Contents

- Introduction

- Sparta

- Athenian Democracy

- The Roman Republic

- Witans and Things

- Beginnings of Parliament

- Rotten Boroughs

- Peterloo

- The Great Reform Act (1832)

- The Chartists

- Reform Act of 1867

- Reform Act of 1884

- Early Male Support for Female Suffrage

- Initial Limited Voting for Some Women in the 19th Century

- Women’s Suffrage Societies

- World War I

- The Representation of the People Act 1918

- The Representation of the People Act 1928

- Other Representation of the People Acts

- Who Has Voted?

- Bibliography and Further Reading

- Acknowledgements

- Version History

Let us start with some definitions:

- suffrage (or franchise) is the right to vote, typically used with respect to political elections

- active suffrage is sometimes referred to as the right to vote, as opposed to passive suffrage which is the right to stand for election

- universal suffrage is the right of all adult citizens to vote

- disenfranchisement is the process of excluding groups of people from the right to vote or to stand for election, based on: wealth or social status, gender, religion (e.g. Catholics in Ireland in the 18th century), age, nationality, criminality (prisoners typically cannot vote), et cetera

- types of democracy include: direct, e.g. referendums; representative (the most typical); and religious

- an oligarchy is rule by a small group of individuals. The right to vote within such regimes varies from non-existent, through limited to relatively complete, when they might be called “hybrid democracies”

- a magistrate in ancient times was akin to the likes of a CEO or similar senior administrator today. Our general understanding of the term today in the UK relates to the justice system, and dates back to 1285 when “good and lawful men were commissioned to keep the King’s Peace”.

Introduction

This potted history begins in ancient Greece with Sparta, which was considered to be an oligarchy, followed by Athens with its implementation of direct democracy, before moving on to the Roman Republic and its rather complex use of representative democracy. After the fall of the Western Roman Empire, it concentrates on events in Britain.

Voting, such as it was, was typically limited to free men, that is individuals with property, until the 19th century when a series of Reform Acts, enacted over a period of one hundred years, eventually led to universal suffrage in Britain. In the UK, women had been excluded from voting until the early 20th century.

Sparta

Along with several other Greek city-states, Sparta is considered to be an oligarchy. It consisted of two hereditary kings, the Gerousia (a council of elders), the Ephors (a board of five magistrates with an extensive range of judicial, legislative, religious and military powers) plus the Ecclesia (citizen assembly). The citizens were only allowed to vote on a limited set of proposals, which they were not permitted to debate.

Although they were not allowed to vote, Spartan women of citizen class had many privileges that other regimes did not offer. For example, they could inherit property, own land, and carry out business transactions.

Athenian Democracy

It is generally considered by historians that democracy started in Athens in the 6th century BCE. Rule by aristocrats had led to unrest which was eventually addressed by Solon, a statesman and lawmaker. His system of government was principally composed of:

- the Ecclesia, the citizen assembly (on certain occasions with a quorum of 6k). Free men over the age of 20 were eligible, but slaves, remotes (immigrants) and women were excluded. They debated and voted on proposals. This is an example of direct democracy

- the Boule (400 or 500) were administrators, for want of a better word, who guided the work of the assembly. They were voted into office by the assembly and had to be at least 30 years old. More senior posts, such as the archons (magistrates), were reserved for the wealthier classes

- the courts. There were no judges and the minimum jury size was 200, with a maximum of 6,000.

The advantages that were bestowed on the wealthier individuals in Solon’s system inevitably led to some discontent, which Cleisthenes and Pericles subsequently attempted to address.

Athenian democracy was suppressed in 322 BCE after the Macedonians had become the powerhouse in Greece.

