As with all my potted histories, this one is aimed solely at the general reader. The simple objective is to provide a modest piece which is both informative and readable.

It covers the history of languages and writing systems, the former primarily European languages before focusing on the English language, while the latter starts with the Sumerians and Ancient Egyptians in the Middle East before moving westwards across Europe.

With respect to dates, note that BCE and CE are used in preference to BC and AD in my histories.

Fill in and submit the form on the Contact Me page if you have any questions or feedback.

Contents

- In The Beginning

- Writing Systems

- Before Cuneiform

- The Sumerians and Cuneiform

- Ancient Egypt

- The First Alphabets

- The Latin Alphabet

- Slavs

- Languages

- Proto-Indo-European Language Branches

- Italic Branch

- Celtic Branch

- Germanic Branch

- Old English

- Arrival of the Normans

- Spoken Languages in England

- Middle English (1150-1470)

- Early Modern English (up to 1700)

- Modern English (1700 – the present day)

- Odds and Sods

- The Rosetta Stone

- Writing Tools

- Sources of English Vocabulary

- Ogham Script

- Bibliography and Further Reading

- Acknowledgements

- Version History

In The Beginning

Speech arrived with developments in the brain and vocal tracts of Homo Sapiens. Estimates vary as to when this might have happened, with the majority of views lying in the period between 100k and 200k years ago. One opinion has it that it must have been present at least 135k years ago to explain cultural and social patterns.

Cave paintings can be considered as part art (for art’s sake) and part communication. The earliest example has so far been located in Indonesia, dated at 67.8k years ago, while numerous examples that can be found in France and Spain are circa. 30-40k years old.

Tally sticks, notches made initially on bone, some dating to circa. 40k years ago, were the earliest forms of counting and may also be regarded as a form of communication.

After Homo Sapiens migrated out of Africa, language gradually formed into a number of major families:

- Indo-European (English, Hindi, French, Spanish, Russian, Persian)

- Sino-Tibetan (Chinese languages, Burmese)

- Afro-Asiatic (Arabic, Hebrew, Amharic)

- Niger-Congo (Swahili, Yoruba, Zulu)

- Austronesian (Malay, Tagalog, Hawaiian).

This potted history is solely concerned with the Indo-European family, eventually focusing exclusively on the English language.

A proto-language is a reconstructed ancestor language from which a group of modern, related languages are believed to have evolved. Proto Indo-European (PIE) is thought to date back to the 3rd or 4th millennium BCE. There is much debate as to where it might possibly have been spoken initially, with the academic consensus seeming to place it around Ukraine / Southern Russia.

However, as we ideally need written evidence on the history of language, it is preferable that we consider the history of writing systems in the first instance before tackling languages.

Writing Systems

Writing began in the Sumerian and Egyptian civilisations as pictorial drawings which represented concrete objects; then becoming more stylised and abstract; seeing the addition of symbols which represented sounds rather than just ideas; before the appearance of alphabets that totally represented sounds.

Before Cuneiform

The earliest significant development of farming began in the Fertile Crescent (Middle East) circa. 12k years ago. Surplus crops quickly led to the establishment of trading networks, initially along the Tigris and Euphrates rivers. Trade necessitated forms of accounting and record-keeping, and so clay tokens emerged in Mesopotamia around 8000 BCE. They sat inside bullae (clay envelopes) and were used to represent quantity and commodity (e.g. grain), but not quality or category. By the early 4th millennium BCE, the content of the envelope could be displayed on the outside.

The Sumerians and Cuneiform

The Sumerian civilisation emerged in southern Mesopotamia in the early 4th millennium BCE. It is best known for the establishment of city-states such as Uruk and Ur, and inventions such as the wheel, irrigation techniques and the cuneiform script.

