I hope that this potted history is suitable reading for those who want more than just a simple one or two page overview, but who may be put off by full-blown books, scholarly works that are principally aimed at students and historians rather than general readers. The aim is to provide a modest piece which is both informative and readable.

After discussion of the Greeks and the Romans, this potted history concentrates primarily on British theatre.

Fill in and submit the form on the Contact Me page if you have any questions or feedback.

Contents

- Introduction

- Before Greek Tragedy

- Greek Tragedy and Comedy

- The Romans

- The Dark Ages

- Church Liturgy, Folk Plays and Pageants

- Renaissance Theatre

- Commedia dell’arte

- Elizabethan Theatre

- The Restoration

- Restoration Comedy

- Semi-Opera and Ballad Opera

- Actors and Actor-Managers

- Melodrama and Romanticism

- Pantomime

- Theatres

- Directing

- Realism and Naturalism

- Repertory Theatre

- The Stage Society

- Musical Theatre

- Political Theatre

- The Theatre of the Absurd (1940 – 1960)

- Kitchen Sink Drama

- National Theatre

- Royal Shakespeare Company

- Fringe Festivals and Theatres

- Alternative Theatre

- Theatre in Education and in Prison

- Visual and Physical Theatre and the Use of Technology

- Immersive Theatre

- Delivery Outside The Theatre

- Odds and Sods

- Theatre and the Law

- Music Halls

- Variety Theatres

- Scenery

- Stage Mechanics

- RADA and Equity

- The Arts Council

- Access

- Beginnings of Oriental Theatre

- Beginnings of American Theatre

- Bibliography & Further Reading

- Acknowledgements

- Version History

Dates. Please note that BCE (Before the Common Era) and CE (Common Era) are used in this article, as opposed to BC and AD.

Introduction

It is commonly accepted that drama began in 534 BCE with the Greeks, and for the next 300 years they gave us first tragedy and then comedy.

The Roman civilisation which followed generally adopted Greek culture, thus helping to spread theatre and other art forms as their empire expanded. Unfortunately, its eventual collapse in the 5th century CE led to the Dark Ages, dark for theatre and dark for European civilisation in general.

Kick-starting theatre again proved to be a very slow process, initially returning to the time before the Greeks when it had been partly based on rituals. It appeared to be the Church and its liturgies which was a primary driver for its regrowth, coupled with some pagan themes.

The great leap forward began with the Italian Renaissance around the 15th century, notable for the printing of the classic texts. This had little effect in England at the time, where they had to wait for Elizabethan theatre and the arrival of Shakespeare to experience a great awakening.

Unfortunately, the brakes were reapplied when the Puritans banned theatre in 1642 during the English Civil War, although it proved to be a temporary setback, as Charles II allowed it after he was established as sovereign in 1660. However, the Law, with its varying degrees of censorship, was now to be a constant theme (or should that be irritant?), right through to 1968.

In England, the 18th century was probably more noted for the arrival of the middle-class audience and the building of theatres than it was for the work of its playwrights. By the end of the century, melodrama had become the most popular form of theatre, a position which it held right through to the early 20th century.

It may possibly be said that the first strands of modern theatre began with embryonic actor-managers such as David Garrick in the 18th century. However, it is more typically considered to have arrived in the late 19th century with naturalist and realist playwrights such as Ibsen, Strindberg and Chekhov, along with the arrival of theatre directors.

The 20th century saw a clutch of new movements such as Political Theatre, Epic Theatre, Theatre of the Absurd and Alternative Theatre, while the 1980s saw the arrival of Visual and Physical Theatre with an increasing use of technology, leading to what some may call “Total Theatre”.

At the time of writing, the arrival of Covid has been the driver for the introduction of Digital Theatre and the ability to deliver productions to cinemas, art centres and home users.

Before Greek Tragedy

Historians inevitably spend time researching the antecedents to arts, sports, leisure activities, or whatever the subject matter might be, but the frequent lack of sufficiently solid evidence inevitably leads to varying degrees of speculation. Theatre is no different.

It is generally agreed that the Greeks introduced drama in 534 BCE, but where did it come from? I suggest that there are two main sources: rituals and storytelling. The Greeks would also have been helped through their access to the cultures of neighbouring civilisations that came about after the establishment of Greek colonies around the Mediterranean during the second millennium BCE.

Rituals go back as far as human beings do. Man has always seen the need to ensure that life is good and bountiful by staying on the right side of elements, such as the sea, rivers, sky, sun, weather and nature. Ritual ceremonies to honour the elements might be private, e.g. in a temple, or in public, possibly in the form of processions or festivals.

Storytelling can be visual, oral or written. Pictorial tales go all the way back to the Upper Palaeolithic cave paintings (30-40 thousand years ago); oral tales have existed as long as human language, probably commencing as simple chants before moving on gradually to epic poetry (long narratives); while the earliest known written epic is Gilgamesh, penned in the Sumerian language in Mesopotamia in the second millennium BCE. Coming much closer to the birth of drama, Homer’s Iliad and Odyssey date to the late 8th or early 7th century BCE.

In Ancient Egypt, the popular myth of Osiris, primeval king and God, gave rise to public performances long before Ancient Greece. He was killed by his brother Set, but was briefly brought back to life by Isis, his wife, allowing him to father Horus who subsequently fought with Set for the throne and ultimately triumphed. There was no dialogue in these performances.

Archilochus, a Greek lyric poet of the 7th century BCE, is thought to have been the earliest known composer of a dithyramb, a hymn which was sung and danced in honour of the god Dionysius. In Athens it was performed by a chorus of up to 50 men or boys. The City Dionysia, a festival held in honour of Dionysius, included a dithyrambic contest.