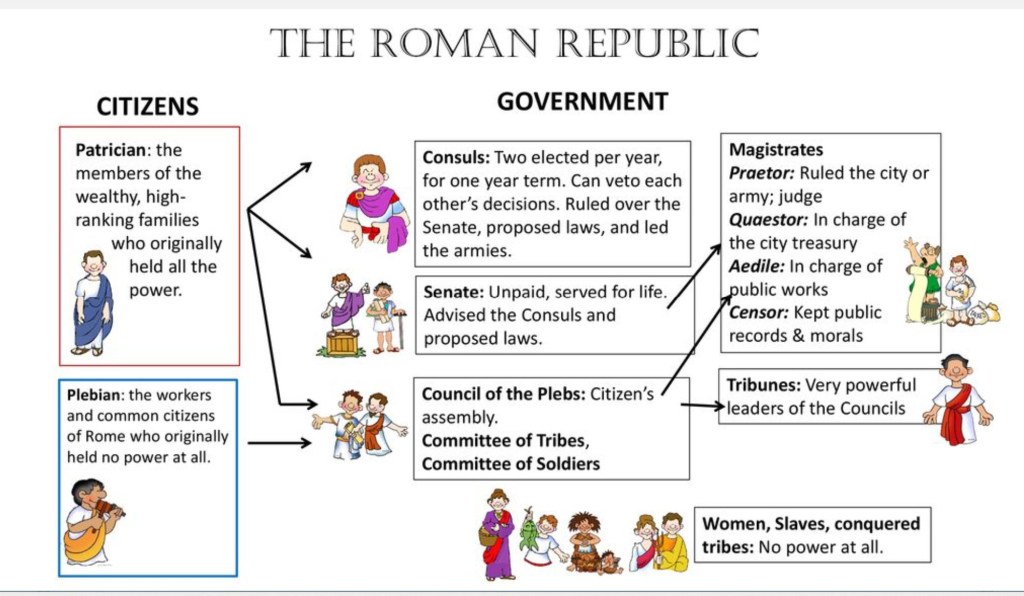

The Roman Republic

The Roman Republic (509 BCE – 27 BCE) was initially ruled by the patricians, wealthy aristocrats, who made up the Senate. Although there were annual elections, it was an oligarchy with the most powerful families dominating the magistracies. As in the Greek city-states, this led to discontent among the plebeians (the rest of the Roman citizens).

The Senate was forced to relent, allowing the plebeians to elect their own representatives, annually. These were the tribunes, and there were eventually 10 of them, who provided checks on the power of the Senate and the magistracies. They were assisted by the aediles who were elected with responsibility for the maintenance of public buildings and festivals.

Separately, there were assemblies in the Roman Republic where citizens voted on laws, elected officials, and made decisions on various political and legal matters. There were three main types:

- the Centuriate who voted on military matters and elected consuls, praetors and censors. A consul was the highest elected official in the Republic. There were two consuls each year

- the Tribal, organised by geographical divisions, who elected lower-ranking magistrates such as aediles and quaestors (treasury officials)

- Plebeian, who voted for the tribunes, as mentioned.

Women, slaves, and initially those living outside Rome, were not entitled to vote, while Centuriate and Tribal voting rights favoured the elite.

The end of the Republic and the arrival of the Roman Empire with the emperor Augustus saw a shift to imperial power, along with reduced influence in the Senate, while other elements of the political system, certainly at the higher levels, became more ceremonial.

Witans and Things

The end of the Western Roman Empire in the 5th century CE typically led to a system where a ruler had a council of advisors. Started in Germanic societies, the Witan, as it was known, was made up of ealdormen (earls), thegns (noblemen below earls) and bishops. It is confirmed that such a system operated in the petty kingdoms of Anglo-Saxon England from the 7th century CE.

After the Norman Conquest, the Witan became known as the Curia Regis. In the early Norman period, there was a permanent inner circle, which came to be known as the Privy Council, and the Great Council which only met occasionally. The latter was used by William the Conqueror at the Christmas Council in 1085 to commission the Domesday Survey.

At a lower level, governing assemblies for regions or areas, consisted of free men within the community. They were known as Things or Folkmoots. Meetings were typically held several times each year at venues that were easy to reach. Thing (or its equivalent) in present day place names can indicate where these meetings were held, certainly where Vikings had settled. Examples include Thingwall on the Wirral, Dingwall in the Highlands, and Tynwald, the name given to the Isle of Man’s parliament. Participants were limited to free men, individuals with property, but it is unclear if there was any system of seniority which limited who was able to speak at such meetings.

Beginnings of Parliament

Reductions in the king’s power began to surface towards the end of King John’s reign (1199-1216). Contributory factors that led to unrest among the barons around this time included: funding for the Third Crusade; payment of the ransom for Richard the Lionheart after he had been held by Leopold of Austria on his return from the Crusade; followed by John’s general unpopularity which was based on his own heavy financial demands, his partial justice and his abuse of feudal incidents, reliefs and aids.

This all led to Magna Carta (1215), which contained three principal elements: the king was to be subject to the law; the king could only make law and raise taxation with the consent of the community of the realm; and the obedience owed by subjects to the king was conditional and not absolute.

