This potted history is dedicated to Peter and Jane O’Kill. Access to Peter’s material on Sunningdale was an initial driver for this piece of writing which complements my article on Sunninghill & Ascot. Further information on Peter and Jane is provided in the Acknowledgements section.

Click on the Contact Me page to send me any comments, ideas for additional material or information on any errors.

Here is the Parish Council’s map of the area if you prefer it to the above Google map.

Contents

Mesolithic, Neolithic and Bronze Ages

The Atrebates, Romans and Saxons

Windsor Forest

The Land

Coworth

Broomhall Nunnery

Turnpikes and Stagecoaches

Major Properties in the 18th and 19th Centuries

The Establishment of Old Sunningdale Village

Churches

Schools

The Railway

Local Government (up to 1894)

Local Government (from 1894)

Village Hall

Coronation Memorial Institute (CMI)

Libraries

Public Houses

Allotments

Sunningdale and District Gardening Association (SADGA)

Sunningdale Golf Club

Sunningdale Bowling Club

Other Sports

Further Residential Development

World War II

Further Growth from the 1970s

Carnival, Festivals and Fetes

Celebrities

Bibliography and Further Reading

Dates. Please note that BCE (Before the Common Era) and CE (Common Era) are used in this article, as opposed to BC and AD.

Introduction

Sunningdale, as we know it, was largely a 19th century creation. Going further back in time, round barrows (burial places) from the Bronze Age provide the earliest evidence of human habitation in this area. Coming forward to the first century BCE, parts of Berkshire and Hampshire were populated by the Atrebates, a Belgic tribe, who became friendly with the Romans before the latter’s invasion of Britain. The Roman London to Silchester road, built soon after the Roman arrival, passed through this area.

After the Romans left these shores, it is claimed that the tribe of a Saxon chieftain, Sunna, which was based in Sonning, was responsible for giving Sunninghill, Sunningdale, and possibly Sunbury, their names.

Broomhall Nunnery is next to come into view. Founded in 1157, it lasted until 1522, during which time we start to hear about Coworth and its owners. As time marches on, other properties and their owners gradually come to light in the following centuries, including Sunningdale Park in the late 18th century. Up to this point, the area was very sparsely populated, not helped by the very poor soil which was not likely to attract many individuals in our agrarian society.

It was in the early and mid-19th century that the core village of Sunningdale finally began to take shape, primarily based around the church of Holy Trinity. Improvements in transport, first with the arrival of the railway and more recently with the motorway system, have led to population growth and the establishment of the improved infrastructure that is necessary to support life in the 20th and 21st centuries. The latest Census in 2021 puts the population of Sunningdale at 5,636.

The following slideshow displays drawings from Sunningdale’s Millennium Calendar.

Before Sunningdale

This section summarises the limited information that is available on the area from pre-history through to the early 19th century.

Mesolithic, Neolithic and Bronze Ages

While evidence has been found of human existence during the Mesolithic and Neolithic Ages across Berkshire and Surrey, notably flint-based tools, none has so far been found in Sunningdale. The nearest finds have been unearthed at Silwood Park, Cheapside and at various places on Chobham Common.

Coming forward to the Bronze Age (2300 – 800 BCE), burial mounds, often called round barrows, are a relatively common feature. One was opened up south of the Sunningdale Golf Club’s clubhouse in 1901. It contained twenty-three cinerary urns and two cremated interments without urns. Seven of the urns are in Reading Museum and one plus fragments in Guildford Museum. There is another small barrow nearby, which has not been excavated. Other barrows have been located in Ascot and on Chobham Common.

The Atrebates, Romans and Saxons

From around the end of the Bronze Age, a number of Celtic tribes began to migrate from the Continent to southern England. The Atrebates, originally from the Artois region of Northern France, settled in Northern Hampshire and parts of Berkshire, and eventually made Calleva their capital. It was subsequently called Silchester and can be found just south of Reading. They had already established friendly relations with the Romans before the latter’s invasion of Britain, and had benefited from knowledge of their advances in civilisation. Significant information on Calleva can be found in Reading Museum.

The London section of the Roman London to Silchester road is estimated to have begun construction in 47 or 48 CE. It was subsequently named “The Devil’s Highway” by the Saxons who could not believe that men could have built such a straight road. It passed through the Sunningdale area, along the edge of Broomhall Farm next to the allotments, through Broomhall Recreation Ground and then ran parallel to the A30, crossing Devenish Road just to the north of it.

