roman soldiers were partly paid in salt, and it is sometimes claimed, though much disputed, that the word salary stems from the Latin word sal (meaning salt).

Pottery

Basic kitchenware items, known as mortaria, were produced locally while finer wares were initially imported, notably Samian from Gaul. However, by the third century pottery industries in Oxfordshire and the Nene Valley were making the majority of finer wares. Amphorae were imported; they arrived filled with wine, olive oil and garum (the fermented fish sauce which was very popular with the Romans).

Stone

Stone resources varied around Britain. Flint, found in the South East, had to be compacted with lime mortar to make it useful for building. Limestone, which was easily worked, was available in the Central Zone (Somerset to Lincolnshire), while sandstone, good for building forts and the like, was plentiful in the north. However, more exotic stone, such as marble, was likely to be imported from elsewhere across the empire.

Timber

Timber was required in large quantities, particularly for the early constructions of forts, townhouses and even public buildings, for example the first forum / basilica complex in Silchester was wooden. It is claimed that the legion which was based at Caerleon would have needed timber from 150 hectares of forest (371 acres) to build their fortress in 75-85 CE.

Joints were crude for heavy duty work such as wharfside timbers, while dowelled joints have been found elsewhere, e.g. in the remains of the Blackfriars ship (first century) and the County Hall ship (fourth century).

Bricks and Tiles

The Romans introduced clay-based bricks and tiles to Britain. The standard size of a brick was 1.5 Roman feet by one foot, although the thickness was less than the modern-day equivalent. They were often stamped with distinctive markings, most notably on flue-tiles. Alternate layers of brick and flint can be found in walls, particularly in the south.

Legions, who made roof and floor tiles for their own buildings on an industrial scale, operated mobile kilns. Commercial tilemakers subsequently appeared, Ashtead in Surrey being a notable example.

Commerce

Strabo said that Britain exported basic agricultural goods such as grain and cattle, plus metals such as gold, silver, iron and tin; and principally imported manufactured goods such as necklaces, amber and glassware, along with foodstuffs such as wine, olives, olive oil and fish sauce.

Merchants

Evidence of merchants has been found in a small number of places: Tiberianus Celerianus (Southwark); Lucius Viducius Placidus a negotiator or merchant from Rouen (York); and Gavo (Vindolanda).

Rural Britain

Villas

The word villa originally meant farm. Pliny the Elder described villa urbana as a place within relatively easy reach of a town where you might retreat to for a couple of days; and villa rusticana as a farmhouse estate further away from town which was run on a day-to-day basis by your servants.

In Britain, by far the greatest concentration of estates was to be found beneath the line of the Fosse Way, notably in the Mendips and Cotswolds in the west and in Kent and Sussex in the east. They were usually found on good agricultural land with ready access to water from springs or rivers. These rural villas typically consisted of the main residential dwelling for the owners, along with necessary farm outbuildings and possibly additional properties sited further away to house the workers on larger estates.

To generalise, the majority of the main houses may have been relatively modest affairs in the first and second centuries. However, whereas the wealthy may have invested in public buildings during that period, the lack of development in urban infrastructure from the third century saw them spending surplus wealth on their own properties, leading to more grand, ostentatious houses, some with beautiful mosaic floors. The fourth century saw the peak of this activity, although it began to tail off significantly from 380 CE, as the end of the Roman occupation approached.

Agriculture

This content has been taken from my Brief History of Cultivation prior to the Allotment Movement.

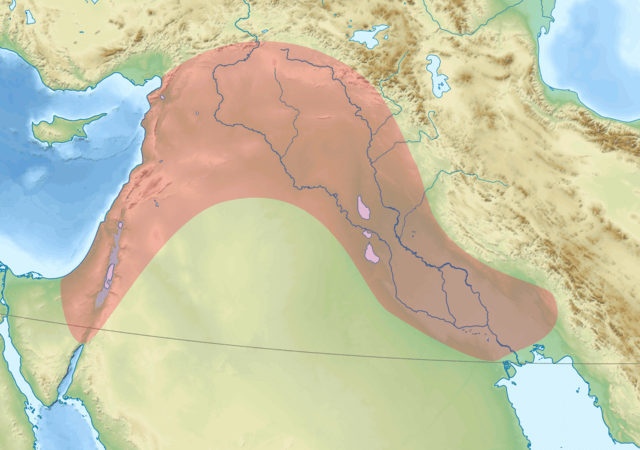

Around 10,000 BCE, the Fertile Crescent in the Middle East is seen as the starting point for farming in the western world when wild grasses were domesticated to produce cereal crops. Descendants of these farmers migrated, eventually appearing in Britain around 4,000 BCE during the Neolithic period. Apart from growing crops, domesticated animals such as cattle and sheep were being kept.