The term “Parliament” to describe the Great Council was first used in 1236. It comes from the French parler which means to talk and discuss. French, introduced by the Normans, was regarded as the official language of England until the 14th century.

Henry III (1216-1272) subsequently tried, as far as possible, to sideline the barons by ignoring their advice and limiting their input to consent to levy taxation. Almost inevitably, the barons tried to increase their sphere of influence with the Provisions of Oxford (1258) which included the establishment of a 15-man council of barons to advise the king on matters of government. This led to the baronial wars when those who were loyal to Henry were defeated by Simon de Montfort’s forces.

There were subsequently two Parliaments that were organised by de Montfort’s group. His second Parliament was called on 14th December 1264. Summoned were: 23 lay magnates, 120 bishops, two knights from each county and two citizens from each town, along with four men from each of the Cinque Ports. However, De Montfort’s death at the battle of Evesham in 1265 allowed Henry to undo these reforms.

Edward I (1272-1307) was more pragmatic than his father, realising the value of keeping Parliament onside. It typically met twice a year, at Easter and at Michaelmas. The Parliament of 1295, subsequently to be known as the Model Parliament, summoned 49 lords and 292 representatives of the Commons, including two knights from each county, two burgesses from each borough and two citizens from each city. A burgess was a free male citizen, typically an important figure in the local community.

In 1341, Parliament separated for the first time, creating an Upper Chamber for the nobility and clergy and a Lower Chamber for the rest. This Upper Chamber became known as the House of Lords from 1544, and the Lower Chamber as the House of Commons. They were known collectively as the Houses of Parliament.

There were no specific rules concerning the right to vote in the counties, leading to the view that only the better-off should be allowed to vote. From 1430 onwards, the franchise for the election of knights of the shire in the county constituencies was limited to forty-shilling freeholders, meaning men who owned freehold property worth forty shillings (two pounds) or more. So, only relatively prosperous individuals were eligible.

Boroughs also had no specific rules with regard to voting, but they were allowed to continue with whatever local rules they had previously adopted, typically limiting eligibility to prosperous men.

This system of franchise effectively remained unchanged for 400 years.

From the 1540s, the presiding officer in the House of Commons became formally known as the Speaker, having previously been referred to as the prolocutor or parlour (a semi-official position, often nominated by the monarch, a position that had existed ever since Peter de Montfort had acted as the presiding officer of the Oxford Parliament of 1258). This was not an enviable job. When the House of Commons was unhappy, it was the Speaker who had to deliver this news to the monarch. This began the tradition whereby the Speaker of the House of Commons is dragged to the Speaker’s Chair by other members, once elected.

It was during the sitting of the first Rump Parliament in 1648 that members of the House of Commons became known as MPs. While numbers varied, there were around 500 MPs after the Restoration of the Monarchy in the late 1600s; 560 after the Union with Scotland in 1707; and 650 after the Union with Ireland at the beginning of the 19th century.

Rotten Boroughs

Also called nomination or proprietorial boroughs, they had become sources of significant unrest by the 19th century. Old Sarum is regularly mentioned in this regard. It had been a busy cathedral city until Salisbury Cathedral was built two miles away to replace the existing edifice. This naturally attracted merchants and workers to New Sarum, as it was called, and Old Sarum was effectively abandoned, although it retained its right to elect two MPs, effectively putting them under the control of the local landowning family. William Pitt the Elder was one of their MPs (1735-1747).

Peterloo

There was an economic slump after the Napoleonic Wars. Factors included high unemployment, not helped by soldiers returning after the Napoleonic Wars, and the effect of the Corn Laws. Radicals, seeking change, decided that parliamentary reform was a prerequisite.

Manchester had been a medium-sized town in the early 1700s with a population of around 10,000, not dissimilar to the likes of Birmingham, Bristol, Liverpool and Glasgow at the time. However, the Industrial Revolution resulted in massive increases in their respective populations. Manchester’s was around 100 thousand in 1819, but under the continuing centuries-old voting system it had no representation in Parliament.

It is estimated that no more than 11% of the male population of Britain had the vote. In 1817, a petition for parliamentary reform, signed by 0.75 million, had been rejected by Parliament.

A rally was organised at St. Peter’s Field, Manchester in August 1819. Fearing unrest, the local magistrates ordered the local Yeomanry to arrest Henry Hunt, the main speaker, along with several others on the platform. They killed one child in the process, and then the 15th Hussars were ordered to disperse the crowd. Estimates vary but it is thought that 17 people were killed and up to 700 injured.