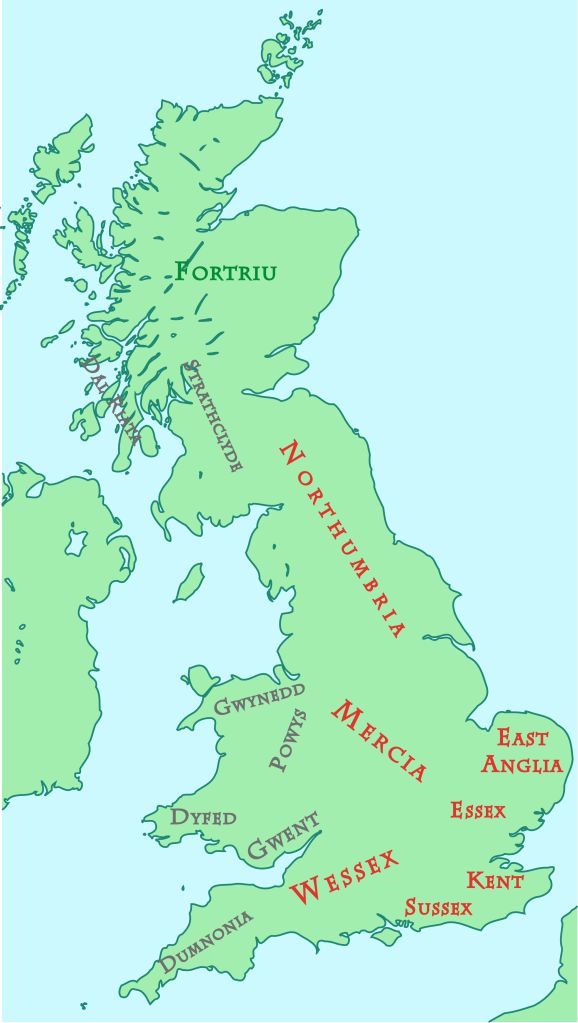

After the Romans left Britain in the early 5th century CE, various Germanic tribes arrived and settled, the Angles, Saxons and Jutes. The country very gradually coalesced into a Heptarchy, that is seven discrete kingdoms (shown in red on the map). Continual fighting between them meant that borders were fluid. East Berkshire was principally part of the kingdom of Wessex, although it also spent some time as part of Mercia, not forgetting periods when the Vikings were running the show.

The first King of England was Æthelstan, King of Wessex and grandson of Alfred the Great, who was crowned in 924 CE. The Anglo Saxon dynasty had a palace in Old Windsor until William the Conqueror built the castle up the road in Windsor.

The manor of Old Windsor, which included the Sunningdale area, was granted by Edward the Confessor to the Abbot of Westminster Abbey in 1066 just before the king’s death, although William the Conqueror reverted it to the Crown shortly afterwards.

Windsor Forest

William was responsible for the creation of Windsor Forest, after he had identified that the area was good for hunting. Forests at that time were not necessarily an indication of totally wooded areas. They tended to define enclosed areas. Windsor Forest was significantly larger than it is today, possibly going as far west as Basingstoke and Reading. However, Hughes is confident that it did not stretch into Surrey. The king may well have hunted in parts of Surrey, but they were not legally part of Windsor Forest.

The Land

Sunningdale is on the edge of Chobham and Bagshot Commons to the south and west, and Windsor Forest to the north. The soil is generally poor. One description of the land in the parish of Old Windsor indicates that only 5% of it was suitable arable land.

This is due to the Bagshot Sand, a geological feature which indicates that 50-60 million years ago when the sea retreated, a huge sandbank was left, sitting on top of the London Clay. Centred on Bagshot, it measures approximately 20-25 miles from east to west and 10-12 miles north to south. Views from the train, particularly between Virginia Water and Sunningdale, show a somewhat dreary, colourless landscape filled with the likes of heather and broom (except of course for Wentworth Golf Course!).

Coworth

Coworth was one of two places of note in this area. Hodder states that it had previously been called “Herdies” in a grant of land to Chertsey Abbey. He associates it with the Angles who had settled in Anglefield (Engelfield). They were followed by the Saxons who found good grazing land, particularly around Thornihull (Shrubs Hill) and came to call the area “Cow Garth”.

By the middle of the 14th century, there is evidence of a small hamlet around Blacknest. Coworth was a significantly larger area at the time, and it was mainly dominated for the best part of four centuries by two families, first the Darenfords, and subsequently the Lanes.

Broomhall Nunnery

This nunnery was the other place of note in the area. Hughes states that the church of St. Michael’s and All Angels in Sunninghill dates back to 890. In 1199, King John granted the advowson (or patronage) of St. Michael’s to the Priory of St. Margaret at Broomhall, an indication that Sunninghill was a relatively unimportant place. The Priory was itself a daughter-house of the Benedictine Abbey at Chertsey, and in fact the priests at Chertsey were responsible for the services at St. Michael’s and All Angels up to 1297.

This Priory for Benedictine nuns, which was first mentioned in 1157, had been founded by Isabel De Warenne. The De Warennes were Norman earls of Surrey. The Priory was a modest wooden construction, and nothing remains of the building which is thought to have been sited close to Broomhall Farmhouse.

It was only a small institution with a Prioress and six or seven nuns. It enjoyed some royal patronage, particularly during the 13th century, when it was granted various pieces of land in Egham, Chertsey, Chobham, Winkfield, Sunninghill and Bagshot. However, its fortunes eventually waned, as did many monastic institutions after the Black Death in the 14th century, and the Priory was dissolved after various troubles in 1522. All its possessions and advowsons were eventually granted to St. John’s College, Cambridge.

Broomhall was subsequently leased to various individuals, some active farmers and others who might be described as gentlemen farmers. The College itself also ran it for a time. Broom Hall, the property that went with the farm, was rebuilt in the early 17th century.

Turnpikes and Stagecoaches

The poor state of the roads in England, particularly the main roads out from London to other towns and cities, began to affect the transportation of goods in the country’s growing economy. This ultimately led to the erection of turnpikes from around the beginning of the 18th century.

The resultant road system was not centrally planned. It was based on local enterprise. Bodies of local trustees, regulated by Acts of Parliament, were given powers to levy tolls on users of a turnpike, a stretch of road which was usually 15 to 20 miles in length, with the income being used to maintain and improve the road. These trusts remained responsible for the majority of England’s trunk roads through to the 1870s.