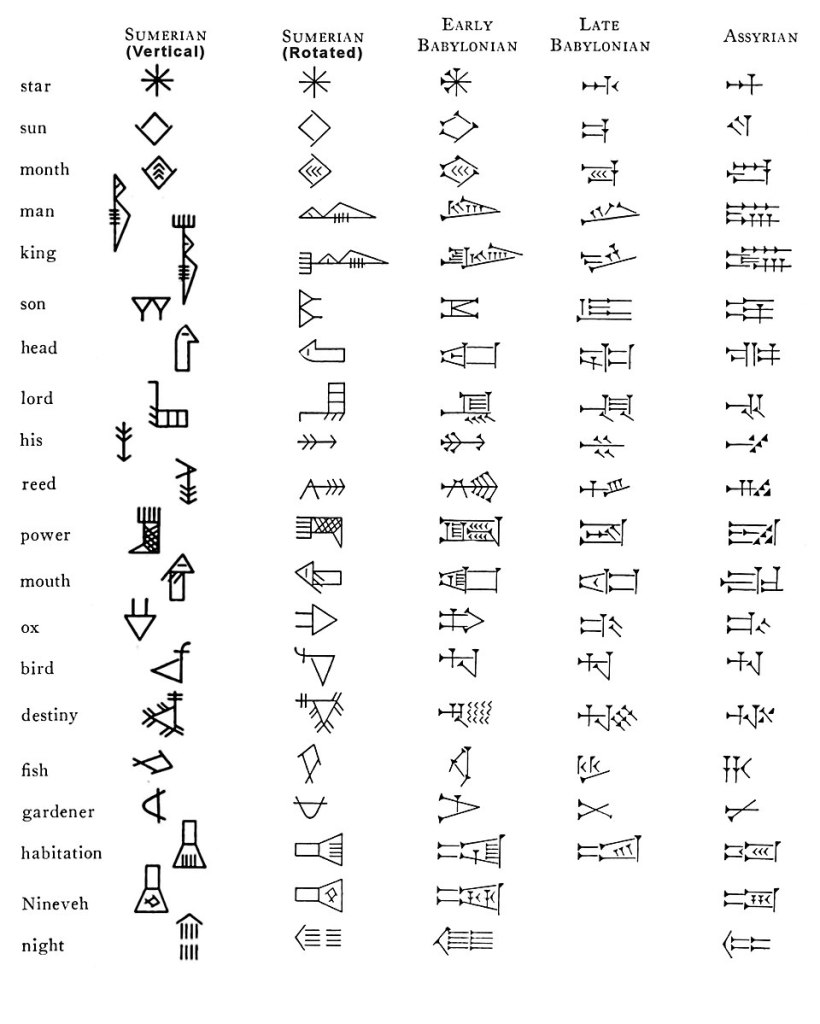

Continuing with the trading theme, the earliest cuneiform signs were pictograms (pictures which represented commodities) that were drawn on clay by the Sumerians circa. 3400 BCE. However, drawing was too slow and a reed stylus was adapted to make impressions on clay tablets, representing numbers and pictograms. Pictograms could be joined together: mouth plus bread = eat; mouth plus water = drink. They quickly started to become more abstract. A logogram looked less like an object, although its relationship with the object was clear.

Sumerian cuneiform script had matured by around 2400 BCE, encompassing pictures, symbols and determinate marks, the latter being used to classify and clarify the meaning of a word or phrase, e.g. religion, place et cetera. It effectively employed the Rebus principle, which uses pictures and symbols for their sounds, not their meanings, to represent words or phrases.

Scripts were initially written vertically, top to bottom in columns which ran from right to left. However, somewhere around 2000 BCE the direction was switched, being written horizontally, left to right (similar to modern English).

It is estimated that there were 400-600 elements in the cuneiform script by this stage although there had previously been more than twice that number. It makes one think that there must have been few individuals, other than scribes, who could understand them all.

The Akkadians and Babylonians, who followed on from the Sumerians in Mesopotamia, used and improved cuneiform, gradually employing it for literature (e.g. The Epic of Gilgamesh c. 2100 BCE), laws (Code of Hammurabi 1755-1751 BCE), science and religion.

Cuneiform continued in existence until c. 100 CE.

Ancient Egypt

There is some debate about which came first, cuneiform or Egyptian hieroglyphs. On balance, the Sumerians appear to get the academic vote, but there isn’t much in it.

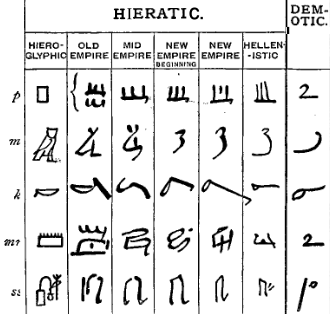

Hieroglyphs, stylised pictures of objects or words date to circa. 3200-3000 BCE. They appeared principally on stone monuments and religious works, and were written from top to bottom, either left to right or right to left, the direction of the faces in the pictures indicating which.

They were far too slow to be useful in the real world of business and administration, and so they were soon followed by the hieratic script. Derived from hieroglyphs, but much simplified, it contained logograms (more abstract than pictograms), phonetic signs and determinatives. Cursive and flowing, it was usually written from right to left with a reed brush, using black and red ink on papyrus, and it became the everyday script for two millennia.