Greek Tragedy and Comedy

It is stated that in 534 BCE Thespis came out from the chorus and spoke, resulting in what is recognised as the first performance of tragedy. It is from Thespis that we get the word “thespian.”

A contest among playwrights for the best tragedies subsequently ensued near the end of the 6th century BCE, although the exact date is unclear. Three playwrights were each requested to put on three tragedies. A satyr play was added to the tragedies several years later. Thought to have been developed by Pratinas, this was a short piece which made fun of the plight of a tragedy’s characters. The satyrs were half human / half goat and resided in the chorus.

Although there were ultimately a significant number of tragedic playwrights, only three are well known to us: Aeschylus (c.525 – 456 BCE), Sophocles (c. 497 – 406 BCE) and Euripides (c. 480 – 406 BCE). Only a modest number of their works survive: 6, 7 and 18 respectively. In addition, Cyclops by Euripides is the only satyr play to survive.

There was only one actor initially, using masks to portray the different characters. Aeschylus, often called the father of tragedy, increased the number to two, and Sophocles subsequently added a third. Aeschylus also reduced the size of the chorus from 50 down to 12, but Sophocles and Euripides raised it back up to 15.

The generation after Sophocles and Euripides featured Aristophanes (c. 446 – 386 BCE), a comic playwright and poet. His works were highly satirical, called Old Comedy, but only 11 of his plays survive, around a quarter of his total output. New Comedy (comedy of manners) followed a century or more later, one of its most noted exponents being Menander (c. 342 – 290 BCE). Unfortunately, none of his works have endured.

The Greek theatre consisted of: orchestron – the performance space; the skene – a hut or tent at the back which could be used for actor changes or as a hidden stage; and theatron – the audience space, cut into the hillside, probably only populated by free males. Theatres spread, including permanent theatres in Corinth and Syracuse in the 5th century BCE, while travelling companies with temporary wooden stages also came into existence.

The Romans

The extent of Greek colonies around the Mediterranean, and the fact that the Greek language had become the lingua franca, made the adoption of Greek culture a pragmatic choice for the expanding Roman Republic. This included theatre.

The first dramatic play in Latin was written around 240 BCE by Livius Andronicus who lived in a Greek colony in southern Italy. He subsequently became a translator of Greek works into Latin, as well as penning his own material. He was followed by Plautus and Terence who were both in the New Comedy camp (after Menander). Two points are noteworthy from Roman times: female performers emerged; and painted scenery (periaktoi) first appeared.

With the advent of the Roman Empire in 27 BCE when Augustus became emperor, interest in drama tended to decline in favour of more general entertainment, such as could be seen at the Colosseum and other venues. Mime (usually lewd) became a popular art form, as did Pantomime. This is not to be confused with modern-day Pantomime; it was a non-speaking performance of dramatic scenes that was performed by a solo dancer. Arguably, Seneca (c. 4 BCE – 65 CE) was the only dramatist of any note during this period.

The Dark Ages

The collapse of the Western Roman Empire in the 5th century CE left the remnants of civilisation, including theatre, in the Eastern half of the empire, based in Constantinople, subsequently known as the Byzantine Empire. Importantly, many of the classic Greek texts were preserved by the Byzantines, while the Suda, their 10th century encyclopaedia, has provided us with much contemporary information on Greek theatre.

The lack of any political or cultural centre in the West up until the 9th century CE makes it difficult for historians to assess the state of theatre. It seems probable that it was largely limited to small nomadic bands of players performing lewd material, along with local pagan rituals.

The first signs of any rebirth appeared to come with Hrotsvitha, a 10th century Saxon canoness, female dramatist and poet, who wrote six short plays. However, her works mostly laid undiscovered until the start of the 16th century. Something of a dead cat bounce?

Church Liturgy, Folk Plays and Pageants

Small theatrical pieces began to be added to the Church liturgy from around the 10th century. Mary visiting Christ’s tomb and encountering an angel (during the Easter Mass) and the Nativity scene at Christmas are examples.

Eventually, mystery cycles with religious themes appeared . There were up to 50 short plays that covered the period from the Creation through to the Last Judgement. From the 14th century, processions, often organised by trade guilds in larger towns, included pageant wagons which would stop at predetermined points, and each give their short performance of one or more of these plays.

There were also miracle plays which dealt with the lives of saints. They could be factual, but were often fictitious, leading pope Innocent III to forbid clergy from taking part in them in 1210. They were eventually banned in England during the reign of Henry VIII.

Morality plays appeared around the 14th century, although Hildegard of Bingen’s Ordo Virtutum (Order of the Virtues) actually dates back to 1151. Possibly the appearance of the Black Death in the 14th century was one of the drivers behind the arrival of this type of play, which dealt with “the temptation, fall and redemption of the hero”. Everyman, which probably started life in the Netherlands and became very popular across Europe, is particularly noted. It deals with death and the fate of the human soul.

Folk plays and pageants began to be mentioned from the 15th century onwards, although many were almost certainly based on older pagan traditions. Examples include: Plough Monday, Wild Man of the Woods, Morris Dance, Sword Dance and Mummers’ plays.

Interludes appeared in the 15th and 16th centuries. They were short simple farces or dramatic sketches which were performed by villagers. They subsequently became known as pieces that were performed between two more serious plays.

Renaissance Theatre

Two factors contributed towards the revival of theatre during the Renaissance period: the end of the Byzantine Empire in 1453 when the Turks captured Constantinople, leading to Greek scholars moving to Italy, bringing the classical texts with them; and the arrival of the printing press in the 1430s, which allowed faster distribution of these texts.