The Egham and Bagshot Trust was established in 1727 with responsibility for a toll road which ran from Powder Lane in Hounslow to the Golden Farmer in Basingstone (Bagshot), part of the today’s A30. The Golden Farmer, subsequently the Jolly Farmer, is currently an American Golf Store. Major coaching inns were to be found at Egham and Bagshot, both places growing and prospering because of the stagecoach business.

It became a busy road, ultimately taking traffic from London to Portsmouth and Southampton. The Royal Navy, who transported gunpowder and other materials, and mail coaches were particularly heavy users of this road which passed through Sunningdale. There is some evidence that the Broomhall Hutt, originally called Chequers, was in business as an inn next to the road from the 1770s, possibly earlier.

In 1784 a new fast mail coach service from London to Bagshot was started with an armed guard. This generally barren area with relatively few inhabitants had always attracted robbers, and it is probably reasonable to say that the golden age of highwaymen in England began in the 1660s, around the time of the Restoration of the Monarchy, and lasted until the end of the 18th century. William Davis (based at the Golden Farmer), Claude Duval, Captain Snow (based at the Pelican on Snow’s Ride) and Parson Darby are thought to have operated in this area.

The Windsor Forest Trust was formed in 1759 to create a 17-mile turnpike road from the Gallows Inn in Reading, through Wokingham, Bracknell, Sunninghill, and on to “a rivulet called Virginia Water”. This is today’s A329.

The Wheatsheaf Hotel on the A30 in Virginia Water was established as a turnpike inn in 1768, from where it could handle trade from both turnpikes.

Hodder says that at the beginning of the 19th century, it cost 12 shillings and sixpence to travel outside (on top of the coach) from the Wheatsheaf to London. This is the equivalent of £35-40 in 2024. To travel in comfort inside the coach was one guinea. These were obviously sums of money that were way beyond the pockets of most people, with the exception of the gentry. The relative ease of travel to and from London via toll roads undoubtedly attracted them to this area where they were able build large properties.

Major Properties of the 18th and 19th Centuries

It was not uncommon for the gentry to spend the summer here and the winter back in London. Here are some of the larger properties in the area that were developed from the 18th century onwards.

Fort Belvedere, initially called Shrub’s Hill Tower and strictly speaking in the parish of Egham, was built in the early 1750s for the Duke of Cumberland, the younger son of George II. It was subsequently occupied by members of the British royal family and associated individuals, and in fact it was used by Edward VIII before he became king and for signing the instruments of his abdication in 1936.

Coworth House was constructed in 1776 by William Shepheard, a wealthy East India merchant with offices in London. It subsequently had various owners, including the Earl of Derby and his family, before being converted into a commercial enterprise in the 1980s.

The first house on the Sunningdale Park estate dates back to circa. 1786 and was probably built for James William Steuart, a gentleman farmer and the grandson of Admiral James Steuart. Northcote House, the current property on the site, was completed in 1930/31. In more recent times, Sunningdale Park has served as the Civil Defence College (1950-1968) and as the Civil Service College (1970–2012).

Tittenhurst Park was originally built in 1739. From 1869, it was owned by Thomas Holloway, the philanthropist who built Royal Holloway College, now part of the University of London.

Broomfield Hall was probably built in the 1830s or 1840s. It was subsequently purchased in 1869 by Thomas Holloway who started significant extension work until he changed his mind and bought Tittenhurst Park instead. The work was continued by James Reiss Esq, the new owner.

Lynwood, which straddles Sunninghill and Sunningdale, dates from around the same time. The original owner was John Hargreaves who sold it to Admiral Sir Frederick William Grey in 1864. He was a son of the second Earl Grey who had been a Whig (Liberal) Prime Minister in the early 1830s. It was his father who received a gift of tea, flavoured with bergamot oil, which subsequently became known as Earl Grey.

Shrubbs Hill Place was another 19th century mansion. Owners in the late part of that century included John Torry Esq. and George Walmsley Esq.

Wardour Lodge at the bottom of Rise Road dates back to the middle of the 1860s. It is currently divided up into a number of flats.

Finally, Charters House was built in the late 1860s for Frank Parkinson, an industrialist, and rebuilt on the same site in 1938. It was subsequently purchased by Montague Burton, the retailer, in 1949. The estate, which also straddled Sunninghill and Sunningdale, was over 100 acres in size.

Early Sunningdale

Sunningdale slowly began to take shape from the 1820s through to 1894 when it became a Civil Parish.

The Establishment of Old Sunningdale Village

By the end of the 18th century there was just a smattering of cottages for agricultural and domestic workers on the large estates around the southern end of Windsor Forest in SunninghillDale, as it was known.

The initial driver for the expansion of the area was the enclosure of land. The Windsor Forest Enclosure Act of 1813 was one of many acts which enclosed over 5 million acres of land across the country, principally in the 18th and early 19th centuries. It took until 1817 to sort out the various claims which arose from the Windsor Forest Act. Other contributing growth factors were the building of a parish church and the arrival of the railway in 1856.

Early buildings on Sunningdale High Street included a Baptist Church in 1828, along with a couple of properties and the Nags Head public house. Holy Trinity Church was consecrated in 1840 and officially became the ecclesiastical parish church of Sunningdale in the following year while properties in Station Road around this time included the Old Dairy and Magnolia House.

The remainder of the 19th century saw the development of larger properties along Church Road, previously known as King’s Beech Road, including the National School at the opposite end to the church (1842), the vicarage (1847) and a row of cottages along Whitmore Lane. Trinity Crescent, running from Church Road to High Street alongside the church, was not developed until the 1930s.