The demotic script, which followed much later, was based on the hieratic script but was quicker to write, being used for document writing, e.g. religious, legal, literary, business et cetera. It was employed from c. 700 BCE to 400 CE.

The First Alphabets

C. 1800 BCE, Proto-Sinaitic Script was being used by Semitic speakers in the Sinai. In essence, it simplified Egyptian symbols into sounds, not ideas, thus developing the first alphabetic principles.

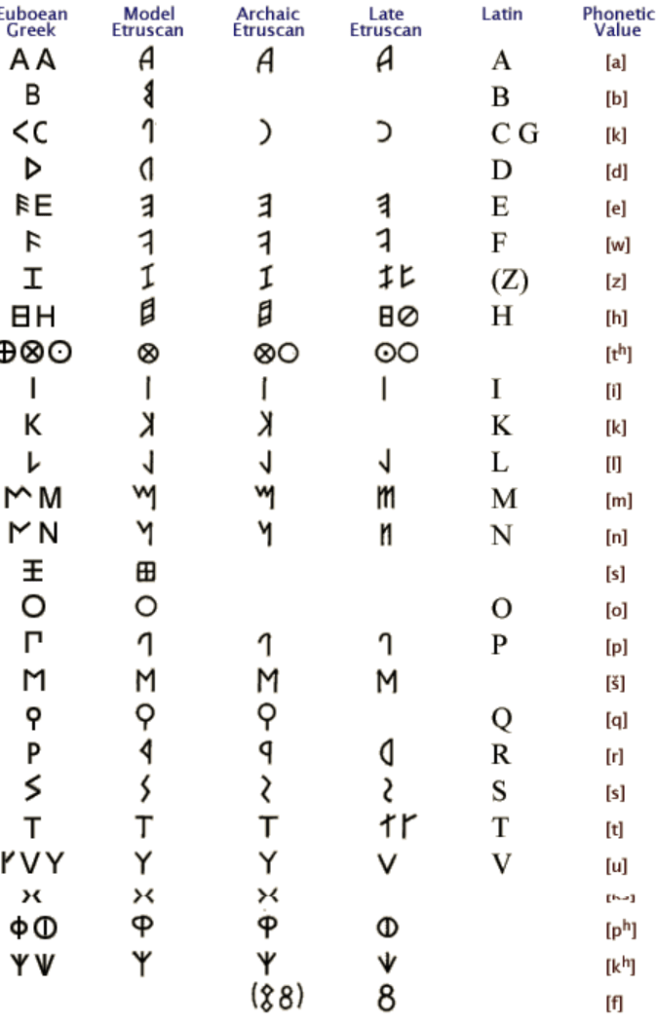

This was followed by the Phoenician Alphabet around 1200 BCE. The Phoenicians, based in the Levant (primarily modern-day Lebanon), were the major traders around the Mediterranean for the best part of a millenium. Their alphabet is known as an abjad, which means that there are only consonants, vowels are to be inferred.

During the second millennia BCE, the Greeks had been using Linear A and Linear B, scripts, neither of which had evolved from the Mesopotamians or Egyptians; the former had appeared during the Minoan civilisation and the latter during the Mycenaean civilisation. However, around 800 BCE they adopted the principles of the Phoenician Alphabet, adding vowels to it.

Greeks colonized Southern Italy around the 8th century BCE, establishing cities such as Naples. The Etruscans, who populated Tuscany and its environs, were influenced by these Greeks when forming their own alphabet.

The Latin Alphabet

Rome was founded in 753 BCE, becoming a republic in 509 BCE. It was profoundly influenced by the Etruscans, their previously established next-door neighbours. The first Latin alphabet emerged around the 6th century BCE. It contained 21 letters initially, all upper case (known as majuscule letters). G and Y were added during antiquity, while J, U and W were included later during the mediaeval period.

To improve speed, scribes developed cursive, more rounded forms of letters called uncials, which eventually came to form the basis of lower-case letters that slowly evolved, eventually resulting in the Carolingian miniscule in the 9th century CE. This is the ancestor of modern Roman typefaces, a category of serif fonts which includes Times New Roman, Garamond and Baskerville.

The success of the Romans in building their empire inevitably led to an ever-increasing use of their alphabet. After the decline of the Western Roman Empire in the 5th century CE, the increasing power of the Catholic Church ensured its continuation and further growth via its various roles in governments, administrations and education, as well as the use in its own liturgy. Meanwhile, in the Eastern Roman Empire which was based in Byzantium and survived until the 15 century CE, the Ancient Greek alphabet thrived.