The Manchester Observer, one of the newspapers that were present, called it the Peterloo Massacre, the battle of Waterloo having only taken place four years previously. With the French Revolution and the American War of Independence still in its collective memory, the authorities were convinced that rebellion was a strong possibility, helped no doubt by the discovery of the Cato Street Conspiracy in the following year. Hunt was jailed for 30 months and Wroe, the editor of the Manchester Observer, for 12 months. The Six Acts was quickly passed, aimed at suppressing meetings and gagging radical newspapers. By the end of 1820, all the significant radical reformers were in jail, and the Manchester Observer had been forced to close in 1821, the same year that the Manchester Guardian was founded.

The Great Reform Act (1832)

Pressures for reform had continued both outside and inside Parliament during the 1820s, another factor being the rise of the middle class and their desire for representation. This eventually led to the first Reform Bill, which was effectively blocked by the Tories in the Commons. The second attempt was also rejected, this time by the Tory peers in the Lords with the help of the Lords Spiritual, leading to public violence in various parts of the country.

The “Days of May” in 1832 was a period of significant political agitation which brought fears of revolution. The Duke of Wellington circulated a letter among Tory peers, encouraging them to desist from further opposition, and warning them of the consequences of continuing. At this, enough opposing peers relented, typically by abstaining, leading to the passing of the Great Reform Act of 1832.

In brief, 143 borough seats, mostly of the rotten borough variety, were abolished, and industrial cities like Manchester were now represented. Extensions to the franchise, in part by including some renters in boroughs and leaseholders in counties, led to the number of men who were entitled to vote rising from 400 to 650 thousand, although this still only represented 7% of the population. In essence, it might be said that middle class men were the principal beneficiaries.

The Chartists

Unhappy with the limited scope of the Great Reform Act of 1832, six MPs and six working men, including William Lovett from the London Working Men’s Association which had been set up in 1836, formed a committee which published the People’s Charter in 1838. This set out the movement’s main aims which would give working men a say in lawmaking: they would be able to vote; their vote would be protected by a secret ballot; and they would be able to stand for election to the House of Commons because property qualifications would be removed and MPs would be paid.

Its 1839 petition was signed by 1.3 million, and a second one in 1842 by over 3 million, but both were rejected by Parliament. 1842 saw strikes and other instances of unrest for which the Chartists seemed to be blamed, although they were other factors at play such as the general hostility towards the Corn Laws.

In the wake of the French Revolution of 1848 when the king, Louis Phillipe, was forced to abdicate and the Second Republic was proclaimed, a meeting was planned to take place on Kennington Common, after which a march would deliver another petition to the Government. However, the Government invoked an old law which stated that no more than 10 people could deliver a petition, and it recruited 100 thousand special constables to deal with any trouble, even though it was planned to be a peaceful meeting. It was indeed a peaceful meeting, but no march took place, although the petition was delivered and rejected yet again. Chartism markedly declined after this, its final Convention in 1858 attracting very few delegates.

Reform Act of 1867

Pressures from the Reform League, which was established in 1865, and a rally attended by 200 thousand in Hyde Park in 1866, which the authorities tried unsuccessfully to stop, were factors for further change. Outside factors which also had to be taken into account by the authorities were the Union victory in the American Civil War and continuing unrest in Europe, led by the likes of Marx, the Anarchists and others.

The 1867 Act:

- granted the vote to all male householders in the boroughs, as well as lodgers who paid rent of £10 a year or more

- reduced the property threshold in the counties and gave the vote to agricultural landowners and tenants with very small amounts of land.

The effect was that it doubled the number of adult males who could vote from 1 million to 2 million, approximately 30% of the adult male total. In addition, there were various borough changes.

Reform Act of 1884

Gladstone’s government extended the borough rules on property qualifications to the counties, resulting in 5.7 million men now being able to vote. However, this still left 40% of males who did not have the vote, nor did any women of course.

The Redistribution of Seats Act 1885 introduced the concept of equally populated constituencies, mandating the abolition of constituencies with populations below a certain threshold level.

Early Male Support for Female Suffrage

Early supporters included:

- Jeremy Bentham, the philosopher and social reformer of the late 18th and early 19th century, who advocated equal rights for women

- Henry Hunt, the main speaker at Peterloo who later became an MP

- John Stuart Mill, the son of James Mill, Bentham’s secretary, was a philosopher and later MP who published the essay, entitled The Subjection of Women in the 1860s.