The Old Village was made a conservation area in 1995, as illustrated by the following map (possibly not visible on tablets and phones). It is one of twenty-seven such areas in the Royal Borough of Windsor and Maidenhead. To download the map, click on the button beneath it. Use the zoom feature on your device when displaying the downloaded file to identify individual street and house names. This 7-page appraisal of the area, also on the RBWM website, provides further detailed information.

Churches

Legislation in the 1820s, most notably the Catholic Emancipation Act of 1829, removed some of the barriers which had excluded Christians outside the Church of England from many public offices. This ultimately led to a period when there was much competition between the various faiths to build churches, as they fought to attract worshippers.

As stated, the Baptist Chapel was the first to appear in Sunningdale High Street in 1828.

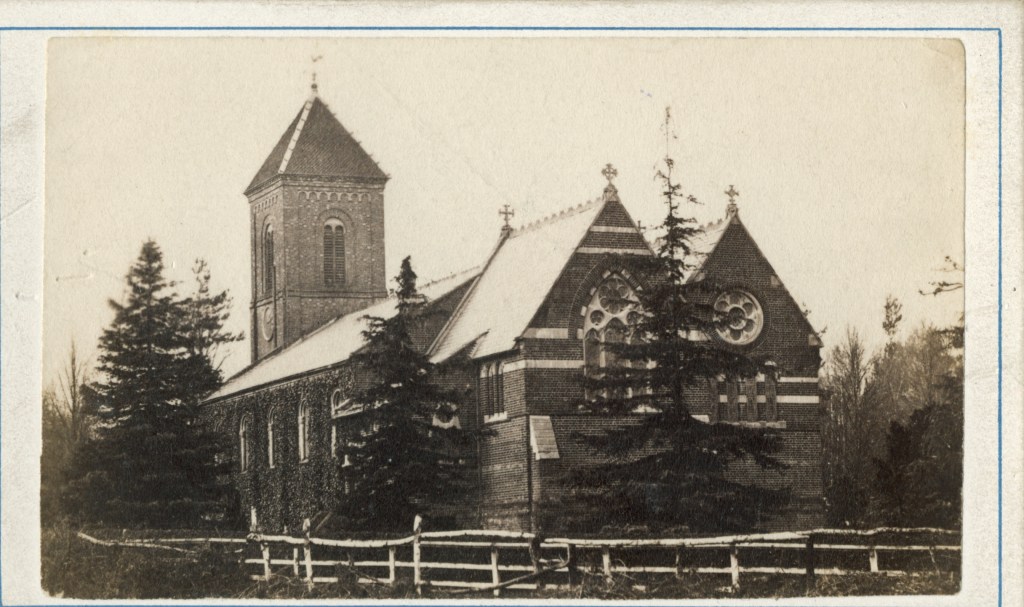

The local population was of the order of 600 to 700 by the late 1830s, and it was considered appropriate that Sunningdale should have its own Church of England place of worship. Holy Trinity was built on a large gravel pit, the contents of which the military had previously used to build roads.

The army had been much in evidence in this part of the country due to concerns about Jacobite uprisings in the 18th century and French wars in the early 19th century. Soldiers were also responsible for digging out the original Virginia Water Lake, which is a man-made construction, from 1746. After a flood in 1768, a larger lake was constructed from 1780.

Holy Trinity was consecrated in 1840 and officially became the ecclesiastical church of Sunningdale in the following year. It was initially a relatively plain church. However, in 1860 the Reverend William Raffles Flint oversaw the redevelopment of the Chancel and the addition of a small chapel. And in 1887, with an increasing population, the Nave was rebuilt and the spire was extended with funds provided by William Farmer at Coworth Park.

Other churches which no longer exist comprise: the Congregation Church on High Street which was founded in 1865; a Methodist Church (foundation stone laid in 1891), and the small chapels of St Agnes in North End on the south side of the A30 (pre-1914) and St Alban (1911) although the latter was technically in Windlesham.

Coming forward in time, the Sacred Heart church off the A30 serves the Roman Catholic community. It is run by the Verona Fathers, part of the Comboni Missionaries which were established in Italy in 1867. They purchased Shrubbs Hill Place in 1938 for use as a seminary. However, the war intervened. Being Italians, they were interned for the duration of the conflict on the Isle of Man. The building was eventually returned to them in late 1947, acting as a seminary from then on, as originally intended. The church itself was consecrated in 1964 and completed in 1966.

Schools

It was to be 1870 before the UK Government got involved in the field of education when its first Education Act came into force. Before that time there were various attempts to teach literacy:

- In the late 18th century, Sunday Schools were one of the earliest attempts to teach children and some adults to read and write

- Ragged schools then appeared, teaching in unlikely places such as lofts, stables and even under railway arches. One of the last ragged schools, which were formally abolished in 1902, was Doctor Barnado’s in Tower Hamlets

- Going back to the early 19th century, two “monitorial” systems came into existence, both methods making up for the shortage of teachers by getting some of the older pupils to act as helpers

- Yet another approach was the dame school, where a local woman (or retired soldier) would teach a couple of children to read and write for a small fee. There were two dame schools in the Sunningdale area, one of them in Shrubs Hill.

Doctor Andrew Bell had adapted the monitorial system, calling his version Madras. The National Society for Promoting Religious Education was formed in 1811, and it used Bell’s system, although it based it on the teachings of the Church of England. The idea was that a school would be sited next to the church and would be called a National School. Holy Trinity School was established in 1842, albeit at the other end of Church Road.