Commedia dell’arte

Italy was the centre of the Renaissance, although new ideas about theatre were very few when compared with the huge strides that were being made in other art forms. One exception was Commedia dell’arte which appeared around the middle of the 16th century. Their works were satirical, based on medieval jongleurs and morality plays, and they made use of stock characters such as Pantalone, the miserly Venetian merchant, and Harlequin, his mischievous servant from Bergamo. Apart from key points in the plot and entrance / exits, performers were expected to improvise. This form of theatre came to inspire the likes of Moliere and Shakespeare.

Elizabethan Theatre

Renaissance style and ideas were slow to take any hold in England, and it was arguably to be the Elizabethan period before it really hit its stride in the area of literature. Theatre began to come into particular prominence when Robert Dudley, Earl of Leicester, became the patron of the first major theatrical company, which was active from the 1560s through to the 1580s. The Vagabonds Act (1572) made life difficult for travelling players, as they could be classed as vagrants. A royal patent of 1574 fortunately recognised Leicester’s Men as legitimate travelling players.

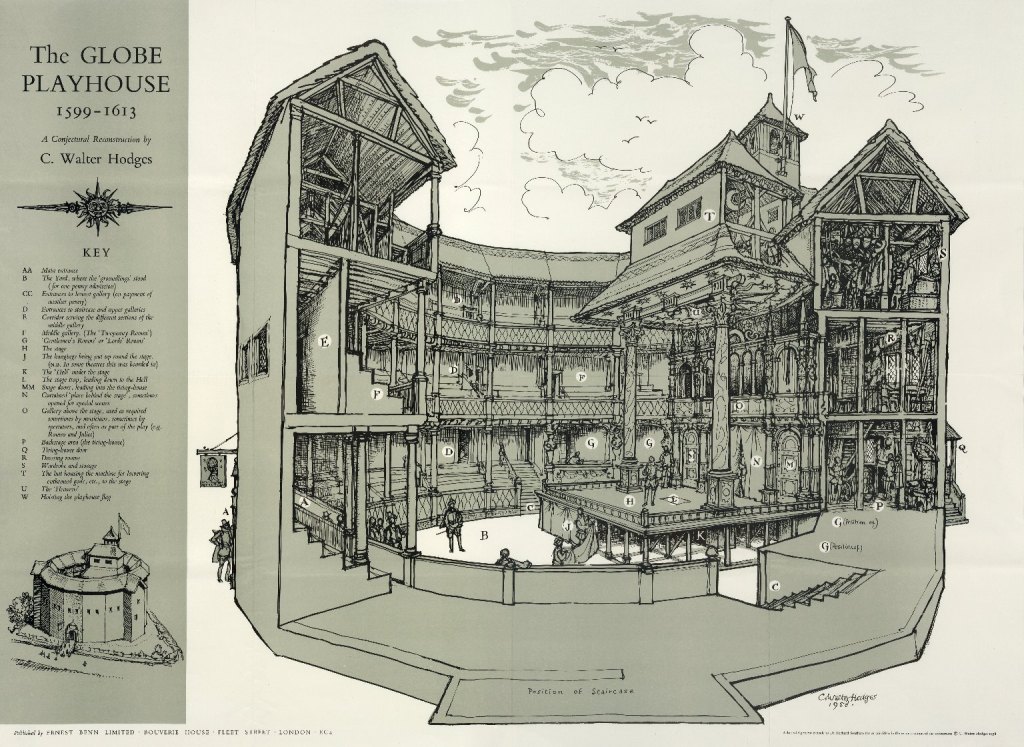

Unsurprisingly, it was courtiers, gentlemen and law students who helped to make London a centre for commercial theatre. James Burbage, actor and leader of Leicester’s Men, built the first permanent playhouse, a wooden structure called the Theatre, in Finsbury Fields in 1576. It was followed by the Rose Theatre (1587) in the Clink Liberty, the Swan Theatre in Southwark (1595), the Blackfriars Theatre (1597) and the Fortune (1600) which was built by Philip Henslowe near to the present-day Barbican. Burbage’s sons dismantled the Theatre when its lease expired and rebuilt it in the Clink Liberty in 1599, renaming it the Globe, near to the site of the modern replica which can be found alongside the Thames.

Leicester’s Men petered out after Robert Dudley’s death in 1588, and it was succeeded by two dominant companies: the Chamberlain’s Men (which included Burbage and Shakespeare); and the Admiral’s Men (Henslowe and Alleyn). In the early 1600s, James I became an enthusiastic patron, and this led to the Chamberlain’s Men being renamed the King’s Men.

Permanent companies with regular theatregoers required a steady supply of new plays, a need which was met by Christopher Marlowe and Thomas Kyd in the 1580s, followed from the 1590s by the likes of William Shakespeare, who wrote 38 plays, and Ben Jonson. Playwrights provide examples of individuals who were drawn to London by the opportunities that it offered. Shakespeare famously hailed from Stratford-upon-Avon, while Marlowe, who was born in Canterbury, is one of the many students from the universities of Oxford and Cambridge who found careers in London.

Who went to the theatre? Performances typically ran from 2pm to 5pm in the afternoons, meaning that members of the audience needed time during the day to attend. Visits to the theatre by a journeyman might inevitably be less regular. Prostitutes were attracted to the theatre, albeit to meet new clients.

The Restoration

Theatre was banned in 1642 during the English Civil War by the Puritans, although music and opera continued. May Day and Christmas Celebrations, both seen as pagan festivals, were abolished at the same time.