Many improvements were forthcoming over time, some attributable to the Belgic tribes who arrived in Britain in the period before the Romans arrived. For example, the concept of farms appears to be credited to them.

The Romans supplemented their native cultivation expertise by assimilating knowledge from conquered peoples in various parts of their empire. For example, horticulture had originally developed in Egypt around 2,000 BCE. By 1,500 BCE, at the time of Solomon, there is evidence of roses, lily of the valley, saffron, apples, dates, pomegranates, cucumbers, melons, gourds, onion, garlic plus various herbs and spices. Pears and nuts subsequently appeared in Persia around 500 BCE while cabbage, asparagus, seakale, iris and narcissus are thought to be attributable to the Ancient Greeks from around the same period.

The Romans built on all this expertise as their empire grew. For example, at the height of their power there were said to be twenty-two varieties of apple, thirty-six of pear, eight of cherry, four of peach, three of quince, many plums, medlars, grapes, olives and strawberries. They also grew carrot, parsnip, beet, chicory, mustard and collected mushrooms from the woods.

A brief summary of introductions to Britain during the Roman period includes:

- the Romano-British coulter, allowing a range of soils to be ploughed and cultivated, from sandy to heavy loams, gravels, alluvium and clay with flint

- rabbits and new breeds of cattle and sheep during the first and second centuries

- expansion of the existing wool trade, including the establishment of a significant wool factory in Winchester around 50 CE

- mattock, iron spade, iron fork and rake. All the basic hand tools had been invented by this time with the exception of the trowel

- cultivated cherry and raspberry, figs and walnuts

- finally, the Romans are thought to have introduced the concepts of both the orchard and the herb garden.

Religion

Deities and Cults

Celtic religious culture was based on the natural world, where rivers, springs and woods may be venerated, along with the moon, the sun and the stars.

The Roman approach to religion was also polytheistic, that is they honoured multiple deities, which included classical gods such as Jupiter, Juno and Minerva.

As the empire expanded and incorporated new cultures, the Romans were generally content to accommodate additional gods, so long as due deference was paid to their own deities. Better still if local gods could be conflated with Roman gods, an example being Sulis, the Celtic deity, who became associated with Minerva, the Roman goddess.

In addition, there were various cults which sprang up across the empire. The cult of Mithras, which originated in Persia, is one such example. It became popular with soldiers, as it personified courage. Several mithraea, places of worship, have been found in Britain, unsurprisingly near to forts.

The Romans periodically came into conflict with monotheistic faiths, notably Judaism and Christianity, which both insisted that there was only one god, their god. Christians were persecuted on a number of occasions, most infamously by Nero who decided for political purposes to pin the blame on them for the burning of Rome in 64 CE. It was Constantine the Great who eventually legitimised Christianity via the Edict of Milan in 313 CE.

It is unclear when Christianity arrived in Britain, and to what extent it was adopted. There has been much speculation on this subject, although the only evidence appears to be that a British delegation attended the first Church Council which was held at Arles in 314 CE. The Water Newton hoard of silver from the fourth century contains a number of items with inscriptions which leads to the belief that they are early examples of Christian liturgical silver.

Temples

The classical Roman temple was an imposing building which showed how important religion was in Roman culture. They would typically be found in large towns. Remains have been found in Bath and Colchester.

However, in the north-west provinces, the Romano-Celtic temple was the norm. It typically consisted of a box-like cella (inner chamber) surrounded by a veranda, remains of which have been found in Britain at places such as Maiden Castle, Harlow, St. Albans and Caerwent.

Britain and the Empire from the Third Century

This section deals with the decline of the Roman Empire and the effects on Britain. Both had passed their peak by this point. Some of the many power struggles within the empire involved military commanders who were based in Britain, as we shall see. The province itself was to be reorganised twice before the official end of Rome’s occupation in 410 CE.

Apart from the various internal power struggles, the Roman Empire also had to contend with the threats posed by the Germanic and other tribes, such as the Huns, who were intent on moving into Roman territory. This is known as the Migration Period (very roughly 300-700 CE), or more colourfully as the Barbarian Invasion. Reasons for migration included crop failures and a rise in sea levels, notably in the Low Countries. In Britain, there was a major incursion of the Scotti and Picts around the middle of the 4th century, while the Saxons were also periodically starting to try their luck in the south-east.