Independent schools for people of means became particularly popular during the late 19th and early 20th century, and Sunninghill and Ascot attracted a significant number of these schools. Locally, Sunningdale School was founded in 1874 by Canon William Girdlestone, initially accommodating 30 boys. A chapel was added in 1880.

Moving forward to the mid-20th century, Charters Secondary Modern School was opened in the late 1950s on land that had been part of the Charters estate.

Finally, Sunningdale Pre-School was originally founded in 1969 as the Sunningdale Playgroup, using the Village Hall. It currently uses the Small Hall in this building which was built in 1989.

The Railway

Extending out from London, the railway had reached Staines by 1848 and construction by the Windsor, Staines and South Western Railway Company continued towards Datchet, and ultimately to Windsor. However, the Staines, Wokingham and Woking Railway Company received authority to commence work on a line from Staines to Wokingham in 1853.

It goes in a large curve between Virginia Water and Sunningdale because Colonel Colloner, the owner of Portnall Park (part of the Wentworth estate), made strenuous efforts to prevent the line from going across his land. Anyway, the railway reached Sunningdale and Ascot on June 4th, 1856.

The station has had various name changes over the years: Sunningdale and Bagshot (1863); Sunningdale (1878) after Bagshot Station was opened; Sunningdale and Windlesham (1893); Sunningdale for Windlesham (1920/21); and eventually back to Sunningdale.

The history of Sunningdale Golf Club indicates that trains did not stop at Sunningdale in 1901. This is obviously not true, although it may possibly have been the case that not all trains stopped there at the time.

The arrival of the railway helped to encourage the growth of garden nurseries that initially found business with the larger properties in the area, providing jobs for some of the locals.

Local Government (up to 1894)

The Church Vestry had gradually evolved by the late 17th century into the face of local government in England and Wales, such as it was. It was a committee for the secular and ecclesiastical government of a parish, which met in the vestry of a parish church, hence the name. Its responsibilities included: law and order, administration of the Poor Law and the policing of the wastes (poor common land) to prevent unauthorised use.

Soldiers returning from the Napoleonic Wars significantly increased the pressure on the existing Poor Relief system. This state of affairs led to the Poor Law Amendment Act (1834) which introduced Poor Law Unions, larger establishments that were run by appointed boards of guardians who were responsible for the administration and funding of Poor Law Relief. These unions subsequently took on other duties such as civil registration (births, deaths, marriages, et cetera).

Sunningdale was part of Old Windsor, and therefore its matters were dealt with by the Church Vestry at Old Windsor and by the Windsor Poor Law Union. The Windsor Workhouse (built in 1839-1840) is the current King Edward VII hospital.

These unions also provided the geographical and administrative basis for Rural Sanitary Districts that were set up in 1875 to improve public health. They logically followed on from the various cholera outbreaks in Victorian Britain that were due to unclean water and which had led to the appointment of Medical Officers of Health in major conurbations.

Finally, County Councils came into existence in 1888. As part of their remit, they took on the responsibility for the roads that had been managed by the turnpike trusts. The Windsor Forest Trust had expired in 1868 and the Egham and Bagshot Trust in 1877.

Maturing Sunningdale

The establishment of the Parish Council in 1894 saw the start of Sunningdale’s expansion, both in area size, population and social structure.

Local Government (from 1894)

The Local Government Act (1894) specified that any parish with a population of 300 or more should have a council. Sunningdale’s population exceeded this figure, by the turn of the century it was thought to be around 1,400, and so Sunningdale Parish Council was formed.

The law stated that the first meeting of these Parish Councils had to take place before the end of 1894. Sunningdale cut it fine, holding its inaugural meeting on December 31st under the chairmanship of the Reverend Cree of Holy Trinity.

The 1894 act also saw the creation of Urban and Rural Districts which replaced the Sanitary Districts. Sunningdale became part of Windsor Rural District Council.

Poor Law Unions were finally abolished in 1930 when the responsibility for public assistance was passed to County Councils and County Borough Councils.

Bringing the picture up to date, the Local Government Act (1972) saw the abolition of the Rural District in 1974 when this area became part of Windsor and Maidenhead, one of six boroughs in Berkshire. Eventually, Windsor & Maidenhead became a unitary authority when Berkshire County Council was abolished in 1998.

Finally, Sunningdale had been part of two counties. The Old Village and surrounding areas were in Berkshire, while other parts, notably those on the south side of the A30 were in Surrey. It was not until 1995 that Sunningdale was declared to be wholly within Berkshire.

The Village Hall

The Parish Council had approached St. John’s College in 1897 about a site for a Village Hall which was to be erected in commemoration of Queen Victoria’s 60th anniversary on the throne.

However, the College was not prepared to fund it, and it was to be 1908 before any progress was made when a local architect, T. Leonard Roberts, presented detailed plans for the Hall and Henry Alexander Trotter, a wealthy stockbroker who had recently settled in King’s Beeches, agreed to fund it in memory of his father.

Mr Fedder, an allotment holder, arrived one day in 1909 to work his plot, only to discover that they had started building the Village Hall on it. He, and other plot holders who were similarly affected, were each paid £1 in compensation.

The Hall was used for the first time by the Debating Society on December 4th, 1909. There does not appear to have been a formal opening ceremony, but by the end of January 1910 there were a variety of events that were taking place in the Hall.

The history of the Village Hall in more recent times has been dominated by changes in management along with constant repairs and improvements to the building, the latter including the addition of the Small Hall, a porch and the car park at the rear.

The trustees were chaired by the vicar of Holy Trinity until 1984; a secular management team then ran the show until 2009; followed by a joint Parish Council / Church set up until 2023. The current arrangement sees the Parish Council acting as managers with four independent trustees. See the Charity Commission entry for further information.