Slavs

Slavic requirements produced the Cyrillic script in the 9th century CE, which was based on the Greek alphabet. Various alphabets came to be based on this script, including Serbian and Russian, as well as non-Slavic variants such as Kazakh and Mongolian.

Languages

Languages are living systems:

- constantly adapting to new needs, technologies, and cultures;

- driven by social interaction, migration and generational shifts, leading to new words, altered pronunciations evolving grammar to reflect the changing world and the identity of speakers, even if unconsciously.

This natural evolution can happen gradually or rapidly, making languages distinct from their ancestors over centuries.

Proto-Indo-European Language Branches

Proto-Indo-European (PIE) gradually split into a number of branches in Europe, principally Italic, Celtic and Germanic.

Italic Branch

Latin was the major language. It’s history follows these developmental stages: pre-literary Latin up to 240 BCE; Old Latin, 240 to 100 BCE; Classical Latin (the preserved literary Latin), 100 BC to 14 CE; Silver Age, 14 CE to around 120 CE; Archaic Latin, 120 CE to 200 BCE; Vulgar Latin of late antiquity, 200 CE to 600 CE; Middle Latin, 600 CE to the fourteenth century; and, subsequently, Modern Latin.

Other members of the Italic branch included Picene, Oscan and Umbrian, which all mostly died out.

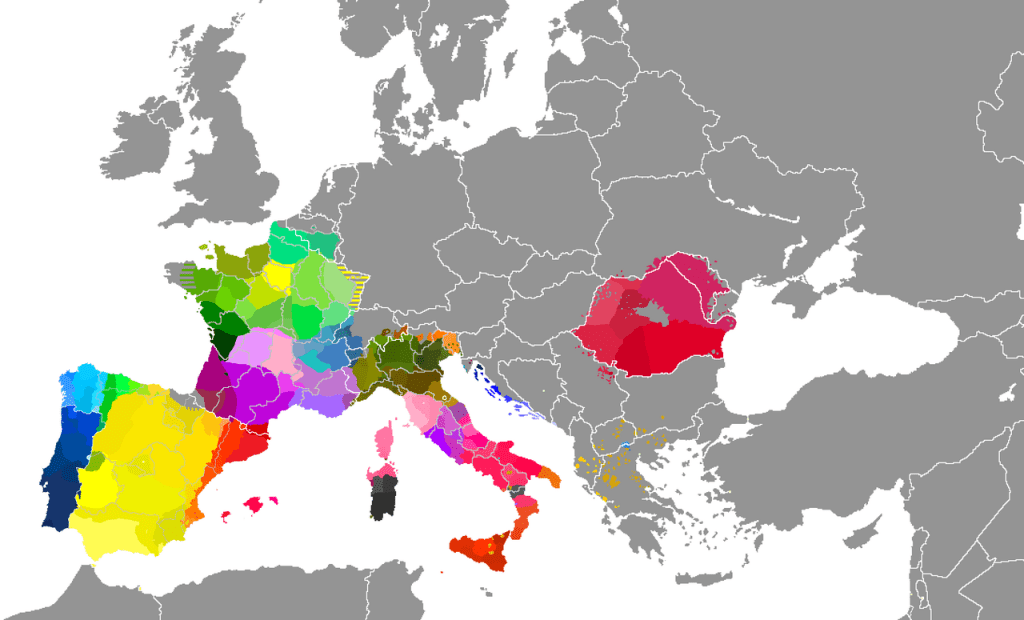

Spoken Vulgar Latin, as it is known, continued to evolve on top of local languages across the Roman Empire, eventually creating the Romance family of languages. Each daughter language was spoken in proto-forms for many centuries before finally being entrusted to parchment: French in the 9th century; Italian in the 10th century; Provençal of southern France a century later; the three Ibero-Romance languages Spanish, Portuguese and Catalan in the 12th century; and Romanian in the 16th century.

Click on the captions to see the original map, along with descriptions of the legends.

Celtic Branch

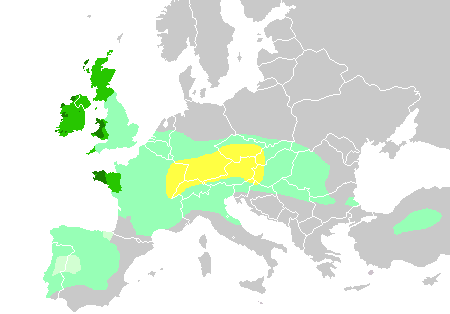

Diverse tribes across Europe came to share a common culture during the late Bronze Age and the Iron Age. It is thought that the main drivers, or influencers, were three closely related groups, starting with the Urnfield culture in the Upper Danube from around 1300 BCE, although little is known about it.