Britannia Superior and Inferior

Lucius Septimius Severus deposed and killed Didius Julianus who had only been emperor for nine weeks, and then he fought off two rival claimants before donning the imperial purple in 193 CE. Shortly afterwards, he split Britain into two parts, Superior (the stable south) and Inferior (the relatively unstable north). It is not clear precisely where the border between the two lay, possibly along a line between the Mersey and the Wash. Inferior was governed from York by the legate who was in command of the legion that was stationed there.

Severus came to Britain in 208 CE with the intention of conquering the Maeatae and Caledonii but they were too cunning and untrustworthy for him. He died at York in 211 CE and was succeeded by his sons who promptly abandoned the idea of conquest in Scotland.

The Military Anarchy and the Tetrarchy

The period from 235 CE to 284 CE was dominated by many relatively short-lived barracks emperors, that is soldiers who seized power due to their control of the army. Many met violent deaths. Virtually continuous civil war meant that the empire was more vulnerable to attacks from external forces.

Diocletian was another barracks emperor, donning the imperial purple in 284 CE. However, he brought stability to the empire, in part by realising that it needed reorganisation. He split the empire into two. He ruled in the east, while Maximian ruled in the west. In addition, two junior emperors were appointed: Galerius alongside Diocletian; and Chlorus with Maximian. This arrangement became known as the Tetrarchy.

However, it did not necessarily signal the end of trouble. Carausius, a successful commander of the naval fleet in the English Channel, declared himself emperor of Britain and Northern Gaul in 286 CE. He managed to fight off Maximian until he was assassinated in 293 CE by his own finance officer, Allectus, who was himself defeated in battle and murdered in 296 CE when an imperial fleet arrived in Britain. The basilica and forum complex in London was ordered to be destroyed as a punishment for the local support that had been given to Carausius.

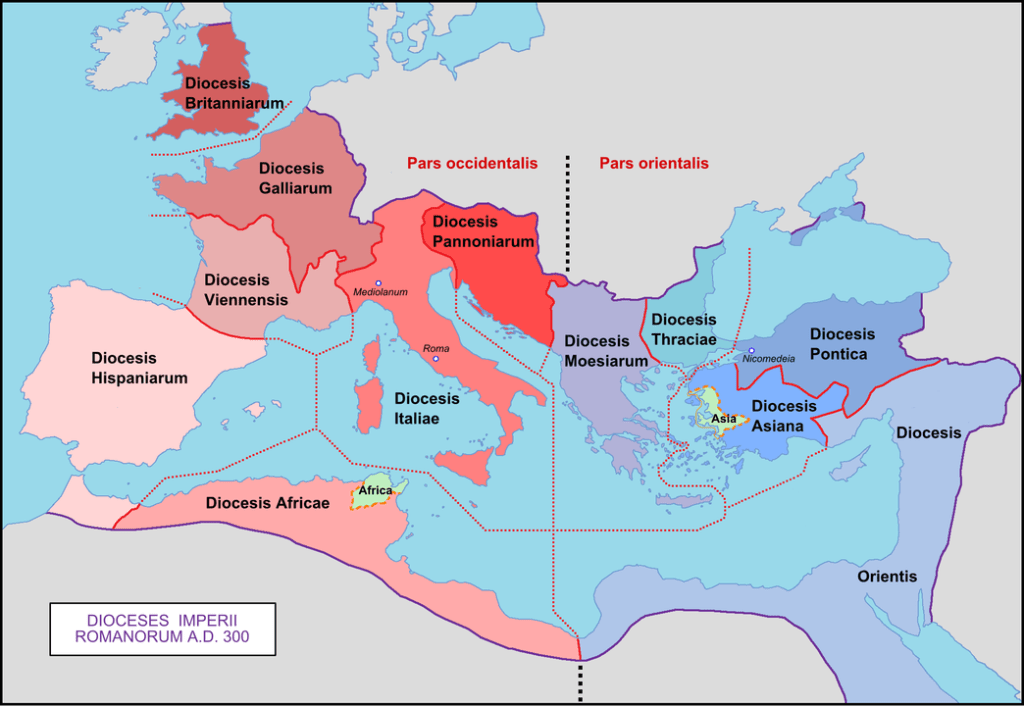

Diocese of Britain

As a further part of his administrative reforms, Diocletian increased the number of provinces, grouping them into dioceses, which was a new administrative layer. A diocese was overseen by a vicarius, from which we get the word vicar.