Charles II had become interested in the theatre while he was exiled in France during the Interregnum. After the Restoration of the Monarchy in 1660, he issued letters patent in 1662 to Thomas Killigrew and William Davenant, allowing them to form companies that could perform serious drama. Known as the Duke’s Men and the King’s Men, the main venues for their performances were the Theatre Royal in Drury Lane (founded 1663), the Duke’s Theatre in Dorset Garden (1671), the Theatre Royal, Haymarket (1720) and the Royal Opera House (1732).

As described in Theatre and the Law, only patented theatres were allowed to perform serious drama. Other venues could host music, comedy, circus et cetera, known collectively as popular culture. Sadler’s Wells (1683) was one such venue in London, followed by other purpose-built buildings in Shoreditch and Whitechapel. In addition, theatre booths were to be found in short summer fairs, including: May Fair near Piccadilly, Southwark Fair and Bartholomew Fair in Smithfield.

Other key events in this period saw the recognition of women as playwrights, notably Aphra Behn; and as actors, including Mary Betterton, Margaret Hughes, Elizabeth Barry and Nell Gwyn. Actors had only previously been males.

Restoration Comedy

The Restoration period is arguably best known for the comedies of the late 17th century which were full of witty dialogues, complex plots and sexual innuendo. They include William Wycherley’s The Country Wife (1675), Aphra Behn’s The Rover (1677) and George Farquhar’s The Recruiting Officer (1706).

Semi-Opera and Ballad Opera

French and Italian opera did not appear to appeal to the English, leading to Purcell developing the semi-opera in the late 17th century, a mixture of song and spoken dialogue. His most famous work is The Fairy Queen, based on Shakespeare’s A Midsummer Night’s Dream.

Ballad Opera was established in the early 18th century. It was a satirical play, interspersed with traditional or operatic songs, John Gay’s The Beggar’s Opera being the most famous. Prime Minister Walpole did not like political satire, leading to the censorship elements in the 1737 Licensing Act.

Actors and Actor-Managers

The 18th century saw the Age of Enlightenment and significant economic growth, leading to the rise of the middle-class audience. For the theatre in general, it was perhaps a period of transition, with the main emphasis being on changes to the style of acting.

David Garrick was at the Theatre Royal, Drury Lane from 1742 to 1776. He was an actor, producer, theatre manager and playwright.

“Garrick changed the whole style of acting. He rejected the fashion for declamation, where actors would strike a pose and speak their lines formally, and instead preferred a more easy, natural manner of speech and movement. The effect was a more subtle, less mannered style of acting and a move towards realism” – The Story of Theatre (V & A Museum)

Edmund Kean was the most notable Shakespearean actor of the following generation, performing in New York and Paris, as well as Drury Lane, in the early 19th century.

Actor-managers subsequently became popular, including: Charles Kean (the son of Edmund), Henry Irving and Herbert Beerbohm Tree who all tended to perform Shakespeare. Eliza Vestris, Sarah Lane and Madge Kendal were female actor-managers in the 19th century.

Ellen Terry was the greatest female actor of the late 19th and early 20th century. She joined Irving at the Lyceum Theatre where her roles included Portia in The Merchant of Venice and Beatrice in Much Ado About Nothing.

Melodrama and Romanticism

Melodrama was popularised in France in the aftermath of the French Revolution. It quickly spread to other countries, including England where it remained popular right through the 19th century and into the early 20th century. The format of stock characters (villain, wronged maiden and “over the top” hero), coupled with short scenes and musical accompaniment, plus visually strong scenery, were all tailor-made for non-patented theatres.

The Romantic movement, which dealt with emotions, began in the late 18th century and flourished until the middle of the 19th century. In England, it was primarily the domain of poets and novelists such as Walter Scott and Mary Shelley. Abroad, Goethe and Schiller were among the renowned playwrights of this genre.

Pantomime

Pantomime began in England in the 18th century, using Commedia dell’arte’s Harlequinade characters. It was initially mimed and contained much slapstick material, with the initial elements of speech, it is claimed, being introduced by David Garrick.

Pantomime proved so popular that Garrick sought other tales, rather than just relying on Harlequinade-based productions. It was after the monopoly of the patent theatres in London was broken in 1843 and speech was allowed that fairy tales and fables began to form the basis of productions with lavish stage sets that we would recognise today. By the late 19th century, it had become traditional that Pantomime runs would start on Boxing Day.

Theatres

Lighting was limited to the use of candles and oil lamps in the 18th century. For example, footlights were often open flame oil lamps, to which tin troughs were later added to reflect the light back onto the stage and to hide the lights from the audience. Gaslight gradually replaced candles and lamps, starting in the 1820s, followed by the introduction of the electric light from 1881 when it was first deployed in the Savoy Theatre.

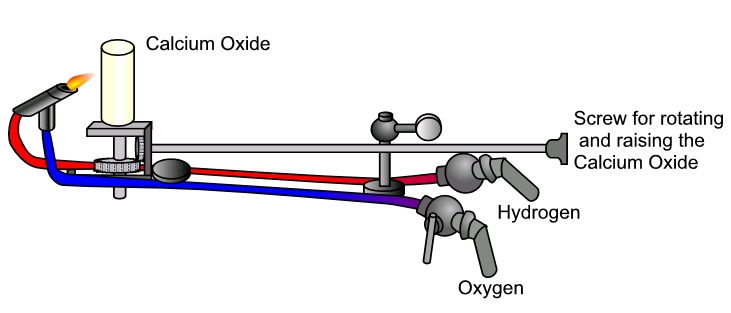

First used in 1836, limelight was an intense illumination produced by a flame fed by hydrogen and oxygen, which was directed at a container of quicklime. It was replaced by the electric carbon arc lamp spotlight in the late 19th century, that had first been used in Paris in the 1840s.