It was followed by the Hallstatt culture, the name of a site in Southern Austria, which existed from c. 1200 BCE to c. 450 BCE. The area was rich in resources such as salt, iron and copper, and trade along waterways was probably the primary means by which their culture spread. Although it extended to both the east and the west, it was principally to the west that the ancient Celtic culture would develop.

And finally, the third influencer was the La Tene culture, named after a site on the shores of Lake Neuchâtel, which dates from c. 450 BCE to c. 50 BCE. It also spread across much of Europe, from Ireland in the west to Romania in the east, once again initially via trade. Their culture is arguably best known for its art which included spirals and repeating geometrical patterns.

Language was a key component of the Ancient Celtic culture. It is thought that Proto-Celtic was spoken between 1300 and 800 BCE, after which it split into two groups, Continental Celtic and Insular Celtic. Continental Celtic included Gaulish (France), Celtiberian (Spain) and Lepontic (Alpine Region). This group had largely disappeared by 500 CE.

Insular Celtic was composed of two sub-groups, Brittonic and Goidelic. Brittonic was spoken across Britain from around 600 BCE to 600 CE, spanning the Iron Age and the period of Roman occupation. However, it was subsequently restricted to the west after the later arrival from the 5th century CE onwards of Germanic tribes such as the Angles, Saxons and Jutes in the east. Brittonic evolved into languages such as Welsh, Cornish and Breton, while the Goidelic branch comprised Scottish Gaelic, Irish Gaelic and Manx.

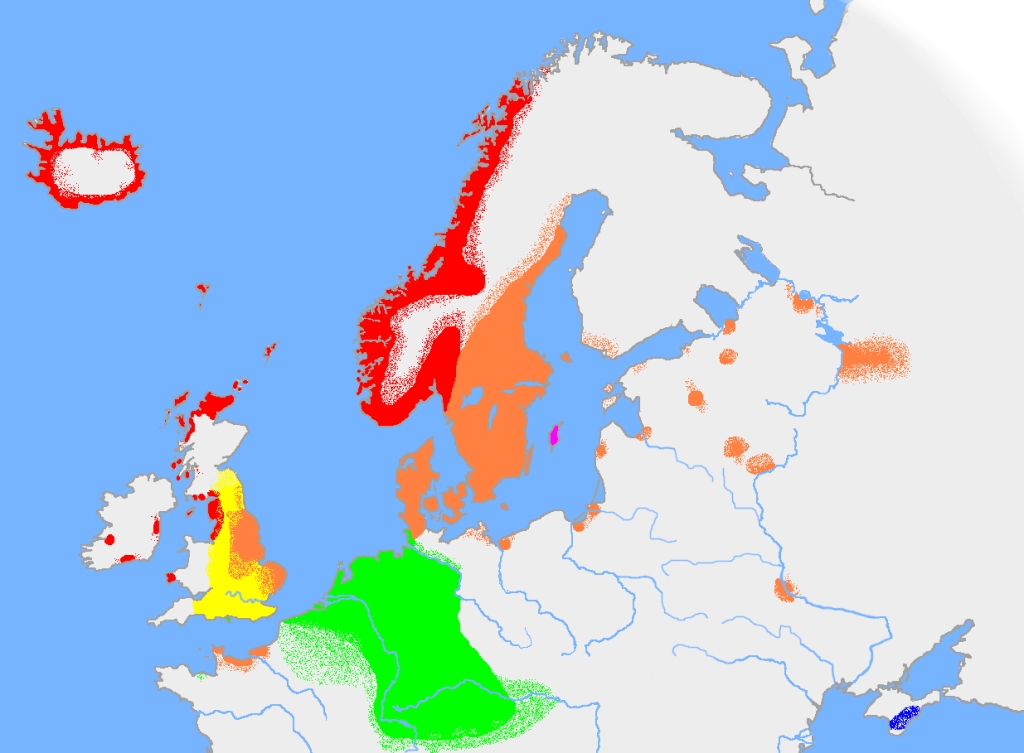

Germanic Branch

Proto-Germanic diverged into the eastern, western and northern Germanic groups. In the east, Gothic, the main language, was spoken by the Ostrogoths and Visigoths between the 4th and 7th centuries CE. The Western group produced German, English, Dutch and Frisian, while Old Norse was to be found in the north.

Old English

From the 5th century CE onwards, Old English initially developed from North Sea Germanic after the arrival of the Angles, Saxons and Jutes, along with some residual use of the Celtic Brittonic.