Britain was converted into a diocese which consisted of four provinces: Maxima Caesariensis (South East and East Anglia – ruled from London); Britannia Prima (Wales, South West and the West Midlands – ruled from Cirencester); Britannia Secunda (the North – ruled from York); and Flavia Caesariensis (North East Midlands and Lincolnshire – ruled from Lincoln).

The governor of the South East, called consularis, was regarded as the senior governor within the diocese, while the others were called praeses. The finance controller was comes sacrarium largitorium. On the military front, dux was in overall charge of the army across the provinces, whereas comes commanded individual parts of the army.

Note that the Christian Church came to use various Roman terms, including the words diocese and vicar that are mentioned above.

The Great Conspiracy

Also called the Barbarian Conspiracy, this was a year-long war (367-368 CE). The Roman forces guarding Hadrian’s Wall rebelled, allowing the Picts to pass through. At the same time, the Scotti landed in the west and the Saxons in the south-east, in what may have been a coordinated attack. The much-reduced Roman force was overwhelmed, particularly in the north and the west, as the invaders went on the rampage, and a number of soldiers deserted. In the south-east, loyal troops stayed in their garrisons.

Flavius Theodosius, a senior military officer and father of the future emperor Theodosius I, was sent to Britain to recover the situation. Initially, he managed to reclaim London, which he then used as a base for his operations, and by the end of 369 CE he had managed to restore the provinces in Britain to the empire. In the process, he created a new province, Valentia, which is thought to have covered the area between Hadrian’s Wall and the Antonine Wall, that is southern Scotland.

The Final Years

In 383 CE, Magnus Maximus, a Roman general who had been assigned to Britain, made his personal move for imperial power. He left for Gaul with his troops, and succeeded in becoming sub-emperor under Theodosius I, ruling both Gaul and Britain.

There was no noticeable Roman presence in north and west Britain after this date. Unsurprisingly, this shortage of troops encouraged the Saxons, Picts and Scotti to make further incursive raids. Magnus Maximus was executed in 388 CE after a failed attempt to go one step further and take the emperor’s purple.

Although Stilicho, a high-ranking general who was effectively acting as a regent for the young Honorius, son of Emperor Theodosius I, subsequently ordered campaigns against the Picts and Scotti in the late 390s, he was under pressure in northern Europe from the encroaching Visigoths and Ostrogoths.

In 406 CE, the Vandals, Suebi and Alans crossed the Rhine and began widespread devastation. The remaining Romans who were present in Britain, fearing that these tribes might cross the Channel, dispensed with imperial authority, deciding to fend for themselves. One of their number, a general called Constantine, eventually took command, and set off with troops for Gaul. Unfortunately, he also had pretensions to grab the title of Western Emperor, but he lost control in 409 CE.

Britain, now without any troops for protection and suffering several Saxon raids, exiled Constantine’s magistrates. A cry for help to the Emperor Honorius in 410 CE was met with a flat rejection, known as the Rescript of Honorius, which effectively told them that they were on their own, as he did not have the necessary military forces to deploy. This was true, as he had his own troubles, being trapped in Ravenna at the time and unable to prevent the Visigoths’ Sack of Rome in the same year. 410 CE is usually given as the official end of the Roman occupation of Britain.

After 410 CE

According to the later historians, Gildas and the Venerable Bede, it is thought that various Germanic tribes began their mass migration into south and east Britain in the 450s. Meanwhile, the fabric of Roman society in Britain gradually disintegrated without a strong government. Roads and towns were not maintained, while trade suffered. In the countryside, the failing economy reduced the market for the products of the villas, which also went into decline and eventually disappeared.

Meanwhile, the Western Roman Empire struggled on as a legal entity until 476 CE, while the Eastern Empire managed to survive in varying forms for a thousand years, during which time it is mostly known to us as the Byzantine Empire. It finally came to an end when the Ottomans took Constantinople in 1453 CE.

Conclusion

In the late Iron Age, Britain was composed of many discrete warring tribes with no national identity. Their inability to make lasting alliances with each other made it easier for the Romans when they invaded.