The subject of female suffrage was also discussed on various occasions in the Commons through private members’ bills. However, although the majority voted in favour, they all lacked government support and were crowded out of the legislative agenda.

Initial Limited Voting for Some Women in the 19th Century

- The Vestries Act 1818 allowed single women ratepayers to vote in parish vestry elections, but this provision was promptly removed in the 1832 Reform Act

- Municipal Franchise Act 1869 allowed single women ratepayers to vote in local elections

- The Local Government Act 1894 allowed women with property to become councillors, act as Poor Law Guardians, as well as vote in municipal elections.

Women’s Suffrage Societies

The denial of voting rights for women, despite their contributions to society and their similar circumstances to men, cultivated a growing sense of injustice which led to the establishment of a string of regional organisations that strove for female suffrage, starting with the Sheffield Female Political Association (1851) which submitted a petition to the House of Lords.

Lydia Barker, secretary for the Manchester Society for Women’s Suffrage, was responsible for founding the National Society for Women’s Suffrage (NSWS) in 1867, an amalgamation of local groups.

After her death, the National Union of Women’s Suffrage Societies (NUWSS) was eventually founded by Millicent Fawcett in 1897. Local societies were affiliated to the NUWSS, although they retained a significant amount of autonomy. There were 16 affiliates in 1903. They were collectively known as suffragists. In general, they used petitions and lobbying to further their cause.

Also in 1903, Emmeline Pankhurst founded the Women’s Social and Political Union (WSPU), an all-women suffrage advocacy organisation dedicated to “deeds, not words”. She had previously established the Women’s Franchise League in 1889 with her husband and others, but she ultimately decided that direct action was necessary to achieve their aims. This was in sharp contrast to the suffragists who were strictly non-militant.

Known as the suffragettes, a term initially used by a journalist, its initial actions included heckling, smashing windows and assaulting police officers, and later chaining themselves to railings. However, it stepped up its actions in 1912 when it began an arson and bombing campaign, which resulted in four dead and 24 injured. Lloyd George’s house was among the properties that were targets. Prison sentences for serious offences led to hunger strikes, and on to what was known as “the Cat and Mouse Act”, when weakened suffragette prisoners were released, but returned to prison when their health improved, only for hunger striking to start again .. ad infinitum.

Arguably the most famous suffragette incident, not least because it was recorded on camera, was that of Emily Wilding Davison, attempting to put the colours of the WSPU on the king’s horse during the running of the 1913 Epsom Derby, and being killed in the process.

World War I

The suffragettes stopped their direct action campaign when war was declared, and concentrated its efforts on helping the government to recruit women for war work. The suffragists also suspended their front-line activities and helped the war effort by putting their main efforts into voluntary work. This is not to say that their campaigning stopped altogether.

Prime Minister Asquith had by this time made it known that he considered female franchise to be inevitable, albeit within the framework of general reform in this area.

The Representation of the People Act 1918

Seen by many as part reward for the work of women during the conflict, notably work in munitions factories and other roles that needed to be filled while men were away fighting, and part reward for men’s sacrifices during the conflict, this act was the first significant move towards universal suffrage.

With respect to men, property qualifications no longer applied, and those who were 21 or over were entitled to vote. Women who were 30 and over, and met certain minimal property qualifications were also entitled to vote. Interestingly, women who were 21 or over were able to stand for election (passive suffrage).

The first woman to be elected to Parliament was Countess Constance Markiewicz who, being a member of Sinn Fein, did not take up her seat. The first person to do that was Nancy Astor in 1919.

The net effect of the 1918 Act was to add 8.4 million women and 6.3 million men to the electorate.

The Representation of the People Act 1928

By the time of this Act, twelve women had been elected to Parliament. This is also called the Equal Franchise Act, or sometimes the Fifth Reform Act. It gave the vote to all women aged 21 or over, as well as men.

Other Representation of the People Acts

The Acts of 1948 and 1969 are particularly notable. Plural voting was abolished in 1948. This had previously allowed individuals with property in multiple constituencies to vote in each one. Another rule had allowed members of a university to vote in that constituency, as well as in their home constituency. These university constituencies were abolished.

Finally, the 1969 Act lowered the voting age to 18 for men and women.

Who Has Voted?