By the 1880s, theatre architecture had evolved, bringing: a semi-circular or horseshoe-shaped auditorium with classes (boxes, stalls, circle); a richly framed proscenium arch; different refreshment areas and exits / entrances.

It was around this period that the West End theatre district in London began to expand, including the arrival of the Vaudeville (1870), the Criterion (1874), the Savoy (1881) and the Comedy Theatre (1881).

Directing

From the Renaissance up to the 19th century, directing, such as it was, was usually the responsibility of the actor-manager or the senior actor in a troupe. It is thought that modern directing began with the Duke of Saxe-Meiningen’s Ensemble in the 1860s, brought about by their development of theatrical realism, which it called Gesamtkunstwerk, or “total work of art.”

It influenced Ibsen and Stanislavski, the latter who introduced his system of acting in the early 20th century, that cultivated the art of experience by the actor, as opposed to representation. It was not much used in England until the 1960s when Joan Littlewood and Michael Redgrave became advocates of the approach.

Realism and Naturalism

“Realism and naturalism are two separate, but closely linked, literary movements that began in the 19th century. Realism depicts characters and settings as they would actually have existed, while naturalism, which followed on from Romanticism, concentrates on the biological, social and economic aspects. Both seek to represent real life.” – Realism and Naturalism in Literature – Twinkl Teaching Wiki

They were both a reaction to the Romantic movement which adopted a melodramatic style. Dickens and Ibsen are classed as realists, while Zola and Strindberg are naturalists.

Censorship affected both realist and naturalist works. For example, early adaptations altered A Doll’s House (1879) to give it a happy ending in order that it could get past the local censor .. much to Ibsen’s annoyance; while Strindberg’s Miss Julie (1888) could not be performed in Scandinavia until 1905.

Chekhov is regarded as one of the influential figures in the birth of modern theatre, alongside Ibsen and Strindberg. He is noted for his “theatre of mood” where thoughts might be expressed by pauses rather than words.

Repertory Theatre

The concept of repertory was that a resident company would present works from a specified repertoire. Annie Horniman, daughter of the famous tea merchant of that name, founded the first repertory theatre at the Gaiety in Manchester (1908). Glasgow (1909), Liverpool Playhouse (1911) and Birmingham (1913) followed soon afterwards. Many 20th century star names began their careers in repertory.

The Stage Society

The society was set up in 1899 to show new and experimental work to its members on Sundays. The police raided its showing of George Bernard Shaw’s You Never Can Tell, but the society successfully challenged their action on the basis that it was a private performance, and was therefore not subject to the Lord Chamberlain’s restrictions. Club Theatres subsequently proved to be a way of getting round theatre censorship, which was eventually abolished in 1968.

The society had effectively ceased to operate by the time of World War II. However, the English Stage Company, the resident company at the Royal Court Theatre, continued its aims of presenting new work.

Musical Theatre

Gilbert & Sullivan’s comic operattas of the late 19th century proved popular in both Britain and America, followed by a long period of the latter’s domination when Broadway saw the debuts of a succession of composers, including Cole Porter, the Gershwins, Rodgers & Hart and Rodgers & Hammerstein. On this side of the pond, Noel Coward was a successful playwright and composer.

From the late 1970s, long running mega-musicals, as they are sometimes known, became very popular in Britain, notably the work of Andrew Lloyd Webber.

Political Theatre

George Bernard Shaw expected the audience to think, as he put over his political and social views. He was to influence later playwrights such as Pinter. The word “shavian” means in the manner of Shaw, or his writings or ideas.

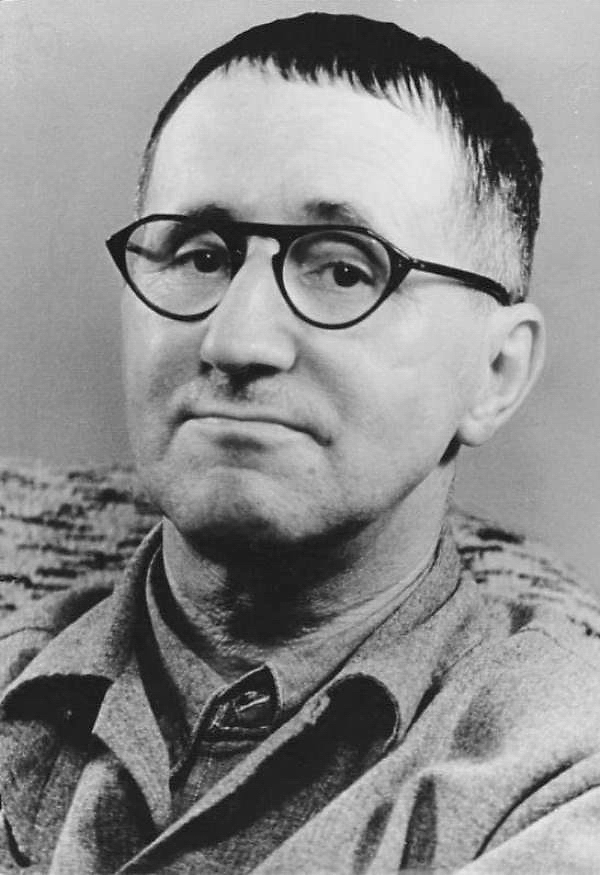

Brecht wrote plays about ideas, e.g. Mother Courage and Her Children and The Caucasian Chalk Circle. He wanted the audience to see the world as it is, rather than to suspend their beliefs. This became known as Epic Theatre.

The Theatre of the Absurd (1940 – 1960)

This movement was influenced by existential philosophy, which says that we are each responsible for creating purpose or meaning in our own lives. Beckett and Ionesco expressed what happens when human existence lacks purpose or meaning and communication breaks down, Waiting for Godot and Rhinoceros being examples.