The south, which already had some exposure to the Roman world through trade links with the near Continent, were more accepting of Romanisation after early uprisings had been put down. This area gradually benefited from the introduction of urban society by their conquerors, along with the new technologies plus the organisational and engineering skills that they brought.

The north, always considered to be a military zone, was a different story. The Romans had some limited success in northern England, but eventually gave up on plans to conquer Scotland.

The benefits which accrued from the Roman occupation peaked during the second century. Thereafter, the slow decline of the empire had its effect on Britain, and the official end of their relationship in 410 CE eventually attracted Germanic tribes to these shores, while at the same time the economy and society deteriorated.

Odds and Sods

Selected Place Names

| Roman Name | Modern Name |

| Londinium | London |

| Camulodonum | Colchester |

| Verulamium | St. Albans |

| Eboracum | York |

| Lindum | Lincoln |

| Wroxeter | Shrewsbury |

| Isca Dumnoniorum | Exeter |

| Glevum | Gloucester |

| Deva | Chester |

| Calleva | Silchester |

| Venta Belgarum | Winchester |

| Corinium Dobunnorum | Cirencester |

A comprehensive list can be found in Wikipedia.

List of Roman place names in Britain – Wikipedia

Legions

There was no standard for naming legions: some used successful campaigns while others used the names of imperial families.

Gradually, increased use was made of vexillations, temporary detachments, nominally consisting of one thousand men, who were dispatched to complete a specified task. This may have been to assist in combating an uprising or to help with a building project.

As the Western Roman Empire began to experience various troubles from the third century, there is little evidence as to the precise military deployments in Britain. At least one source indicates that there may only have been the equivalent of one legion by the fourth century.

The information below is taken from Guy de la Bédoyère’s Roman Britain (p. 207). It can be seen that it primarily deals with the first and second centuries.

The original legions in Britain

II Augusta: Last attested in Notitia Dignitatum in the fourth century. Permanent base: Caerleon.

IX Hispana: At York until at least 107–8 CE. Fate unknown.

XIV Gemina Martia Victrix: Until 70 CE.

XX Valeria Victrix: Until at least the late third century. Fate unknown. Permanent base: Chester.

The replacements

II Adiutrix Pia Fidelis replaces XIV Gemina Martia Victrix from c. 70 to c. 86 CE, then leaves for Dacia.

VI Victrix arrives with Aulus Platorius Nepos, c. 122 CE. Last attested in Notitia Dignitatum. Permanent base: York..

Vexillations from abroad

VII Gemina: Vexillation under Hadrian.

VIII Augusta: Vexillations in the invasion force, and under Hadrian and Antoninus Pius.

XXII Primigenia: Vexillations in Britain under Hadrian, Antoninus Pius, and Caracalla.

Peoples of Scotland

The use of different names for the peoples and tribes in Scotland can be confusing.

The map of the northern peoples of Britain around 150 CE, according to data collected by Ptolemy, shows thirteen tribes to the north of the Antonine Wall. However, most Romans typically called this entire area Caledonia, or the land of the Caledonii.

By the end of the second century, the Maeatae, another confederation of tribes, was being mentioned. The bounds of their territory are unclear, with one view suggesting Clackmannanshire, Fife and Stirlingshire. Moving forward to the late fourth century and the Great Conspiracy, we only hear about the Scotti and the Picts.

Dál Riata was a Gaelic kingdom that covered North East Ireland and West Scotland, which was to reach its heights in the sixth and seventh centuries. Scotti was a Latin name for these Gaels. Meanwhile, the Picts were a group of peoples who lived in Northern and Eastern Scotland, and are assumed to be descendants of the Caledonii and other Iron Age tribes. The area, sometimes called Pictland, was to peak in the late seventh and early eighth century. By 900 CE, Dál Riata and Pictland had merged to form the kingdom of Alba (Scotland).

Coinage

Coins began to appear from the Continent in the 2nd century BCE, principally arising from trade with tribes in Gaul. They had an intrinsic value due to the precious metal content and can be regarded mainly as bullion rather than currency at that time.

Coins began to be minted in Britain in the south. These Celtic coins continued until around the time of Boudica’s rebellion when they were replaced by Roman coinage.

Roman coins were initially only minted in Rome, until they gradually spread to mints in the provinces, in places such as Lyons and Arles. The first mint in Britain was set up in London in 286 CE by Carausius, the usurper.

Coins were periodically debased. The reasons included: inflation, lack of precious metals, and the financial state of the empire (e.g. the need to pay soldiers). The last Roman coins to reach Britain were struck in 402 CE.