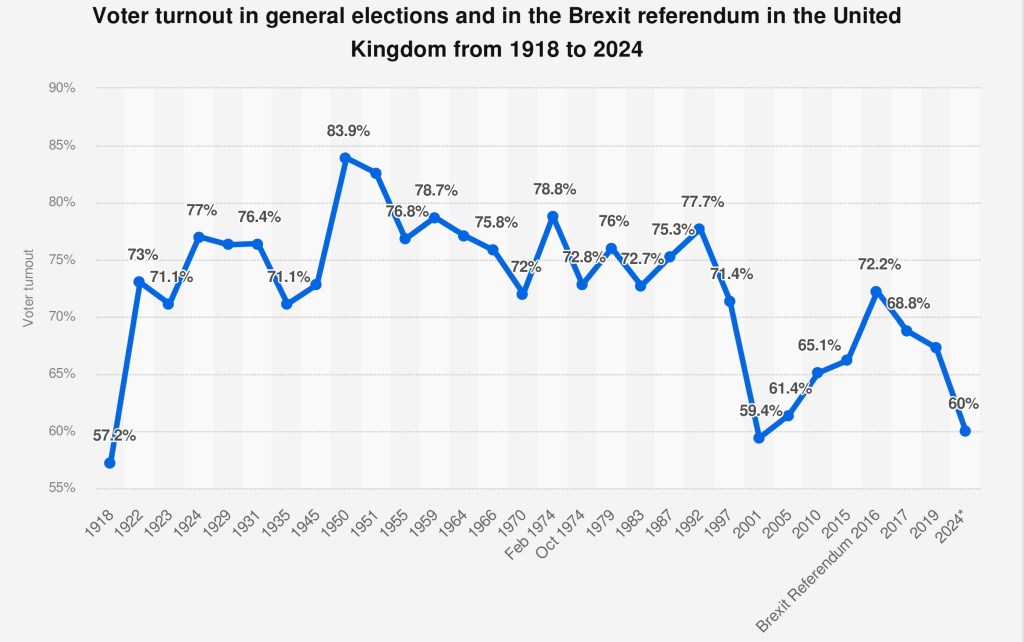

This graph shows the percentage of the electorate that has voted at UK general elections between 1918 and 2024.

The chart includes the Brexit referendum in 2016. There have been two other national referendums in the UK: the issue of continuing membership of the European Community (EC) in 1975; and the question on the possible introduction of the alternative voting system in 2011.

Bibliography and Further Reading

Because links frequently change or disappear, Wikipedia and Encyclopaedia Brittanica are generally preferred sources in this section.

Suffrage – Wikipedia

Types of democracy – Wikipedia

Athenian democracy – Wikipedia

Roman Republic – Wikipedia

Roman assemblies – Wikipedia

Quaestor – Wikipedia

Consul – Wikipedia

Rome’s Transition from Republic to Empire

Centuriate assembly – Wikipedia

Germanic kingship – Wikipedia

Thing (assembly) – Wikipedia

Witan – Wikipedia

Witenagemot – Simple English Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Curia regis – Wikipedia

Overview – UK Parliament

Parliament-the-Institution.pdf

Parliament of England – Wikipedia

Model Parliament – Wikipedia

Simon de Montfort, 6th Earl of Leicester – Wikipedia

Knight of the shire – Wikipedia

Research Paper on the history of the Parliamentary Franchise

Number of Westminster MPs – Wikipedia

Rotten and pocket boroughs – Wikipedia

Old Sarum – Wikipedia

Suffrage United Kingdom – Wikipedia

Peterloo Massacre – Wikipedia

Reform Act 1832 – Wikipedia

Reform Acts – Wikipedia

London Working Men’s Association – Wikipedia

Chartism – Wikipedia

Birth of a Movement | Historic England

Representation of the People (Equal Franchise) Act 1928 – Wikipedia

The Subjection of Women – Wikipedia

National Society for Women’s Suffrage – Wikipedia

National Union of Women’s Suffrage Societies – Wikipedia

Women’s suffrage in the United Kingdom – Wikipedia

Women’s Social and Political Union – Wikipedia

Millicent Fawcett – Wikipedia

Emmeline Pankhurst – Wikipedia

Christabel Pankhurst – Wikipedia

Millicent Fawcett – Wikipedia

Start of the suffragette movement – UK Parliament

Acknowledgements

All images have been found on the Internet. The captions are links to the creators. Please contact me if you consider that I have infringed any copyright.

All errors in this document are mine.

Version History

Version 0.1 – April 4th, 2025 – very drafty

Version 0.2 – April 6th, 2025 – still drafty

Version 0.3 – April 20th, 2025 – comments from JEK

Version 1.0 – May 7th, 2025