Kitchen Sink Drama

This genre sprang into life in the late 1950s in the theatre, films, and on television. It’s aim was to describe gritty life in the North of England and in the Midlands, getting away from the escapism that may be found in the work of previous generations. John Osborne’s Look Back in Anger and Shelagh Delaney’s A Taste of Honey are arguably the most well-known examples.

National Theatre

The first call for a National Theatre had been published anonymously by a critic back in 1847. Periodic campaigns followed over the next hundred years, all seeking a memorial theatre to Shakespeare. In 1948, London County Council offered a site near to the Royal Festival Hall on the South Bank, and a foundation stone was laid in 1951.

The government’s claim that the country could not afford a National Theatre delayed matters until 1962 when the National Theatre Company was eventually formed. Laurence Olivier was the artistic director and its first performance took place in October 1963 at the Old Vic, which was leased until building of the new National Theatre was completed in 1976.

Royal Shakespeare Company

There have been various permanent theatres in Stratford-upon-Avon which have been dedicated to the work of Shakespeare, starting in 1827. There are currently three: the Royal Shakespeare Theatre, the Swan Theatre and The Other Place.

The Royal Shakespeare Company (RSC) was founded by Peter Hall who formally took charge in 1960. His primary objectives were: to have a permanent theatre company with a London base; and to include contemporary work as well as Shakespeare. RSC productions have been put on at various London theatres, including a permanent spell at the Barbican Centre.

Fringe Festivals and Theatres

The Edinburgh Festival, now known as the Edinburgh International Festival, was first held in 1947. It is a curated event, but eight theatre companies turned up in the city in that year, uninvited, and did their own thing. This was the beginning of the Fringe, given that name in the following year by Robert Kemp, a Scottish playwright and journalist. There are currently over 3,000 shows each year on the Edinburgh Festival Fringe. The concept of fringe festivals with uncurated shows gradually spread around the world, starting with Adelaide in 1960. See the list of Fringe Festivals in Wikipedia.

Meanwhile, fringe theatres can be: those that are sited near the main theatres, e.g. Off-West End in London; or venues that tend to be small (possibly over a pub) and specialise in new work or in novel adaptations of traditional works.

Alternative Theatre

The wave of political protests across the Western World in 1968 on various subjects, coupled with the end of stage censorship in the same year, opened the floodgates, allowing any subject to be tackled. Playwrights such as David Hare, David Edgar and Caryl Churchill appeared at this time, with their work being presented at fringe theatres by groups such as the Joint Stock Theatre, 7:84 and the People Show. The 1970s was arguably the peak period for this burst of creative energy.

Theatre in Education and in Prison

Theatre-in-Education (TiE) was started by the Belgrade Theatre in Coventry in 1965, touring local schools where they performed short pieces of theatre, and subsequently leading workshops which allowed students to explore important issues and ideas in active and creative ways. The TiE movement soon spread across the UK and abroad.

Jacki Holborough and Jenny Hicks met in prison, sharing a belief in the power of theatre to transform lives. They set up the Clean Break theatre company for women ex-prisoners in 1979, touring plays that revealed the struggles that are faced in prison. Unlock Drama, founded in 2014, is another organisation that delivers rehabilitation projects in prison and in the community.

Visual and Physical Theatre and the Use of Technology

The 1980s saw the beginnings of an emphasis on visual and physical theatre. Théâtre de Complicité (now just Complicité), founded in 1983, can be difficult to describe, except to say that it is eclectic in both the themes that it addresses and the techniques that it employs, which include story-telling, mime, physical movement, and the use of multi-media such as videos, projections and live cameras on stage.

Gecko was founded in 2001. Their style can be referred to as ‘Total Theatre’, which Lahav describes as “utilising any means possible to tell a story, including the creative deployment of puppets, props, physicality, language, music, lighting, multimedia and soundscapes to construct a complete theatrical world from these individual components. Through the ensemble’s collaboration and the audience’s engagement, each show continually evolves throughout their numerous stages of development.”

Immersive Theatre

To put it simply, this involves audience participation in the performance. Apart from Punchdrunk, which was set up in 2000, there was just the occasional example of this genre until its relatively recent popularity. Theatre productions at the Edinburgh Festival Fringe tend to have a noticeable theme each year, and in 2024 it was, at least in this punter’s eyes, immersive theatre.

Delivery Outside The Theatre

NT Live is a National Theatre initiative, started in 2009, which live-streams performances via satellite to cinemas and art centres. The Royal Shakespeare Company’s first live-streaming was in 2013, and it was followed by other theatres such as the Almeida with Nine Lessons and Carols.

The arrival of Covid and the associated lockdowns forced theatres to quickly consider how they could deliver productions to punters. The Almeida Theatre made Hymn available online, as did the Orange Tree Theatre in Richmond with Inside.

At the current time there are various theatres and organisations that offer on-demand streaming services.

All this has led to the hybrid art form which is currently known as Digital Theatre.

Odds and Sods

Theatre and the Law

1662 saw the beginning of various forms of theatre censorship which were to last for three centuries.

Patent theatre, as it was known, was initially limited to two companies in 1662, the King’s Men and the Duke’s Men. Only they were allowed to put on serious drama, the former at the Theatre Royal, Drury Lane and the latter at the Duke’s Theatre in Dorset Gardens (one of the first buildings with a proscenium arch), although it later moved to the Theatre Royal, Covent Garden (1720). These theatres were closed during the summer months when temporary theatres or fairs operated.