The Viking invasions and occupation (notably the Danelaw) from the 9th century CE inevitably had a significant influence on the language, bringing elements of Old Norse. Everyday words of Norse origin include egg, window and husband; pronouns such as they, them and their; verbs such as take, give and call; and place names that ended in by (Grimsby), thorpe (Cleethorpes) and kirk (Ormskirk) et cetera.

Arrival of the Normans

After the Norman Conquest, Anglo-Norman French, an amalgam of languages including Old Norman French, gradually appeared in England.

Latin replaced Old English in official documentation; the latter being gradually confined to copies of old texts. The low point for written English probably occurred between 1150 and 1200, after which Middle English began to appear in some literary texts, notably the poem The Owl and the Nightingale in the early 13th century.

Little survives of early Middle English literature because a trend had been established for such works to be written in French, which would appeal to the upper echelons of society. However, despite this, the majority of literary works in this period were still written in Latin, notably Geoffrey of Monmouth’s History of the Kings of Britain which popularised the tales of King Arthur.

Spoken Languages in England

With respect to the spoken word, the ordinary people naturally spoke in the vernacular which gradually moved from Old to Middle English. Latin was used in the fields of the Church, justice, administration and education, while royalty and people at the top of society spoke Anglo-Norman French. It is thought that Richard the Lionheart, who spent so little time in England, may not have spoken English at all.

Only a very small number of individuals were trilingual (Latin, Anglo-Norman French and English), thus resulting in the need for interpreters and translators. For example, the 1106 inquiry into the rights and privileges of the Church of York was led by five royal justices, all of French birth or ancestry. A jury of twelve local wisemen were called to make a true statement as to the Church’s customs. Ansketel of Bulmer, reeve of the North Riding, acted as the interpreter at the inquest. Similarly, the abbots of Ramsey had an interpreter in their entourage during the first half of the 12th century.

Useful glossaries of terms were produced to help those who were not multilingual, a sort of very rudimentary early French-English dictionary, one might say.

Middle English (1150-1470)

Early Middle English was based on Old English with additions from Old Norse and Anglo-Norman French, along with some Latin-derived words.

This was followed by Late Middle English (c. 1350-1470). Chaucer’s Canterbury Tales was written in Middle English in the late 14th century, and it was during this period that Chancery Standard English (c. 1430) began to be used in administrative documents, gradually replacing Anglo-Norman French.

Early Modern English (up to 1700)

Early Modern English began to make an appearance around the time that Caxton’s printing press appeared in the 1470s. Shakespeare’s works and the King James Bible were both written in Early Modern English.

Various dialects had been in existence across the country: Northern, Midlands (East and West), Southern and Kentish. London / East Midlands won out due to considerations of political power, trade and royal administration, while the printing press was also a factor in helping to standardise the language.

Modern English (1700 – the present day)

Modern English was mostly in place by 1700. The difference between Middle English and Modern English mainly centres on pronunciation, grammar, spelling, and vocabulary. A very brief summary of Modern English includes:

- 18th century – grammar stabilises and spelling is gradually standardised, both aided by the arrival of the dictionary, notably Doctor Johnson’s

- 19th century – significant increase in vocabulary, principally due to the advent of the Industrial Revolution and the borrowing of words from other parts of the British Empire. Examples of the latter include bungalow (Hindi), ketchup (China) and toboggan (Canada)

- 20th century – English becomes a global language, largely due to the influence of American English

- 21st century – the internet accelerates language change, which includes rapid slang cycles and more informality in writing.