In return for planning permission in 1989 to build three large detached houses on an adjoining one acre site, St. John’s College granted the freehold of the Village Hall and the allotment site to the Parish Council.

From 2009, Village Venues, originally set up to act as a Community Hub, became responsible for managing the bookings for both the Village Hall and the CMI building. Currently, the Parish Council employs a team to manage the marketing, bookings and maintenance of the Village Hall.

Coronation Memorial Institute (CMI)

Working Men’s Colleges appeared from around the middle of the 19th century, their main objective being education. They were only partially successful, and Working Men’s Clubs and Institutes, founded in 1862, proved more popular with their availability of games such as billiards, darts and draughts, complementing a reading room with books and newspapers.

A couple of iron huts were initially deployed on the opposite side of Church Road from Holy Trinity from 1893 for use as a Club and Institute. The Coronation Memorial Institute (CMI) was subsequently opened here in 1912 as a belated commemoration of the coronation of George V. It is said that there were eventually some 3,000 books at Sunningdale.

The Social Club, as it became known, ceased to exist in 2004. The building has undergone various uses over recent times, including the church-based Community Centre. It is currently being used in 2024 as a nursery / pre-school.

Libraries

As mentioned above, it is claimed that the Working Men’s Club and Institute in the CMI building housed an estimated 3,000 books.

There appears to be no mention of any other library in Sunningdale until the arrival of RBWM’s Mobile Container Library which sat in the Parish Council car park for a couple of days each week. It was eventually replaced in 2022 by a “pop up” library in the Community Room at the Pavilion, which was funded by the Parish Council in partnership with RBWM. It is open on Fridays, Saturdays and Sundays.

Across the UK, people began to convert telephone boxes into micro-libraries where people could take and bring books as they wish without any bureaucracy. The first was set up in Westbury-sub-Mendip in Somerset in 2009 after the local council cut funding for the area’s mobile library in the village. It was in 2015 that Sunningdale Parish Council set up the telephone book exchange facility in Chobham Road.

Public Houses

Local establishments have included:

- Chequers on the A30, now the Broomhall Hutt (1770s, possibly earlier)

- Nags Head on the High Street (1828)

- Royal Oak on Station Road (1881-2021)

- Sunningdale Hotel also known as the Station Hotel or the Railway Hotel (1877-1930?)

- White Lion (1881- ?).

Here are a number of “Then and Now” pictures. The old pictures were provided by John End and the recent pictures by Peter O’Kill.

Allotments

Land enclosures resulted in a clamour for allotments, initially in rural areas during the 18th century where they could be up to two acres in size, and later in more urban areas where ten poles (250 square metres) became the standard size for allotment gardens, as they were called.

Clarefield Court, next to the Majestic Winestore, is shown on an 1861 estate map of St. John’s College as allotment gardens (the red place marker on the map below). The site lasted until around 1890 when the College built this property, which was initially occupied by its local agent, Robert Keirle.

Meanwhile, the Reverend William Raffles Flint had come to an agreement with the College Bursar sometime around 1880 to rent the field adjoining Church Road and Station Road, which he let as allotments (the blue place marker). When the Parish Council became responsible for these allotments in 1895, the site occupied in excess of seven acres, including what is now the school playing field. Its current size is approximately 2.6 acres.

Briefly, there was a third allotment site. St. John’s College let a small piece of land on Chobham Road, just past what is now Richmond Wood on the way to Chobham (the green place marker). There were at least 8 plots there from 1896, possibly earlier, up to 1932 when the site was leased out for development.

Sunningdale and District Gardening Association (SADGA)

The Royal Horticultural Society (RHS) started life as the Horticultural Society of London in 1804. The initial chairman was John Wedgwood, son of Josiah Wedgwood, while the celebrated botanist Sir Joseph Banks was also present at the initial meeting to discuss the idea of a society. It subsequently acquired its present name by royal charter in 1861.

Societies were springing up elsewhere across the country during the 19th century. The concept of affiliated societies goes back to at least 1858 when the idea of “unions” between London and provincial societies was first mooted. However, it was 1865 before the first tentative unions came into existence.

The Ascot, Sunninghill & District Horticultural Society was founded in 1884, holding its first show at the racecourse in the same year. This show was primarily aimed at professional gardeners with sections for amateurs and cottagers. Sunningdale was included in the title in 1889.

After early enthusiasm, there were periods from 1900 through to 1919 when the society verged on extinction. Happily, it got going again in 1919 when Dr. Herbert Crouch led preparations for a summer show, featuring vegetables, fruit and flowers, and it became affiliated to the RHS in the following year.

Sunningdale eventually formed its own society in 1936, although it was still primarily aimed at professional gardeners until after World War II. Meetings were held at the CMI until the 1970s, then in the original WI Hut (not the current building) and finally in the Village Hall.

Unfortunately, SADGA (Sunningdale and District Gardening Association) went out of existence at the end of 2018.

Sunningdale Golf Club

The modern game of golf is generally considered to have had Scottish origins, dating back to the 15th century. The first course in England was at Blackheath where Henry, the son of James VI of Scotland and I of England, played with other courtiers in the early 17th century. However, it was 1864 before the next course was built in England at Westward Ho. There were eventually 12 courses in 1880, 50 by 1887 and over 1,000 by 1914. Ascot had a course in the middle of the racetrack in 1887.