The Licensing Act 1737 saw the government enhancing its control of the theatre. Censorship of plays became the responsibility of the Lord Chamberlain and the office of Examiner of Plays. The act also introduced the terms legitimate and illegitimate theatre. Legitimate theatre was serious drama which was only performed at patent theatres. It was complemented by illegitimate theatre elsewhere across the country where non-serious forms of entertainment were allowed, including burlesque, music, dance, clowns, circus animals et cetera.

Additional patent theatres were gradually created during the later part of the 18th century, including: the Theatre Royal, Bath (1768), the Theatre Royal, Liverpool (1772), the Theatre Royal, Bristol (1778) and the Theatre Royal, Birmingham (1802)

Theatres Act 1843 limited the powers of the Lord Chamberlain. He could only prohibit the performance of plays where he was of the opinion that “it is fitting for the preservation of good manners, decorum or of the public peace so to do”. Local authorities were now allowed to licence theatres, thus breaking the monopoly of the patent theatres, and leading to saloon theatres which were attached to public houses and to music halls. Somewhat perversely, despite this freeing up of the marketplace, serious drama went out of fashion until the 1880s when the works of Oscar Wilde and Henrik Ibsen arrived, followed by JM Barrie, George Bernard Shaw and other playwrights from the 1890s onwards.

Theatres Act 1968 abolished stage censorship.

Music Halls

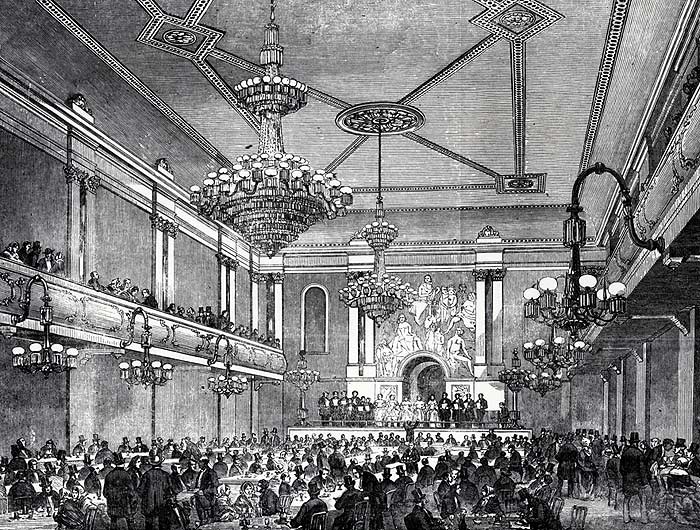

Popular entertainment in London, which had previously been found in outdoor venues such as Vauxhall Gardens, began to appear in a modest number of indoor establishments, becoming much more commonplace from the 1830s, particularly in larger taverns.

Purpose-built music halls began to appear in the 1850s, starting with the Canterbury in Lambeth in 1852, followed by Evan’s in Covent Garden (1855), Weston’s in Holborn (1857), and Wilton’s in Stepney (1858). Meanwhile, the Alhambra in Leicester Square (on the site of the current Odeon cinema), which had briefly been a circus, was converted into a music hall in the 1860s. It was estimated that there were eventually 375 establishments in the Greater London area.

The singer Marie Lloyd and Dan Leno (“the funniest man on earth”) were stars of the music hall in the late 19th and early 20th century.

However, the popularity of this form of entertainment began to wane with the arrival of talking films and variety theatre. The Canterbury was converted into a cinema.

Variety Theatres

As opposed to music halls, where the punters sat at tables, variety theatres were laid out much as drama theatres are. They appeared around the start of the 20th century, going under names such as the Empire, Hippodrome and Palace, offering a full range of variety acts. The Hackney Empire, which started life as a music hall, is one of the most well-known. Most towns had a variety theatre where many stars began their careers. The first Royal Variety Performance took place in 1912 at the Palace Theatre in London, with King George V and Queen Mary in attendance.

It was the arrival of television in the 1950s that began to adversely affect the popularity of variety theatres.

Scenery

Here are some brief notes on scenery:

- Medieval mystery plays used “mansions”, fixed scenic devices which represented the setting for a particular biblical story. They might be mounted on pageant wagons

- Theatres such as the Globe had no scenery and may resort to simple boards to indicate to the audience where the action was taking place

- The first mention of movable scenery dates from 1605 at a play in Oxford which was attended by James I

- Larger theatre companies would have resident artists to paint scenery while others might employ itinerant artists or order stock scenery from organisations who provided such services

- From the middle of the 19th century the theme of a play was to play a greater part in the choice of scenery. The realism movement demanded more accuracy, while the socioeconomic circumstances of the characters should reflect their environment.

Stage Mechanics

The Greeks introduced the first device (a crane) to show a god in the sky, while the Romans added trapdoors. Things moved on from the period of the Italian Renaissance and notably from the late 17th century in England when ever-increasingly complex machinery was used to create spectacles in dramas and pantomimes. The revolving turntable and the hydraulically elevated stages were German inventions.

Theatrical Scenery Painting and Painters

RADA and Equity

The Royal Academy of Dramatic Art was founded by Herbert Beerbohm Tree in 1904. This drama school was initially sited in the Haymarket, but it moved to its current home in Gower Street in the following year. It was granted a royal charter in 1920. George Bernard Shaw left one third of his royalties to RADA when he died in 1950.

Equity, the British trade union for the performing arts and entertainment industries, was established in 1930. It operated a closed-shop policy until they became illegal in the 1980s. However, evidence of sufficient professional paid work is still required to become a member. There were 46,000+ members in 2021.

The Arts Council

The Arts Council was formed in 1946, and by 1955 it was giving grants to 92 organisations, including the Royal Opera House and the Royal Court Theatre. 15 new theatres were built between 1958 and 1970 with the aid of public money, by which time it was supporting over 250 organisations.