Odds and Sods

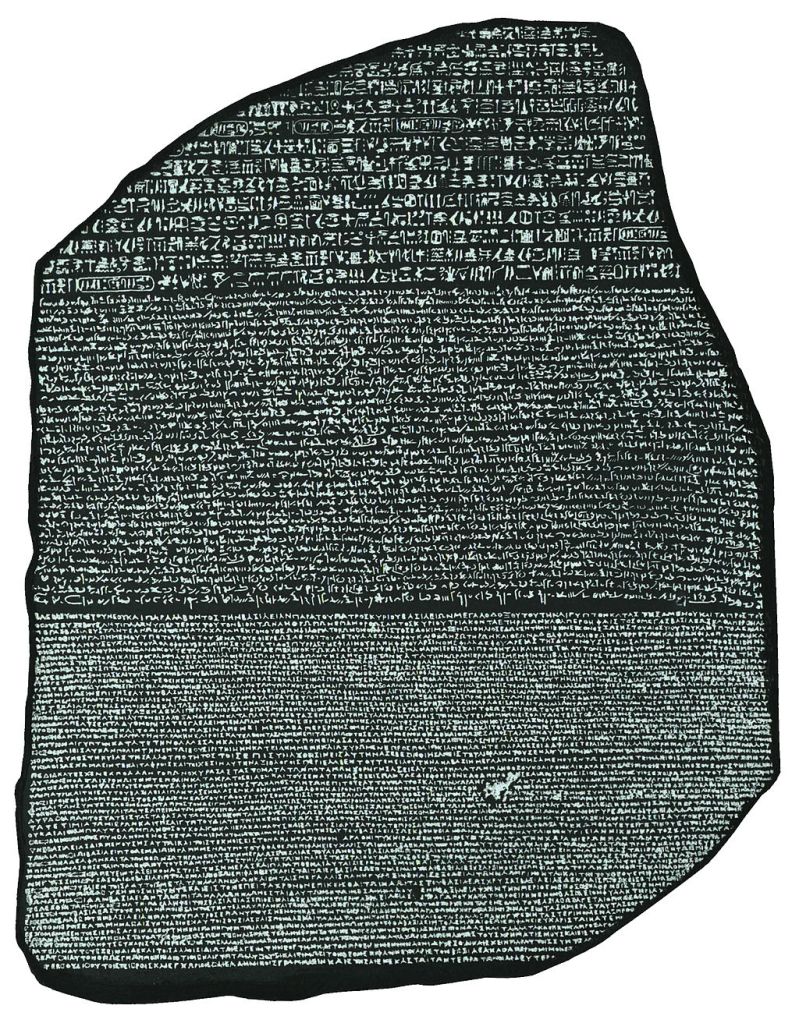

The Rosetta Stone

The Rosetta Stone, which is kept in the British Museum, dates back to 196 BCE and features the same decree, written in Ancient Greek, Egyptian hieroglyphs and the demotic script. Alexander the Great had conquered Egypt in 332 BCE. Subsequent rulers, the Ptolemies, were of Greek origin, hence the Ancient Greek. The hieroglyphs, used in religious writing, were for the benefit of the priests, while the demotic script was for the ordinary man and woman. The Ancient Greek provided the key in the efforts to deciphering the Egyptian scripts.

The stone was found near the town of Rashid (Rosetta) in the Nile Delta in July 1799 by French army officer Pierre-François Bouchard during the French invasion of Egypt.