Brothers T.A and G.A Roberts built a house called “Ridgemount” in 1899, and then approached St. John’s College with a plan to build an 18-hole golf course on the land. An attraction for the College was that the idea to create leaseholds on adjoining land for the building of quality homes.

The golf club itself was founded in 1900. In 1911 a separate 9-hole course was constructed on Titlarks Hill Farm, which was subsequently converted into an 18-hole course in 1923.

Sunningdale Bowling Club

The club started life in 1912 off Halfpenny Lane (Clarefield Court presumably), but only for one season. The vicar of Holy Trinity then offered part of his garden, where they played until 1920. At this point the club managed to find new accommodation in Whitmore Lane, where they have remained ever since.

Other Sports

There was a single tennis court next to the bowling green off Halfpenny Lane in 1912, although it has not been possible to find out how long it was there. The Parish Council eventually built four tennis courts on the Broomhall Recreation Ground after World War II.

There is the very occasional mention of football, but nothing that seems to indicate the presence of an established, affiliated club that played in any league.

Further Residential Development

Developments have included:

- Building on and around Rise Road from around the middle of the 19th century, including Beech Hill Road. Mary, the widow of Major Joicey, the owner of Sunningdale Park, subsequently built twelve cottages on Rise Road in memory of her husband after his death in 1912.

- Along with the Ridgemount company, who were mentioned in connection with the golf club, the College constructed Ridgemount Road (1909-10). This was followed by further new roads: Titlarks Hill and Lady Margaret (1910-13) and Priory Road (1928-29).

- Broomfield Hall was demolished in the early 1930s and the Broomfield Park development was commenced on the site.

- The Charters estate was split up in the late 1950s when the house and 16 acres of land was sold to Vickers Research; 13+ acres was the subject of a compulsory purchase order to accommodate Charters Secondary Modern school; and the development of Sunning Avenue began in the early 1960s, followed by Hancock’s Mount and Cavendish Meads which are both technically part of Sunninghill.

- The Redwood Drive / Lawson Way development in Shrubs Hill took place in 1983/4 on land sold off by the Comboni Missionaries (Verona Fathers).

- Most recently, the Sunningdale Park development of houses and apartments, set in 47 acres, has commenced. At the time of writing, May 2024, it has yet to be completed.

On the business front, Broomhall Buildings which straddles the corner of Chobham Road and the A30 was developed in the early 1930s. See the “Then and Now” pictures.

World War II

The outbreak of war led to the mass evacuation of schoolchildren from London. It is estimated that over 1,300 children came to Ascot and the Sunnings. The infants at Holy Trinity School were moved to the CMI building, while their school was occupied by St. Saviour’s school, Poplar.

Although Sunningdale was well away from the devastation that was heaped on London, particularly in the East End, there were occasional instances of bombs and other explosives being dropped locally. They included: bombs dropped on Coworth Park, Sunningdale golf course and the bowling club; a deliveryman killed by a bomb near Sunningdale station; and a large crater appearing in Blacknest Road.

The War Memorial, which had originally been unveiled in 1922 with details of the fallen in World War I, was updated to include the victims from the second conflict. It can be found on the Eastern corner of the churchyard at the junction of Church Road and the High Street.

Further Growth from the 1970s

Rapid economic growth, particularly in the field of Information Technology, coupled with greater use of the car and the advent of the motorway system, attracted many companies to the Thames Valley area, which in turn brought increases in the local population. Sunningdale’s population was 4,875 in the 2001 Census, 5,347 in 2011 to 5,636 in 2021.

One notable growth area across Ascot and the Sunnings has been the establishment of retirement “villages” and care homes. Audley Village (part of Sunningdale Park), Lynwood and Clarefield Court are sites that we have previously come across in this history. While dotted along the A30 are The Ambassador and Stone Court.

Local Organisations

A significant number of organisations and clubs have been established in Sunningdale over the years, many of them having charitable status. Instead of mentioning items from the ever-changing list, it is recommended that you look at the Parish Council’s local organisations webpage for further information.

Carnival, Festivals and Fetes

This type of event has been more prominent in recent years in this area.

The Sunningdale Area Carnival, organised by an independent committee, was first held in 1977, the year of Queen Elizabeth II’s Silver Jubilee, with the aid of public funds that had been made available to allow communities to celebrate. It then became an annual event, held initially during the late May Bank Holiday before moving to September. Themes were introduced, including “Around the World in Eighty Days” in 2010. Stalls, rides, games et cetera were mostly run by local groups such as the brownies and scouts, along with some by local businesses, all sited at Broomhall Recreation Ground. Any profits were distributed among local worthy causes. The last carnival took place in 2015. It has recently been succeeded by Party in the Park.

In 2009 and 2010, the Parish Council and Holy Trinity Church organised Party round the Parish, a weeklong series of events which included the Area Carnival itself. Other ad hoc events have included a very popular music festival in 2012 and Holy Trinity’s Summer Festival in 2019.

And lastly, both Holy Trinity Primary School and Charters School have had their own summer events in recent years.

Celebrities

Finally, Sunningdale is a pleasant area to live, and it has attracted various stars over the years, although possibly not quite as many as some estate agent advertisements might lead you to believe.

Celebrities who have lived here over the years include: Agatha Christie (in the 1920s); Diana Dors (the actress); John Lennon followed by Ringo Starr at Tittenhurst Park; Alan Titchmarsh (the gardener, author and presenter) in Beech Hill Road in the days before he became famous – he was also a plot holder at the allotments; Cliff Richard on part of the Charters estate; Andy Murray (the tennis player) near the golf club; and Sophie Christiansen (the Paralympic equestrian rider).