Population Size

Although significant work has been carried out by historians to estimate the size of the population, it is all based on a series of assumptions which inevitably means that the results can never be more than speculative. Therefore, take the following as loosely indicative, at best.

In the late Iron Age, improvements in agriculture, coupled with the migration of Belgic peoples from the Continent saw the population possibly increase to circa. 1 million.

By the fourth or fifth century, the advent of the Romans and the explosion of the economy resulted in a peak population of the order of 2.5 to 3 million. With regard to individual town sizes, London’s rose to 40-50 thousand by the end of the second century. The next largest were Cirencester and Colchester, both estimated at around 10 thousand.

After the end of the Roman occupation the population declined rapidly. While the collapse of the economy was undoubtedly a factor, the arrival of the Plague of Justinian in the sixth century is generally accorded significant relevance. It is claimed that 50% of Europe’s population may have succumbed to it. It was to be the Domesday Book in 1086 which indicated that the population had managed to get back to the size that it had been in Roman times.

Slavery

While there is evidence of slavery in Britain before the arrival of the Romans, there had always been a significant demand for slaves within the Roman Empire, and it continued to be so. It is said that they made up between 10% and 20% of the population. Their tasks could vary from extremely hard manual labour in the fields or mines to household chores in the homes of the affluent.

Arguably the main source of slaves came when new territories were conquered, while criminals or individuals in debt provided another source. And of course, children might be born into slavery.

The system allowed a master to free a slave; this process was called manumission. It could be as a reward for loyal service, or so that a master could enter into a legal marriage with a woman. A freedman became a Roman citizen, but the stigma of having been a slave usually stuck with him. For example, Nero sent Polyclitus, his freedman, to carry out a post-mortem after Boudica’s revolt. The Roman administrators in Britain were not happy to have to listen to an ex-slave.

Freedmen are over-represented in surviving texts and funerary inscriptions, given their frequent desire to make a dedication to a deity on behalf of their master, or to tell of their own successful move to Roman citizenship.

Taxation

The Romans developed a complex system of taxation, one that we would recognise today. However, it was a system that was open to corruption, particularly by the tax collectors, which unsurprisingly caused significant resentment. It was one of the grievances which led to Boudica’s revolt. Taxes included:

- land

- agricultural products (crops and livestock)

- customs, e.g. moving agricultural products out of the tribal area

- poll tax

- inheritance tax

- slaves – selling them or freeing them.

Taxes became more onerous from the time of the Tetrarchy when the overheads of protecting the empire’s frontiers grew, while the cessation of expansion brought with it a lack of wealth which would naturally accrue from conquest.

Writing Tablets

The Romans wrote on papyrus and parchment for legal documents, books, histories et cetera. Papyrus had been made from the reed of that name by the Egyptians from around the fourth century BCE, while parchment, made from animal skins, is credited to the King of Pergamum (in modern-day Turkey) in the second century BCE, although it is considered that it had already been in existence for 1,500 or more years.

Papyrus and parchment were relatively time-consuming, and hence expensive to make. For regular day to day communication, wooden tablets were employed. There were two types. The first had a slight depression which was filled with wax. A stylus was then used to write onto the wax. This type of tablet was reusable, simply by heating the wax and allowing it to cool. Over 400 have been unearthed on the site of the Bloomberg building in London. Where the stylus has scratched the wood underneath the wax it has been possible to date them at 50–80 CE.

The other type of wooden tablet was written on with a carbon-based ink. A great number have been found at Vindolanda fort, just south of Hadrian’s Wall. They were made from locally grown birch, alder and oak; they are thin, 0.25 to 0.3 mm thick, and the size of a modern postcard. Dating back to c. 90–105 CE, the content which has been found at Vindolanda includes work rosters and strength reports, along with official and private letters, and even an invitation to a birthday party which had been received by the wife of the fort’s commander.

Note that paper first appeared in China around the third century BCE. Cai Lun subsequently improved the process, and he is officially credited with its invention in the early second century CE. However, it was to be the eleventh century CE before it arrived in Britain.

Sport

The popularity of chariot racing across the empire has already been mentioned, although the only evidence that has so far been uncovered in Britain is in Colchester.

In general, the Romans adapted games that had originally been developed by the Ancient Greeks, notably wrestling, boxing and athletic events such as the pentathlon which comprised jumping or leaping, foot race, discus, throwing a spear and wrestling.