Writing Tools

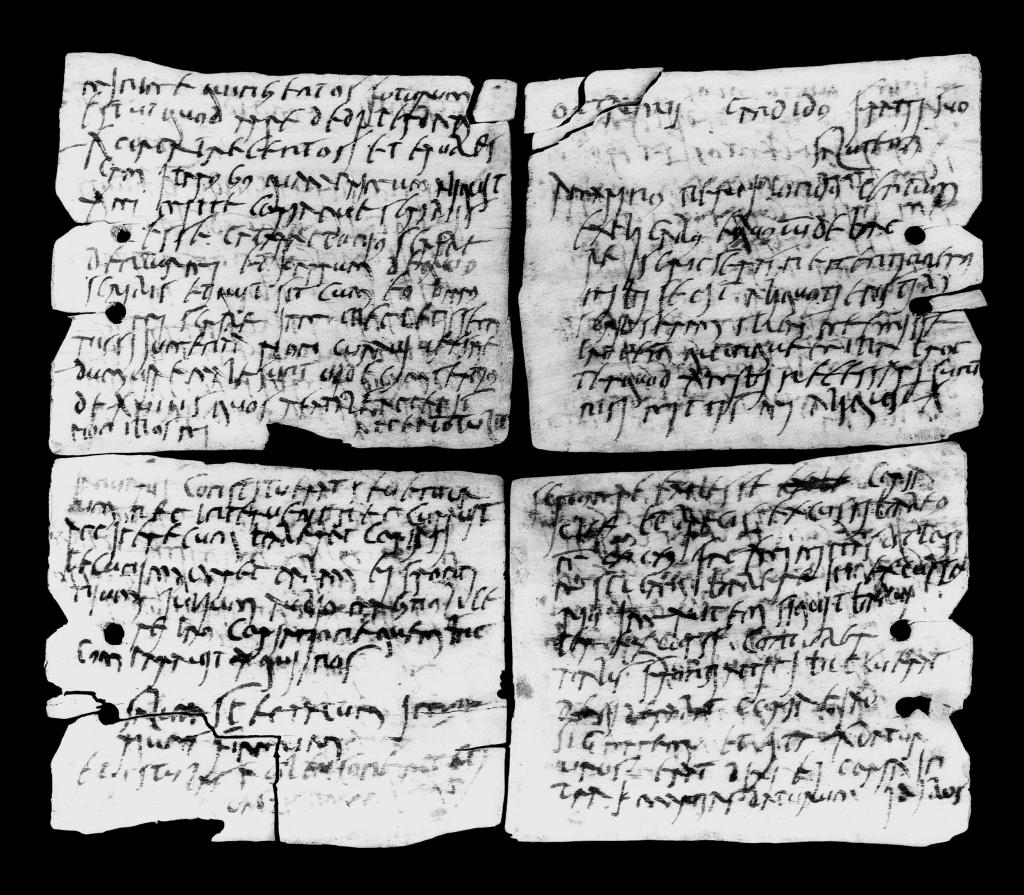

The Sumerians typically used a reed stylus with a flat triangular end to make wedge-shaped impressions on clay tablets. Temporary items would be sun-dried, while permanent documents would be fired.

The Ancient Egyptians used reed pens and charcoal-based inks to write on papyrus paper which was made by pressing papyrus reed stems together.

The Romans used a stylus on wax tablets for temporary, everyday use. They were typically reusable. Note that metal and wooden styli had appeared by this time. Parchment and eventually vellum would be used for permanent documents, using inks made with oak galls and iron salts, along with a binding agent such as gum arabic.

Parchment was made from animal skins, while vellum was only made from calf skin and was a superior product.

Quill pens, mostly using feathers from geese or swans, arrived in Europe around the sixth century CE, and by the 8th century they were commonly used to produce manuscripts. Inks continued to be based on oak galls, iron salts and gum arabic.

Paper had been invented in China. Cai Lun standardised the process in 105 CE although paper had been produced for a couple of hundred years before him. His process comprised the use of mulberry bark, hemp, rag and fishing nets pulped, formed on a screen and then dried. The process subsequently came via the Arab world (8th century CE) to Spain in the 12th century. Paper was initially imported into England from Europe around 1300 CE, but the first paper mill was not established in this country until near the end of the 15th century.

The printing press was invented by Johannes Gutenberg c. 1440, and brought to England by Thomas Caxton in 1476. It required a thick oil-based ink, made with linseed oil or walnut oil with the possible addition of resins or varnishes to improve adhesion.

Finally, it was to be around 1800 CE before metal nibs began to replace quill pens.

Sources of English Vocabulary

The following table shows estimates of the sources of the modern English vocabulary. Information from Chatgpt 5.2.

| Source | % of English Vocabulary |

| Old English | 25–30% |

| Old Norse | 4–5% |

| Germanic total (OE + Norse) | ≈ 30–35% |

| French | 25–30% |

| Latin (direct only) | 10–15% |

| Latin (ultimate origin, incl. French) | 50–60% |

| Celtic | < 1% |

Ogham Script

It is an Irish script which was used between the 4th and 9th centuries CE. There is significant debate as to the influences which produced it, and the reasons for its creation. One theory has it that it was a cryptic alphabet which would be difficult for enemies, or potential enemies, to read.

There are roughly 400 surviving orthodox inscriptions on stone monuments throughout Ireland and western Britain, the bulk of which can be found in Munster.

Bibliography and Further Reading

History Of Language

- A History of Language by Steven Roger Fischer (ebook)

- History of Language – History World

- Origin of Language – Wikipedia

- A brief history of the English Language – oxfordinternationalenglish.com

- History of Language – us.archive.org

- History of English – Wikipedia

- English language – britannica.com

- A history of the English Language – sequentialnarratives.wordpress.com

- Our Language Roots: A Journey Through Historical Linguistics – medium.com

- Language family – Wikipedia

- Indo European languages – Wikipedia

History Of Writing

- A History of Writing by Stephen Roger Fischer (ebook)

- History of writing – Wikipedia

- The evolution of writing – sites.utexas.edu

- History of writing systems – britannica.com

- The origins of writing – metmuseum.org

- Writing system – Wikipedia

- History of Writing – History World

- Bulla (seal) – Wikipedia

- History of paper

- some use of Chatgpt 5.2

Acknowledgements

I thank Janet who proof-reads all my stuff, as well as giving me useful feedback on areas that I have not covered.

All images have been found on the Internet. The captions are links to the creators. Please contact me if you consider that I have infringed any copyright.

All errors in this document are mine.

Version History

Version 0.1 – February 2026 – very drafty

Version 0.2 – February 2026 – slightly less drafty

Version 0.3 – February 2026 – incorporated JEK’s comments

Version 1.0 – February 11th, 2026.