Bibliography and Further Reading

Primary Sources

Peter O’Kill’s research notes on Sunningdale

Hodder, F.C., A Short History of Sunningdale, Takahe Publishing Ltd, Coventry, 2011

Herbert, S., The Charters Story, De Beers Industrial Diamond Division

Morris, R., Images of England Around Ascot, Tempus Publishing Ltd, Stroud, 2000

The Royal Berkshire Archives in Reading (previously known as the Berkshire Record Office) contain items relevant to Sunningdale, including (but not limited to) material relating to the Civil Parish and to the Village Hall. You can search their online catalogue in the first instance to see what they hold.

Ancient Site Database

British History Online: Parish of Old Windsor

Entry on Sunningdale in Kelly’s Directory of Berkshire (1899)

RBWM map of Sunningdale Conservation Area

Appraisal of the Sunningdale Conservation Area

History of Holy Trinity Sunningdale

Peter O’Kill: A Brief History of Sunningdale

Peter O’Kill: History of Sunningdale Village Hall

Peter O’Kill: Abridged History of SADGA

Bob and Betty Montgomery, Peter O’Kill and Hugh Devonald: History of Sunningdale Bowling Club

Brian King (with assistance from Peter O’Kill): History of Sunningdale Allotments

Berkshire Family History Society: Sunningdale

Virginia Water Community Website: Sunningdale Local History 1840

Sunningdale School History

Graham O’Connell: Notes on the History of Sunningdale Park

History of Sunningdale Golf Club

Englefield Green: Sunningdale Local History

Coworth House

Charters House

Tittenhurst Park

Fort Belvedere

Sunningdale War memorial (warmemorialsonline.org.uk)

Brief History of the Wentworth estate

Windsor Workhouse

Railway Passenger Stations in Great Britain: a Chronology – The Railway & Canal Historical Society (rchs.org.uk)

Public Houses, Inns and Taverns in Sunningdale

History of Comboni in England

Potted History of Sunninghill & Ascot

Other Sources

Weightman, C., Cheapside in the Forest of Windsor, Cheapside Publications, Cheapside, 2000

Hughes, G.M., The Forest of Windsor, Sunninghill, Windsor and the Great Park, Ballantyne, Hanson & Co, 1890 (now available as part of the British Library General Historical Collections)

Nash Ford, D., East Berkshire Town and Village Histories, NashFord Publishing, 1996-2017

Weightman, C., Remembering Wartime: Ascot, Sunningdale and Sunninghill (1939-1945), Cheapside Publications, Cheapside, 2006

Sumbler, M.G., British Geological Survey: London and the Thames Valley (4th edition), HMSO Publication

Sharpe, J., DIck Turpin: The Myth of the English Highwayman, Profile Books, 2004 (includes general information, i.e. not solely limited to Turpin).

Acknowledgements

I regard Peter O’Kill as Sunningdale’s Amateur Local Historian. He has written several short pieces on demand about the history of the village, e.g. for the Parish Council’s Official Guide back in 2014; penned detailed histories of the Village Hall and SADGA (the Gardening Club); heavily contributed to the Bowling Club’s history; as well as assisting me with my history of the allotments. I am extremely grateful that Peter and his wife Jane have allowed me access to his research notes, while Jane has also provided me with significant information on the Village Hall.

I thank Graham O’Connell who provided me with his notes on Sunningdale Park some years ago. I thank him for their use here, as well as in my Potted History of Sunninghill & Ascot. His notes, which are hosted on this site, can also be located via a link on the Parish Council’s website.

I thank the following individuals who have answered specific questions that I have asked them, or who have otherwise helped me: Joan Brightwell, Christine Gadd, Barbra Scoins-Arden, Nikki Tomlinson from the Parish Council and Diana Vernon-Smith, plus others who preferred to remain anonymous.

With respect to images, I thank: Jane O’Kill for providing me with copies of Sunningdale’s Millennium Calendar; John End and Peter O’Kill for the “Then and Now” pictures; John End for the picture of the Village Hall; and Andrea Ruddick for the picture of the unveiling of the war memorial. The Sunningdale Conservation Area map is taken from RBWM’s website, while the Parish map was supplied by Sunningdale Parish Council. Please contact me if you consider that I have infringed any copyright.

The following individuals have kindly read and commented on my early drafts. I thank Joan Brightwell, Stuart Henry, Peter Jackson, Janet King, Jane O’Kill, Peter O’Kill, Simon Roberts, Andrea Ruddick, Peter Stanaway and Diana Vernon-Smith.

All errors are mine.

Version History

Version 0.1 – 9th April, 2024 – very drafty

Version 0.2 – 13th April, 2024 – slightly less drafty. Added retirement villages and celebrities

Version 0.3 – 21st April, 2024 – added material on Charters and Broomfield Hall; added section on libraries; plus various minor changes

Version 0.4 – 30th April, 2024 – added info on Sacred Heart, picture of war memorial and minor changes along with first polishing

Version 0.5 – 7th May, 2024 – added material on the Village Hall and the CMI building. Show both the council’s Parish map and the Google version. Additions to the Bibliography section. Various minor changes and corrections, along with another attempt at polishing

Version 1.0 – 9th May, 2024

Version 1.1 – 21st May, 2024 – map changes and corrections to slideshow bugs in WordPress software

Version 1.2 – 28th June, 2024 – added section on carnival, festivals and fetes plus mention of Fort Belvedere and several minor changes

Version 1.3 – 11th February, 2025 – mention Wardour Lodge.