In 1994 the Arts Council was replaced by the Arts Council of England, the Scottish Arts Council and the Arts Council of Wales.

Access

Assisted performances are increasingly meeting the requirements of deaf, disabled and neurodivergent people, as well as those who have requirements due to physical or mental health conditions. While the majority of theatres provide some facilities, the National Theatre arguably leads the way with:

- audio described performances for the blind or partially sighted

- sign language and captioned performances for the deaf and hard of hearing

- chilled and relaxed performances that allow for noise and movement in the auditorium and technical changes for those with sensory sensitivities

- and dementia-friendly performances.

VocalEyes was set up in 1998 with a National Lottery grant, awarded by the Arts Council of England, to help theatre venues and producers meet the needs of blind and visually impaired audiences. Its initial focus was on helping touring productions.

Beginnings of Oriental Theatre

The Rigveda is a collection of Sanskrit hymns which date back to 1500-1200 BCE. However, drama did not seem to appear in India until 200 BCE to 200 CE with the Nātyaśāstra, a treatise on the performing arts. The first dramatists around this period are considered to be Asvaghosa and Bhāsa.

In China, there are references from 1500 BCE to entertainments which included music, clowning and acrobatics. This was followed by shadow puppetry in the Han dynasty (202 BCE – 202 CE) and a form of drama that was largely musical in the Tang dynasty (618 CE – 907 CE).

Noh and Kyōgen are Japanese theatre traditions which date back to the 14th/15th century. Noh was a spiritual drama, which focused on tales with mythic significance, while Kyōgen employed farce and slapstick. Kabuki was subsequently developed in opposition to Noh theatre, which was primarily restricted to the upper classes.

Beginnings of American Theatre

Although some theatrical events had been organised by the Spanish and Native Indians long before an English colony became established, the first theatres appeared in the 18th century. It is thought that professional theatre began when Lewis Hallam arrived in Williamsburg, Virginia with his company in 1752.

The performance of plays was banned in some states during the second half of the 18th century, while playwrights and actors were generally looked down on.

Before the Civil War, performances of Shakespeare’s plays became fairly commonplace, along with melodramas which became as popular as they were in Europe, one example being Uncle Tom’s Cabin.

There was an almost wholesale ban on plays during the Civil War, but matters improved after the war with playwrights and actors gradually receiving greater public respect, and the arrival of the railway which allowed travelling companies to tour the country with less hassle.

Vaudeville and Broadway became extremely popular from the late 19th century, while serious playwrights, such as Eugene O’Neill, Tennessee Williams and Arthur Miller, eventually achieved worldwide fame in the 20th century.

Bibliography & Further Reading

The Oxford Illustrated History of the Theatre, Brown (Editor), J.R., Oxford University Press, 1995

Masks – a bit of politics and a bit of history (lazaruscorporation.co.uk)

Mask – Wikipedia

Osiris myth – Wikipedia

coas.ojsh.0201.02019k.pdf Ancient Festivals & Their Cultural Contribution to Society

Epic poetry – Wikipedia

Epic of Gilgamesh – Wikipedia

206 Classical Greek Theatre, Classical Drama and Theatre

Satyr play – Wikipedia

Festival – Wikipedia

History of theatre – Wikipedia

Chorus | Definition, History, Examples, & Facts | Britannica

Greek chorus – Wikipedia

The History of the Greek Chorus | The role of the Chorus in ‘The Oresteia’ (wordpress.com)

The story of theatre · V&A (vam.ac.uk)

Stunning Theatre History Timeline (from 2000 BCE to today) – ★ Toby Simkin ★ Broadway Entertainment

Theater | Definition, History, Styles, & Facts | Britannica

Western theater | Definition, History, Plays, Characteristics, Examples, & Facts | Britannica

Chester Mystery Plays

Morris dance – Wikipedia

Mumming play | Medieval, Folklore & Ritual | Britannica

Everyman (15th-century play) – Wikipedia

The story of pantomime · V&A (vam.ac.uk)

The Great British Music Hall – Historic UK (historic-uk.com)

Repertory theatre – Wikipedia

Repertory theatre | Acting, Performance & Improvisation | Britannica

Fringe theatre – Wikipedia

Royal Academy of Dramatic Art (RADA) | Britannica

Guildhall School of Music and Drama – Wikipedia

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Royal_National_Theatre

Royal Shakespeare Company – Wikipedia

Stanislavski’s system – Wikipedia

Theatre-in-Education (TiE) – Belgrade Theatre

About Us — Clean Break

Unlock Drama | Rehabilitation projects through theatre

About Punchdrunk : Immersive Entertainment Pioneer

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Theater_in_the_United_States

Those Variety Days By Donald Auty

Welcome to Arthur Lloyd.co.uk (history of the theatre and music halls in the UK and Ireland)

Acknowledgements

I thank Janet who proof-reads all my stuff, as well as giving me useful feedback on areas that I have not covered.

I thank the other individuals who have read the initial draft and similarly provided me with useful feedback on areas that I have not covered, but who wish to remain anonymous.

All images have been found on the Internet. The captions are links to the creators. Please contact me if you consider that I have infringed any copyright.

All errors in this document are mine.

Version History

Version 0.1 – December 21st, 2024 – Very drafty

Version 0.2 – December 23rd, 2024 – marginally less drafty

Version 0.3 – December 24th, 2024 – a bit better

Version 0.4 – December 28th, 2024 – feedback from JK

Version 0.5 – December 30th, 2024 – added National Theatre and RSC

Version 0.6 – January 3rd, 2025 – feedback from RK

Version 1.0 – January 6th, 2025.